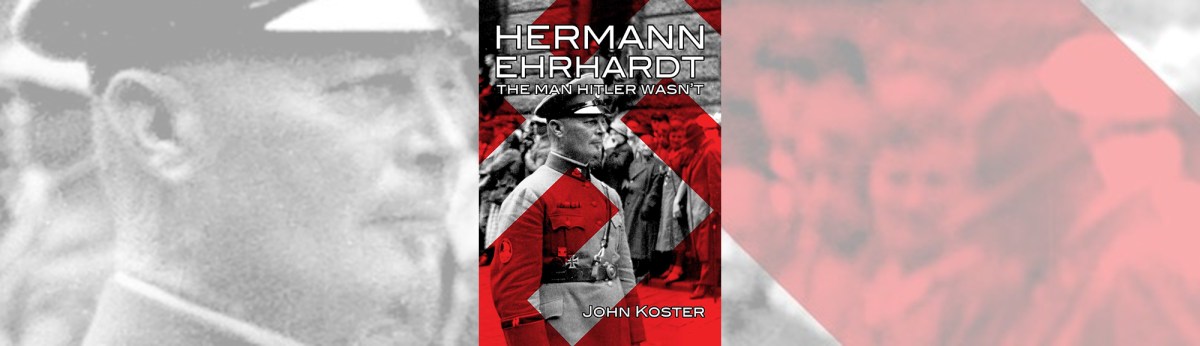

Hermann Ehrhardt: The Man Hitler Wasn’t, by John Koster, Idle Winter Press, Portland, Ore., 2018, $19.99

German history between the world wars is often simplified as a virtual civil war between Bolshevik communists and right-wing Freikorps, while a shaky Weimar Republic helplessly watches its imminent demise. Next thing everyone knows, it’s 1933, and Adolf Hitler and the National Socialists are in power, laying their special plans to make Germany great again.

The truth of what transpired in those 15 years between Armistice and Adolf was far more complicated. The forces involved in Germany’s post–World War I political struggle, left and right, were subdivided into fragments covering a spectrum of philosophies and agendas. Among the more prominent figures in the anti-communist camp, other than Hitler and his growing clique, was a naval hero from the last war, whose record included command of a destroyer flotilla at the 1916 Battle of Jutland. Hermann Ehrhardt’s postwar motives included a desire not only to stop the westward march of Soviet Bolshevism in Europe, but also to revive the monarchy. Although he played a prominent and successful role toward the former goal, fate ultimately drove Germany down another path along which Ehrhardt could not—and had no desire to—march.

Military History contributor John Koster did a level of delving usually reserved for the likes of Hitler to research Hermann Ehrhardt: The Man Hitler Wasn’t. Although the overall violence of the times and Ehrhardt’s own flirtations with ruthlessness prevent this from being a hagiography, the author betrays more than a little sympathy for his subject in the course of refuting many misconceptions and misrepresentations that various political groups, pro and con, have placed on Ehrhardt. What ultimately emerges is a thug caught up in thuggish times who retained enough old values to draw a line that most of his contemporaries saw fit to cross.

Setting him in the context of the era among all with whom he associated, Koster’s book presents a reappraisal in unprecedented detail and nuance of one of those post–World War I imperial German figures who might have steered his country in a somewhat different direction than the one it took—if only a contemporary of his, one Adolf Hitler, had not prevailed. In the course of documenting their differences, the author will undoubtedly leave some readers speculating on what might have been.

—Jon Guttman