Iowa POWs walk nearly 300 miles in their bid to make it back to Union lines

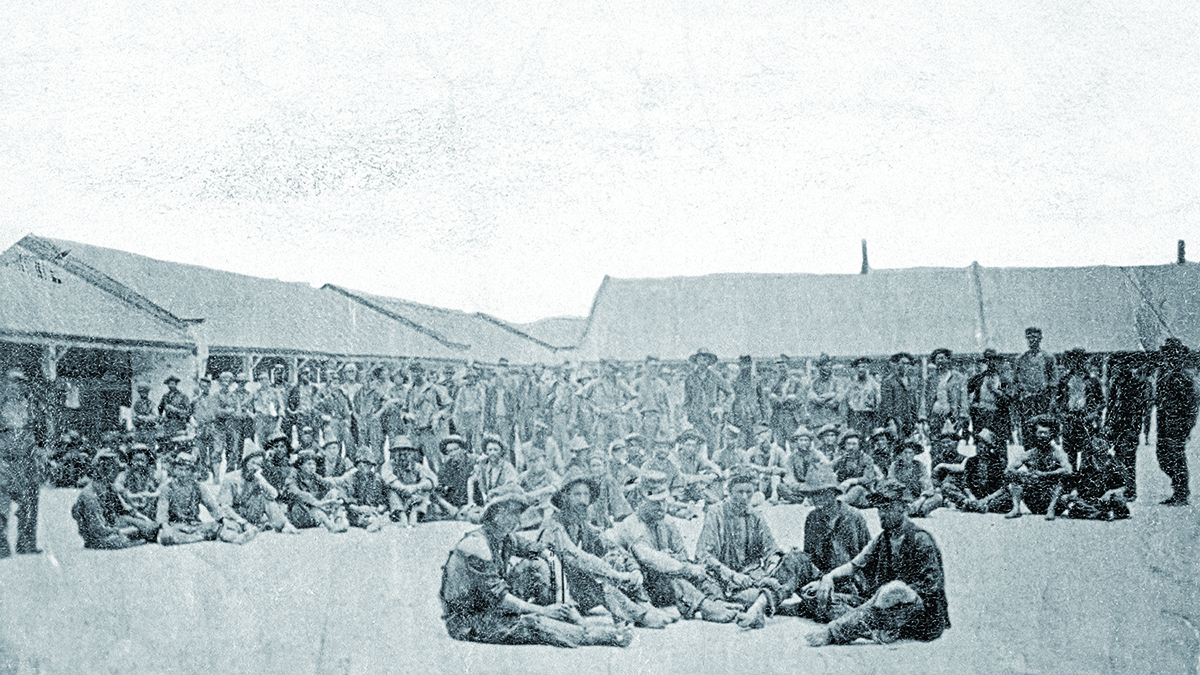

RAISED IN KEOKUK, the 19th Iowa Infantry was among several Hawkeye State regiments formed to fight for the Union in the summer of 1862. On September 4, about 1,000 soldiers and officers boarded ships and headed down the Mississippi River toward heavy fighting. Three months later, the regiment—part of Brig. Gen. Francis Herron’s 3rd Division in the Army of the Frontier—was severely bloodied at the Battle of Prairie Grove and then took part in the Siege of Vicksburg. Eventually transferred to the 13th Corps in Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ Department of the Gulf, the 19th on September 29, 1863, fought at the Battle of Stirling’s Plantation, La. In the Confederate tactical victory that day, nearly all of the Hawkeyes present, as well as roughly half the 26th Indiana Infantry, would be captured. By mid-October, the members of the 19th had been marched more than 300 miles to Tyler, Texas, and imprisoned at Camp Ford (named after legendary Texas Ranger and Civil War Confederate Colonel John S. “Rip” Ford). The Iowans were among the first of the 5,500 Union prisoners eventually sent to Camp Ford, which made it the largest Confederate prison in the Trans-Mississippi Theater. Importantly, the stockade had a clean water supply, and soon POWs had built suitable wood huts within its 4-acre expanse. Camp Ford was certainly no Andersonville. In fact, its 5.9 percent death rate was one of the lowest of the war, either North or South. But despite the tolerable conditions, J. Irvine Dungan grew tired of prison life after a few weeks and decided to attempt an escape. After the war, Dungan wrote the 19th Iowa’s official history. The following is part of that account:

November the 8th, Horatio W. Anderson, Wm. McGregor and myself, having made all the preparations for escaping that was possible, determined to delay no longer, and as the shadows of the pines grew longer and stretched far over the stockade, putting on our scantily filled haversacks and bidding the boys a hasty good-bye, we crept over the guard line and shaking from our feet the dust of the pen, shaped our course for the north star, with the intention of going to Fort Smith [Arkansas, 280 miles from Tyler, under Union control].

For ten hours we kept steadily on our course with an occasional alarm, and near morning stopped to conceal ourselves during the day. That long day came to an end at last, and at dusk we started on, coming to [the] Sabine River bottom about ten o’clock. For two hours we struggled on through vines and tangled undergrowth, until finding it impossible to proceed, we thought to lie down but could not for the dense growth of shrubs and vines; however, we cleared a sufficient space with our hatchet to lie upon till morning, and the Sabine was reached by sunrise.

The trio initially felt safe enough to travel by day, being in “wild and unsettled” country.” Coming across a small house at one point, its owner absent, they were able to supplement their food supply and procure a compass “that proved of great benefit to us afterward.”

We then walked rapidly on till midnight. Resting till near morning, we started on and about noon found three girls chopping in the woods, and asking of our whereabouts found we were not far distant from Mount Pleasant [70 miles north of Camp Ford]; being asked to go to the house for dinner we went quite willingly. When they found who we really were they told us their father and brother were “laying out” to keep out of the army. After dinner[,] going on five or six miles we saw a house at which we stopped for something to carry with us to eat.

The doorstep had hid itself away in the weeds, the well was stagnant and to the handle, idle for months, dangled a lazy rope, so rotten, the pail had broken away from it and fallen into the water. A little pale meek-eyed woman told us, pointing to a small corn cake, “that’s all we have in the house,” then added with tears in her eyes and voice “my John’s pressed into the army, and I don’t know if he lives or not” and as I saw those little children, three of them, looking as the stillness of death had fallen on their spirits, I turned away, thinking as we walked along, of the many other sorrowful hearts in the land.

While passing themselves off as “good Southern soldiers,” the trio was forced to hide a whole night in a plantation’s cotton pen. About November 18, they fashioned a homemade raft and crossed the Red River into Indian Territory. The men soon came to “rolling open country” and felt safe they were out of the reach of tracking dogs.

About midnight we lay down and were lulled to sleep by the howling of wolves, and our slumbers were neither sound [n]or unbroken. The next forenoon we traveled through a wild but beautiful country, and near ten o’clock came to an Indian village—Choctaw—and by signs made them know we were hungry, when they set out venison, sweet potatoes, curdled milk, and a kind of drink made from roots that had more of the flavor and aroma of Mocha than any imitation of coffee I ever drank. Their houses were substantial one-story hewn log structures, and very comfortable, the inside floored neatly and the air of half civilization was toned down by a cheap print of some missionary that hung on the walls, and a [B]ible in their language lying on a stand. Seeing this, I took from my pocket a small Testament (a gift from my father, and the last relic—other than one picture that I had of home) and by signs made them know it was the same. I fancied the woman’s face wore a kindlier look.

The three now traveled at night, never sure of the loyalties of those they encountered in Indian Territory, since its tribes had men fighting on both sides. After traveling through rolling hills, they emerged to find easier trekking in a valley.

Walking on till eleven o’clock in an easterly direction, we stopped at a small house, from which about half the things had been removed. Taking possession of the premises, we killed a fat pig and rifled a beehive, having for our suppers fried pork and honey. A feather bed that had not been removed, we put down before the fire and laying down upon it, we slept till three o’clock in the morning, when we started on, we passed through a camp of some kind, and soon crossed the Arkansas line. After sunrise as we seemed drawing near to settlements, I wrote a pass (McGregor had pen, ink and paper) and signed Gen. [William] Steel[e]’s name to it, C.S.A., and armed with this we took the State road, traveling rapidly till nine o’clock, when we stopped for breakfast at Judge Nichols, where they told us our cavalry had eaten supper the night before, so we felt near home. While eating in the kitchen, Mrs. Nichols stepped to the front door and said: “Here comes some of your boys now,” I arose, and going to the window, looked out, seeing three soldiers in full Federal uniform which satisfied me of their being our friends; but hardly had I resumed my seat when Mrs. Nichols cried out in alarm that some bushwhackers were coming, and our boys and they would fight there; but from the friendly greeting that passed between them in the road we knew that they were not at enmity. They entered the house, sitting around on chairs, beds and tables promiscuously, with shotguns and squirrel rifles. We could hear their rough talk from the kitchen, and trembled at our probable fate but the crisis had to come, so putting on an unconscious look, we arose from the table and entered the room. To meet the curious gaze of ten or twelve pair of eyes peering from out the hairy faces of roughly dressed men, without flinching or changing color, was the task successfully accomplished. When one at last ventured to ask us who we were, I…answered, we were paroled Federal prisoners sent through to our lines by Gen. Steele, whose army lay in or near that part of the country we had passed over. Then one of them who plainly prided himself on his shrewdness and knowledge of business said, “you’d orter hev a showin or paper”[;] “certainly” said I, drawing forth the pass….He took the slip of paper gingerly betwixt his thumb and fore finger, using it as though momentarily looking for it to evaporate, and turning to a small sharp-eyed red headed man said, “Judge, you’re more on a skollard [sic] than we, read this,” and [the] judge accordingly read it aloud pronouncing it “all squar,” which verdict being echoed by the others a mountain lifted itself from my heart. Not to seem hurried, we sat a half hour promising to “jog along a bit further fore night.”

When Horatio Anderson caught a chill as they proceeded, they stopped at the first house they came upon.

The people received us kindly; we told them who we were, and they got us something to eat; while sitting by the fire talking over the war, the clatter of iron hoofs was heard and in a minute the two doors were opened at once admitting three roughly clad brutal-looking men each with a drawn revolver…[W]e surrendered, and were at once subjected to a searching ordeal of questions to determine if we were all right but with the aid of our forged pass we satisfied all of the party but one, who knew too much, and he had us taken back six miles to a house to find their Captain to see what disposition to make of us. During that midnight tramp, Cook [one of the captors] several times promised us he would see to it that our blood and bones enriched Arkansas soil. Reaching the house, the Captain was not found, so we were allowed the privilege of lying on the floor before the fire, which was a comfort we enjoyed.

After a substantial breakfast…we left, following a devious and untraveled track, round hills and through broken hollows, till at last through the avenue of trees a dim smoke curling upward, marked the camp of the wild men. The throng around the fire opened as we drew near…and stared at us with rude surprise. They never took a Federal prisoner farther than a convenient spot for killing.

In the motley crowd that assailed us with questions, were white-haired old men and smooth-faced ruddy-cheeked boys, half-breed Choctaws, with a wide mouth and little glittering eyes; men clad in beaded buck-skin, butternut homespun, and stolen broadcloth. Lying around were saddles, bridles, guns, sabers, and all the paraphernalia of camp life. Until this time the hope had lingered that I might impose the pass on the guerrilla captain, but seeing him dissipated that hope. His name was J.B. Williamson, a lawyer of some repute in Kentucky, and a man of pleasing appearance and engaging address, so I wisely refrained from the attempt to prevaricate longer. The morning [of] the 23d of November, we were taken into their camp and were with them till Dec. 6th, [and then] sent to Washington, Ark.

One afternoon two more prisoners were brought in—citizens—an old man and his son….It seemed he had been talking plain English to them in response to their queries as to his status on the war, for they were in very ill humor. The fact that he had once for a few years lived in Texas operated strongly against him. The bushwhackers gathered around him with angry faces and bitter words, till having talked and swore their courage up to the sticking point, they led him off into the woods with a rope around his neck and a gun cocked at his breast. He was told if he would not go before his God with a lie in his mouth, to answer their questions truly or renounce his loyalty to a n—- loving Government, but the fear of death was not so strong as the fear of dishonor, and the old man was firm. At length some of them, becoming ashamed of their unmanly work, had him brought back into camp, and when we were sent to Washington, he and his son went along.

The 6th and 7th we had a long and muddy tramp,—seventy miles, and the next day were lodged in the upper story of the county jail, a strong double log building with four windows…having no glass or sash, but heavy iron bars across and up and down, leaving between, spaces about eight inches square…[there were] over sixty men, some having been for months without a change of clothing.

Men were confined there for horse-stealing, mutiny… murder, and every other crime,—Christians, Indians, Half-breeds; men stooped with age, and boys of fourteen, old river gamblers, and now [we] were added…“Yanks” and the gray-haired Still and son, who were worse than Yanks.

To think of escape from this place seemed worse than futile, for not only was the jail in the center of a town of about two thousand inhabitants with soldiers camped around, the windows all strongly barred, and men inside with us who would inform of any attempt of the “Yanks” to get away, and on each side of the building paced a sentinel day and night. Yet escape was talked of, and when our relief stayed up at night that the others might sleep, a large knife made its appearance from the leg of my boot, and worked away very industriously, cutting through a log upon which rested one of the perpendicular bars, and after each night’s work scraping dust and dirt and chips into the opening, covering the whole with ashes.

On Christmas Eve, the three Iowans and William Greer, a local man who had been “laying out,” escaped out the jail window. For a week they avoided Rebel cavalry and guerrillas until “we were overtaken by a snow storm that soon covered the ground three or four inches deep.”

Nine o’clock New Year’s night [1863-64] found us within a few miles of our pickets, and so nearly frozen to death, we stopped at a house careless of the result. Once by a warm fire, irresistible drowsiness overwhelmed us, and we stayed all night. Early the following morning a scout of twenty-two rebels surrounded the house, took us, tied us two and two, and back to Camden [Ark.] we rode through the cold. At Camden [125 miles from Little Rock] we were put to work as scavengers, and I refused to work.

Col. E.E. Portlock Jr., commanding the Post of Camden,…ordered his Post Adjutant to handcuff me, which he did roughly, and passing a rope under the steel band, he swung me up by the wrists clear of the ground, striking me with his cane, and saying: “That’s the way we break our n—–.” Leaving me with the consoling assurance that there I should hang till I worked or died, of which after pondering over about an hour, and getting faint and sick, I chose the work. The remainder of the time we were at Camden, the Federal prisoners were made to husk, shell and sack corn for their army, carry railroad iron for fortifications and much other hard work. The latter part of January, we were taken to Shreveport with several others…

At Shreveport, we were shut up in an old brick wareroom with a brick floor and no windows. Not light enough came through the dusty panes above the door to enable us to wage successful war against “Greybacks.” Here we lay through cold damp days and long sleepless nights, eating the pittance of coarse half-cooked corn cake and beef without salt, until the last of March, when we were taken to the rest of the prisoners, who were on their way to Tyler.

Dungan’s odyssey lasted five months, though he was never more than 220 miles from Camp Ford. Fellow fugitive Horatio Anderson escaped to Shreveport in February, and later that summer all 19th Iowa prisoners were exchanged. On July 24, they rejoined the regiment in federally occupied New Orleans. In the spring of 1865, the 19th took part in fighting around Mobile, Ala., and eventually mustered out in July.

_____

‘Blood marked their tracks’

Ogilvie Donaldson was 25 years old when he mustered in as a corporal in the 19th Iowa Infantry in August 1862. Hard battles and active campaigning would take a toll on him, of course, but his lack of shoes while a prisoner was probably his biggest challenge.

In September 1863, Donaldson was among about 200 men in his regiment captured at Stirling’s Plantation and sent to Camp Ford. News eventually arrived that the regiment and others there were to be exchanged. The men had marched through Shreveport on their way to Tyler, but now for the exchange they were heading back—again by foot. It was a 100-mile trek and few men had shoes or heavy coats as the November cold settled in. “Over the frozen rough road and through ice-bound streams, those barefooted and half-clad five hundred marched, leaving on many a spot of Texan soil drops of blood from bruised and swollen feet,” wrote one 19th Iowa man, adding, “The sun at midday thawing it out only enough to make a cold slush, then toward night freezing again.”

When plans for an exchange at Shreveport fell through, Donaldson and the others had to spend the winter camped a few miles from the city, huddled in improvised huts. In March 1864, they returned to Camp Ford. While there, word came of another exchange. It was July, and instead of frozen ground, unbearable heat beat down on the weakened men as they tramped to Shreveport. “[T]he

hot dust and pebbles blistered our shoeless feet, while hickory leaves bound ’round our head served as hats…”

When they eventually reached New Orleans on July 24, a local paper reported: “[O]ur citizens were astonished by the apparitions of a regiment, the like of which certainly never marched through the streets of any Christian city. Hatless and shoeless, without shirts and even garments that decency forbids us to name….[A]s their bare feet pressed the sharp stones, the blood marked their tracks.”

Donaldson’s medical record read like an encyclopedia of gastrointestinal ailments, including diarrhea, dysentery, and the flux. Home in Iowa, though wracked by the effects of frostbite and scurvy, he returned to his life as a farmer. But his deepest wounds weren’t physical: For years he kept a pair of shoes in every room—a stark reminder that he would never again be without.

Rick Barram, a history teacher from Red Bluff, Calif., is the great-great-grandson of the 19th Iowa’s Ogilvie Donaldson. He has no plans to walk barefoot across Arkansas in solidarity with his Hawkeye ancestor.