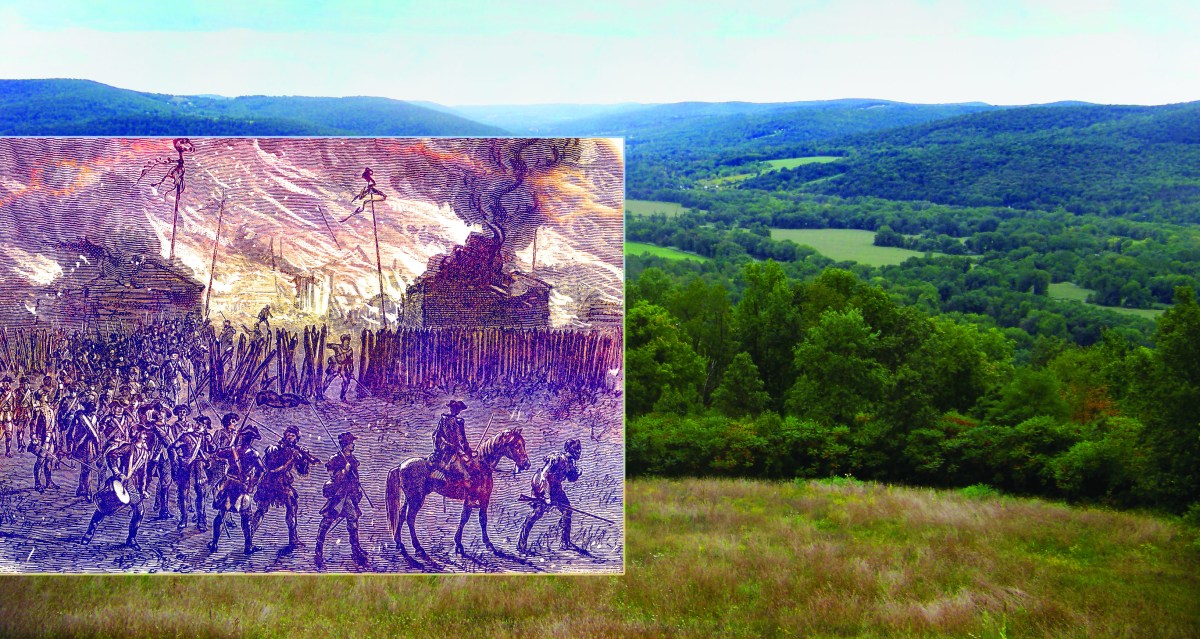

In November 1778 a mixed force of 300 Iroquois, 150 Tories and 50 British soldiers raided the farming settlement of Cherry Valley on the New York frontier. They killed 30 civilians and 16 Patriot soldiers and took 70 captives (mostly women and children). Hacking their victims to pieces with tomahawks, the American Indians left behind what one witness termed “a shocking sight my eyes never beheld before of savage and brutal barbarity.”

In the summer of 1779 George Washington sent a 4,000-man army under Maj. Gen. John Sullivan north from Pennsylvania to punish the tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy. The immediate object of the expedition, Washington instructed Sullivan, was “the total destruction and devastation of their settlements.…It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.…The country may not be merely overrun but destroyed.”

Starting north from Easton, Pa., on June 18, the column struggled across the trackless terrain. “Such cursing, cutting and digging,” Sgt. Moses Fellows journaled, “oversetting wagons, cannons and packhorses into the river, etc., is not to be seen every day.” It was well into August before the army crossed into New York.

As the troops marched north, they noticed increasing numbers of Iroquois warriors slipping through the trees around them. Brigadier General Edward Hand, whose brigade led the column, duly sent out a scouting party under Lt. Thomas Boyd. On August 29, as Boyd approached Baldwin Creek amid steep hills, the lieutenant grew wary and halted. (The site lies just north of the New York–Pennsylvania line some 5 miles southeast of present-day Elmira, the Chemung County seat, which started life in the late 1780s as the settlement of Newtown, from which the ensuing battle takes its name.)

Boyd sent a rifleman scrambling up a tree with a field glass. The man soon spotted rough fortifications along a ridge where an ambush had indeed been set by some 500 Iroquois, 200 Tories and 70-odd British rangers and soldiers under the combined leadership Col. John Butler and Joseph Brant, perpetrator of the Cherry Valley massacre.

“Their breastwork was made of pine logs,” Lt. William McKendry wrote in his journal, “covered with scrub bushes that no one might discover the same until they were quite on it. It extended near half a mile in length.”

Boyd sent a messenger to warn Hand. Advancing quickly with his brigade, the general directed artillery fire on the enemy emplacements. Realizing the jig was up, Butler sent 400 skirmishers to the creek, hoping to lure his prey closer. But Sullivan had forewarned Hand of just such a tactic, and the brigadier stayed put.

By then the rest of the column had come up. While Sullivan’s riflemen and artillery kept the enemy pinned down at the center, the commander sent a regiment to flank the enemy right and two brigades around their other flank. Two hours later the American artillery opened a fearsome bombardment, the flanking forces assaulted the ridge, and the defenders fled. Sullivan had lost 11 killed and 32 wounded. The Iroquois had lost a dozen killed and scores wounded, not counting those they managed to carry from the field. Among the Brits and Tories, five were killed, seven wounded and two captured. The army spent the next day, McKendry wrote, “in destroying the corn.”

But for an attack on a scouting party late in the expedition—an ambush in which Boyd and his sergeant were captured and later horrifically tortured and killed—the Iroquois mounted no more organized resistance to Sullivan’s column. The army continued northwest, burning American Indian settlements and destroying crops as displaced tribes fled northwest to shelter with the British at Fort Niagara on Lake Ontario. By mid-September Sullivan had reached the Genesee River just west of the Finger Lakes. With the onset of winter the column turned back toward Pennsylvania.

While much of the present-day 2,100-acre historic site is in private hands, the 372-acre Newtown Battlefield State Park, centered on Sullivan Hill, sees some 35,000 annual visitors, including campers at the park’s 18 sites and five cabins, as well as deer hunters in the fall. In 1912 state officials erected a monument, and in the 1930s Civilian Conservation Corps crews built many of the park facilities. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. Outside of more cleared land than was the case in 1779, the register notes that “the overall battlefield is otherwise little altered or impaired.” MH

This article appeared in the July 2020 issue of Military History magazine. Subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: