“She was a voluptuous creature.” So said veteran San Francisco police detective Ben Bohen in 1890 when recalling Belle Cora (depicted at right), the most notorious woman of Gold Rush–era California. The beautiful and cultured Cora ran San Francisco’s preeminent bordello. Among her clients and friends were influential politicians, businessmen, lawyers and judges. But when Belle’s lover shot and killed a prominent U.S. marshal, she found herself in direct conflict with not only the city police and prosecutor but also the feared 1856 Committee of Vigilance. Despite such formidable adversaries, in the end her true nemesis proved to be another woman, a California pioneer of an entirely different cloth.

The Coras Head West

San Francisco’s Gold Rush vixen was born Arabella “Belle” Ryan in Baltimore, Md., in 1828. Belle and sister Anastasia, two years her senior, were orphaned in childhood. The Ryan girls attended grammar school, but as teens they went to work in a dressmaking shop. Detective Bohen, a few years Belle’s junior, also grew up in Baltimore and knew the Ryans. As he later explained, the sisters often delivered gowns from the shop to the “hurdy gurdy” girls in a nearby bordello. “The girls were compelled to go to and from this place frequently, and in time developed a desire to lead the free and rollicking life of the women for whom the dresses were intended, and shortly afterward commenced a career of dissipation.”

In 1848 a restless Belle boarded a steamship bound for Charleston, S.C., where she took up with a lover. Her choice of companions was poor, for he was soon killed. Belle then boarded another ship, this one bound for New Orleans. There, as Bohen recalled, “She met Charles Cora. He was a prosperous gambler and was struck by her beauty.” Twenty-year-old Belle was indeed attractive, with a round face, thick brown hair, hazel eyes, a fair complexion and a plump, well-endowed figure. She in turn fell for the dashing gambler.

Cora was a well-known figure in the card rooms of New Orleans. Born in Genoa, Italy, in 1817, he immigrated to America with his family as a boy. One of his gambler friends, J.J. Bryant, later said Charles’ parents had abandoned him in the wide-open town of Natchez, Miss. “He was an ignorant Italian boy,” Bryant said, “and had been picked up and raised by a woman who was the keeper of a house of prostitution in Natchez.” Before turning 30 Cora had plied the Mississippi River as a successful and wealthy gambler. In 1846 he drifted back downriver to settle in New Orleans, where he became noted for his success at the faro tables.

Cora stood 5 feet 7 inches and was heavyset, with hunched shoulders, dark hair and a drooping mustache that covered his mouth. Like most gamblers, he dressed immaculately, accessorizing with an embroidered vest and a top hat. He was also quarrelsome. In May 1847 Cora got into a brawl and assaulted a New Orleans police officer. Five months later he engaged in another fracas in a New Orleans dance hall and landed in jail. A year later Cora met Belle Ryan, and from then on the pair lived together as man and wife, though they never legally married.

At the time Charles and partner Sam Davis were running a faro bank on Carondolet Street, near the French Quarter. In the spring of 1849, in a precursor of later events in San Francisco, Cora assaulted a man who’d insulted Belle. In revenge the man turned in Cora and Davis, who were arrested and charged with running an illegal gambling house. After a much-publicized hearing a judge released the pair after each paid a whopping $5,000 bail bond, roughly equivalent to $200,000 in today’s dollars.

News of the huge gold strike in California was then sweeping the globe. Resolving to join the Gold Rush, Charles and Belle boarded a gulf steamer, crossed the Isthmus of Panama, and took another steamship north to California. Fellow passenger E.L. Williams recalled that Cora and three companions started trouble aboard ship until the captain finally clapped all three in irons. Rumor had it Cora and cohorts carried on them $40,000, with which they planned to start a faro bank in San Francisco. In late December the steamer sailed through the Golden Gate.

Belle and Charles surely found ramshackle San Francisco a far cry from Baltimore or New Orleans. The harbor of the roaring boomtown was crammed with hundreds of abandoned vessels, their crews having jumped ship and left for the goldfields. Its 25,000 inhabitants were overwhelmingly young and 90 percent male. Most lived in canvas tents and rough wood-frame houses. A promising sight to the disembarking couple, however, were the dozens of saloons, gambling halls, fandango houses and bordellos.

An Incident at the Theater

In 1849 women were so scarce in San Francisco that when a member of the fairer sex strolled down the board sidewalks, crowds of lonesome, homesick miners would flock out of the saloons and gambling tents, hats in hand, just to catch a glimpse. Prostitutes accounted for much of the scant female population.

Leaving San Francisco for richer grounds, Belle and Charles took a ship bound up the Sacramento River to Marysville, gateway to the Sierra Nevada goldfields. There, in partnership with one James Y. McDuffie, they opened a gambling hall and bordello called the New World. “I remember seeing a bet of $10,000 made at poker by Charles Cora,” recalled one Forty-Niner who patronized the New World. “He won his bet.”

In 1852, flush with cash, the couple returned to San Francisco, where Belle took to using her paramour’s surname. There, at the corner of Dupont (present-day Grant Avenue) and Washington streets, in what today is Chinatown, she opened a brothel in one of the ubiquitous wood-frame houses.

As women remained scarce, men flocked to Belle Cora’s bagnio, which became the most successful of the more than 100 brothels in town. Though plain on the outside, its interior was replete with fancy furnishings and even fancier courtesans. Among the clientele were prominent merchants and political figures, including the mayor. As Belle prospered, she lavished money on Charles, which he quickly lost in the faro dens. The modish madam also tapped her newfound wealth to buy a fancy carriage, in which she enjoyed riding about town with her girls and to the theater with her husband—that is, when he was in town.

As he had on the Mississippi, Charles roamed widely, following the gambling circuit to Marysville, Sacramento and around again. On Oct. 26, 1852, he got into a quarrel with a dangerous gambler, Thomas Moore, at the El Dorado saloon in Sacramento. Both men jerked out Colt revolvers, one walking out into the street, while the other stood in the brick doorway. Customers scattered as the two opened fire. Fortunately for Cora, none of Moore’s shots found their mark. A police officer soon arrived on the scene and arrested both men. Each was released after forking over a $1,000 bond, and neither faced prosecution.

In the spring of 1855 Belle moved into a new, two-story brick building at 27 Waverly Place. By then San Francisco had greatly modernized. Replacing the tents were multistory brick buildings on streets paved with cobblestones and illuminated by gas lamps. The improvements prompted miners and merchants alike to send for their wives and families, bringing more and more respectable, middle-class women to town. The latter development brought Belle no end of trouble and scorn. At the same time Charles remained fiercely protective of her.

On the night of Nov. 15, 1855, Belle and Charles attended a play at the American Theater, with seats in the exclusive first balcony. In the row directly in front of them was William H. Richardson, 34, the U.S. marshal for northern California, accompanied by his 22-year-old wife, Lavinia, and a female friend. The Richardsons had been married for two years, and Lavinia was six months pregnant. Richardson, like many San Francisco pioneers, was a former soldier, a heavy drinker and quick to take up an insult or a quarrel. Neither he nor his wife had any idea a notorious madam was sitting directly behind them.

At intermission the lights went on, and Lavinia and her friend noticed men in the pit below leering at them and laughing. Lavinia complained to her husband, and Richardson went down to confront the offenders. The men explained they had not been looking at Lavinia, but rather at Belle Cora, just behind her. A furious Richardson stormed back to the balcony and demanded Charles and Belle leave at once. When they refused, the marshal complained to the theater manager. The latter declined to eject such wealthy patrons, so the Richardsons left in a huff.

The next evening William Richardson happened across Charles Cora in the Cosmopolitan saloon. Both had been drinking, and they exchanged angry words. Cora then announced to onlookers, “This man is going to slap my face!” Richardson replied with a grin, “I promised to slap this man’s face, and I had better do it!”

At that, their respective friends stepped in and separated the pair.

The next evening, November 17, Cora was drinking in the Blue Wing saloon on Montgomery Street. As was his custom, he carried a pair of single-shot derringers in his pockets. When he heard that a man outside was asking for him, Cora stepped through the door and found Richardson waiting on the sidewalk. The marshal was also armed, carrying a concealed derringer and a silver-sheathed bowie knife.

In conversation, the two walked to the corner of Clay and Leidesdorff streets, where Cora suddenly pushed Richardson into a doorway.

“What do you mean to do?” exclaimed Richardson. “Do you mean to shoot me?”

“No, but I want to talk to you,” declared Cora. The gambler instead seized the marshal’s collar with his left hand, then yanked out a derringer and thrust it into Richardson’s breast.

“Don’t shoot!” the marshal pleaded with his assailant. “I am unarmed!”

Cora fired once, and the bullet tore into Richardson’s chest, a mortal wound. Cora held the marshal upright for long moments, then abruptly dropped his corpse and strode up the street.

Arrested almost immediately, Cora was scarcely in jail before outraged citizens had gathered outside, calling for his lynching. Belle was overcome with anxiety, for she well knew that on the California frontier murderers were generally sentenced to death by hanging. She was determined to save her man from the noose.

Witness Tampering

At the coroner’s inquest two days later the first witness called was 35-year-old Maria Travis Knight, who, like her husband, came from a respectable, well-to-do New England family. In testimony confirmed by other eyewitnesses, Maria described the killing and swore Richardson had not been holding a weapon when shot. Her testimony was critical, as she’d been passing down the same sidewalk and was standing only steps away when the fatal shot was fired.

Belle grew frantic when Charles was indicted for murder, his trial set for Jan. 3, 1856. She sent a prominent attorney to the Knight home. Explaining that his client was overcome with grief, the lawyer beseeched Maria to meet with Belle. At first Knight refused, but when a family member appealed to her Christian sense of duty, Maria finally consented.

The next evening, guided by a confidante of Belle’s, Knight climbed a vacant lot to the rear of the notorious bordello. “A long path through a beautiful flower garden led to a door of the house, which was opened from within by two servants,” Maria recalled. “Behind the servants stood the madam, who called herself Mrs. Cora. She was smiling and cordially invited us to enter.” Forty years later Knight recalled her hostess vividly. “She was superbly attired in black silk with costly laces,” Maria wrote. “Although she possessed the grace of a highly cultured woman, I shrank from her and wanted to run, but feared to make an attempt to escape.” After 10 minutes of casual conversation, Belle poured her visibly anxious guest a glass of wine.

“You seem nervous,” Belle said sweetly, “and the wine will help you.”

But middle-class women did not socialize in brothels, and they did not drink alcohol.

“I have never tasted liquor of any kind,” Knight told Cora.

“[Belle] quietly put the glass on the tray and then sat down by me,” recalled Maria. “She talked about the weather, her health and trivial things, and then most particularly inquired after my own health.” Belle then briefly left the parlor and returned with a cup of tea, saying, “I have brewed it expressly for you.”

By then Knight was overcome with fear, suspecting both the wine and the tea were poisoned. Again she refused. After more small talk, Belle finally turned to the topic of Richardson’s death. Maria replied with the same account she’d given at the coroner’s inquest. Then Belle asked, “What did Richardson have in his hand?”

“Nothing whatever,” Maria responded. “I distinctly saw that his fingers were extended and that it would be impossible to hold anything with his hands wide open.”

Belle cross-examined Knight, trying to get her to change her story, but Maria wouldn’t budge. Seething with anger, Belle abruptly stood and loomed over her guest. “Woman, if you expect to get out of this house alive, you must say that you saw Richardson with a pistol in his hand! That is the only ground we have to save my husband’s life.”

Though terrified, Knight managed to reply in an even tone, “Madam, I did not see a pistol in Richardson’s hand, and I cannot say that I did.”

An enraged Belle rushed to the parlor door and swung it open. Two men burst through the doorway. Knight recognized one of them—Dan Aldrich, a well-known gambler. He held a steel dagger in his hand. Maria later testified that Aldrich towered over her with the knife and growled threats. “My life would be spared if I would accept $1,000 and leave the country,” she recalled the trio telling her. “I must also promise never to return.”

Frantic to escape, Maria readily agreed. Belle told her they would later reveal where the bribe money was buried. Knight then rushed from the bordello and down the long hillside to her home. As soon as she’d recovered her wits, she reported the whole affair to the prosecuting attorney. Meanwhile, Belle set out to bribe other witnesses. She also hired three of the most prominent lawyers in California, paying them $5,000 each to defend Charles.

When the trial began a few weeks later, Knight was again a key prosecution witness. Charles Cora’s lawyers produced a parade of witnesses for the defense. Several of his gambler friends from New Orleans swore he had a reputation there as a peaceable man, which was false. Few of the defense witnesses had appeared at the coroner’s inquest, yet two men in turn took the stand and claimed Richardson had had a knife in hand when shot. On cross-examination both admitted they had visited Belle at her brothel before the trial, though each insisted he’d not been bribed.

Though it was clear there had been witnesses tampering and bribery, the trial resulted in a hung jury. San Franciscans were shocked. Knight had testified not only that Richardson hadn’t had a weapon in hand, but also that Belle Cora had threatened her life and tried to bribe her. Her account was plainly true, for no respectable woman would ever admit having set foot inside a brothel. Public shock turned to outrage when evidence surfaced that Belle had also offered a bribe to at least one of the jurors. “Rejoice, ye gamblers and harlots,” wrote crusading newspaper editor James King of William in ridicule of the verdict. “Assemble in your dens of infamy tonight and let the costly wine flow freely, and let the welkin [heavens] ring with your shouts of joy!”

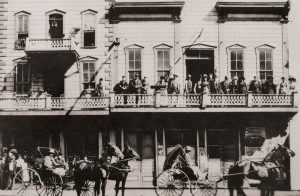

The editorial struck a chord, for the city had been under the thumb of corrupt Tammany Hall politicians from back East. The latter’s enforcers, known as “shoulder strikers,” were ruffians from the street gangs of New York. That May 14, while Cora languished in jail awaiting a new trial, a crooked politician named James P. Casey mortally wounded King, who had exposed Casey as an ex-convict from New York. In short order upward of 8,000 men, many of them veterans of the Mexican War, reorganized the city’s famed Committee of Vigilance. Seizing weapons from state militia armories, they took control of San Francisco’s government. Their headquarters, a two-story building on Sacramento Street fortified by a sandbag breastwork, was known as “Fort Gunnybags.”

On May 18 more than 1,500 vigilantes surrounded the jail and, at the point of a heavy cannon, seized Charles Cora and James Casey. Two days later, within the confines of Fort Gunnybags, the prisoners were tried by the vigilantes and sentenced to death. Belle’s money and influence were irrelevant. On the day of execution, May 22, Charles asked a Catholic priest to give him the last rites. The father refused unless he first married Belle. She promptly came to Fort Gunnybags, where the priest performed the wedding. An hour later Cora and Casey, with nooses draped around their necks, stepped onto gangplanks protruding from two second-story windows. Within moments both plunged to their deaths.

Over the next two months the vigilantes hanged two more murderers and rounded up some 40 shoulder strikers and other hard cases, placing many aboard ships bound for Central America and Hawaii. Meanwhile, Belle Cora returned heartbroken to her bagnio on Waverly Place. Perhaps to deal with her grief, Belle took opium. She soon became addicted to it and later to chloroform. In myth and popular history the madam gave up her wild life and lived quietly in San Francisco. That was hardly true. She continued to run her bordello another six years. In 1857, when a policeman tried to make an arrest in Belle’s place, one of her girls broke a bottle over the officer’s head. Two years later another of her courtesans was arrested after promenading downtown in a revealing “French square neck” dress. Several other disturbances and scandals took place at her brothel. Then, in 1862, Alexander Purple, a thug whom the vigilantes had run out of town in 1856, cut his throat in the basement of Belle’s brothel after she’d rejected his advances. He later died.

Two weeks later, on Feb. 18, 1862, Belle herself died at the bordello from the effects of the habitual abuse of chloroform. California’s most notorious woman was only 35 years old.

What became of Belle’s nemesis, Maria Knight? In 1859 she divorced her husband, months later marrying prominent sea captain Samuel J. DeWolf. Six years later, on July 30, 1865, DeWolf’s steamer, Brother Jonathan, ran aground and sank off northern California, taking with it DeWolf and most of his 244 crewmen and passengers. A year later Maria stopped by the art studio of Gideon Jacques Denny, San Francisco’s foremost marine painter, to buy an oil on canvas of Brother Jonathan, when Denny’s ex-wife walked in and spotted the pair talking. Overcome with jealousy, the woman pulled a pistol and fired as Maria fled for her life. The widow DeWolf outran the bullet and lived to age 86, dying in 1906. In later years she often regaled listeners with the story of her run-in with Charles and Belle Cora. She was the last living eyewitness to the deadly quarrel that helped ignite the nation’s largest vigilante movement.

San Francisco-based writer John Boessenecker is a special contributor to Wild West and the author of 12 books about the American West. For further reading see his book Against the Vigilantes: The Recollections of Dutch Charley Duane, as well as The Madams of San Francisco, by Curt Gentry, and History of California, by Theodore Henry Hittell.