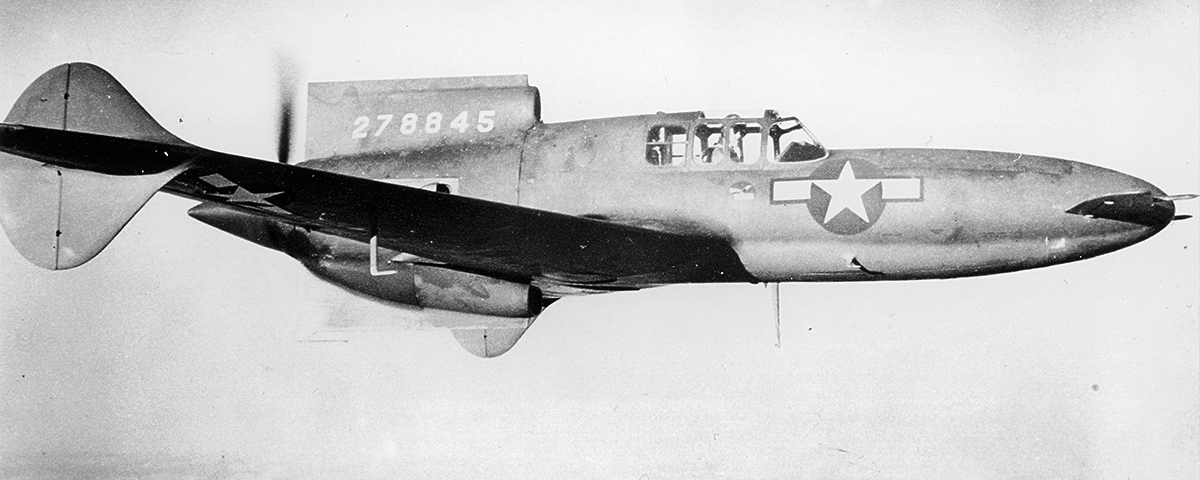

The Curtiss-Wright XP-55 sweptwing pusher was a plane ahead of its time.

“Thinking outside the box” is a catchphrase that is heard perhaps too often today, but in 1939 it had not yet come into wide usage. Nevertheless, the concept did exist—exemplified by U.S. Army Air Corps Major Edward M. Powers’ proposal on November 27, 1939, for an advanced new fighter that would be superior to any existing plane in speed, rate of climb, maneuverability, armament and pilot visibility. The cost was to be low, as was maintenance, and the proposal specifically stated that unconventional designs would be considered.

Curtiss-Wright responded with one of the strangest looking aircraft ever to cross its drawing boards. Under the guidance of the respected designer Donovan Berlin, the company’s engineers designed the CW-24, a sweptwing pusher with its elevator in the nose, and fins and rudders near its wingtips. The plane was also ahead of its day in having tricycle landing gear. Its power plant would be equally radical—the as yet unperfected Pratt & Whitney X-1800. This H-shaped engine, which had 28 cylinders in four rows (2,599 cubic inches of displacement) producing 2,000 hp, was supposed to propel the aircraft at more than 500 mph.

Although Vultee’s XP-54 “Swoose Goose” won the competition, Curtiss-Wright had sufficient confidence in its design to fund building a full-scale flying model of welded steel tubing, wooden wings and fabric covering, powered by a 275-hp Menasco engine. Tested at Muroc Bombing Range (now Edwards Air Force Base) in California, the aircraft performed well, though it only reached a speed of 180 mph because of the engine used. Due to some stability problems, the wingtip fins were subsequently enlarged and moved four feet farther out on the wing, and dorsal and ventral fins were added to the fuselage.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Early Prototypes

A USAAF contract was awarded for the production of three prototypes, with the new plane designated the XP-55 Ascender. Because of development problems with the X-1800 engine, all three Ascenders were fitted with Allison 1710 V-12s, each producing 1,275 hp. The first aircraft (42-78845) made its inaugural flight on July 19, 1943, but was lost on November 15, 1943, during a trial flight with test pilot Harvey Gray at the stick. The V-shaped plane pitched tail over nose and went into an inverted, uncontrolled vertical descent, falling 16,000 feet before the pilot bailed out. The second XP-55 (42-78846) was already nearing completion when that mishap took place, so few modifications could readily be made, but its elevator was enlarged and the tab system modified. Likewise, the balance tabs on the ailerons were changed to spring tabs. That aircraft was flown only under restricted conditions, to avoid the stall zone.

The third prototype (42-78847) had four .50-caliber machine guns installed in the nose. Its wing length was increased, and the elevator limit of travel was also increased to reduce its susceptibility to stalling. This proved to be counterproductive, however, as the travel was so great that the pilot could actually stall the aircraft on takeoff. The elevator was remodified, but the airplane was apparently still susceptible to stalling without warning. A mechanical stall-warning device was added. While 42-78847 survived the testing program, it crashed during an airshow at Wright Field, Ohio, on May 27, 1945, killing the pilot, and also killing the driver and burning four passengers of a car.

The middle prototype (42-78846) eventually had similar modifications made to it as testing continued. But because of the unavailability of the X-1800 engine and continued stability problems, the XP-55 never performed up to anticipated specifications. At the same time, jets were starting to appear, and it seemed likely that they would become the next generation of combat planes. In 1944 the XP-55 project was abandoned. While the name “Ascender” implied the aircraft’s ability to rapidly gain altitude, project engineer E.M. “Bud” Flesh later claimed that he had put one over on the bureaucrats with the name. He pointed out, tongue-in-cheek, that emphasis on the first syllable of the name rather than the middle one would result in a completely different connotation!

Prototype’s Journey

What happened to the second prototype? The last of the Ascenders was flown to Warner Robins Field, Ga., in May 1945. It was subsequently taken to Freeman Field, Ind., to await transfer to the National Air Museum (now the National Air and Space Museum). In July 1946, it went to Park Ridge, Ill., and finally to the Paul Garber Facility at Suitland, Md., where it remained for more than half a century.

In December 2001, it was trucked to the Kalamazoo Aviation History Museum in southwest Michigan. An affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution, the “Air Zoo” already had several historic aircraft. The Smithsonian is very exacting in how restoration should be done on its artifacts, and the Air Zoo restoration crew has tried to follow those rules to the letter in its work on the Ascender.

Needs a Bath

Unlike most aircraft the Air Zoo has restored, the XP-55 arrived “surprisingly intact,” according to project manager Rick Johnson. Considering that the two previous restorations the museum completed were a Waco CG-4A cargo glider that was found rusting in a pine forest in Michigan’s upper peninsula and a Douglas SBD Dauntless that sat on the bottom of Lake Michigan for 50 years, it is understandable that the team was thrilled to be working on an airplane that was substantially “all there.” In fact, when they started removing access panels, the men discovered that the interior components were not corroded by rust. They also discovered penciled engineering lines and markings—even notes left by the technicians to themselves about what they had done to the aircraft.

A good cleaning of some components with an Ivory Soap solution was first on the agenda. Aircraft curator Alan Clark began work on both the dorsal and ventral air-intake/fin assemblies. Made of hand-formed balsa, they had begun to rot. Clark, himself a sculptor, managed to repair the assemblies to such an extent that it would take very close examination to realize they are not 100 percent original. Airframe and power plant mechanic Dave Anderson began the disassembly, cleaning and reassembly of the landing gear. While this was going on, Rick Johnson, Greg Ward and several volunteers began the arduous process of documenting the myriad markings on the wings and fuselage. The entire aircraft was draped in clear vinyl, with the position of each stencil, insignia and logo traced on it—making, in essence, a life-size blueprint of the markings. Digital photos were taken of everything and catalogued, so that when the time came to reapply the markings, they would look like, and be placed in exactly the same positions as, the originals.

The Real Work Begins

Once all of the documentation was complete, the men started removing the original finish by hand, being careful not to damage or degrade the underlying metal. Although it would have been nice—and historically more accurate—to keep the original finish on the aircraft, it just was not possible. Almost 60 years of exposure to the elements had left the finish in less than pristine condition. Moreover, the original skin coat filler had retained moisture and continued the corrosive process that had already begun. A self-etching primer called Vari-Prime was used on the bare skin of the wings, bonding to the metal so that corrosion would stop. A filler that would not retain moisture was then used to smooth out the surfaces and wet-sanded by hand. With several applications of filler followed by sandings, the result was an almost perfectly smooth skin. Then an epoxy primer was applied, followed by sanding, and a finish coat of lusterless acrylic enamel was painted on the wings—olive drab above and light gray below. Then all the markings and stencils were applied. Curtiss employees had evidently not stenciled the aircraft—which was common at that time—but instead used some kind of silk-screen method. A similar process was used to apply the new stencils.

The fuselage metal was deemed in good enough condition to have the epoxy primer directly applied, and at this writing the team is preparing it for the skin-coat filler. Also awaiting attention is the forward canard, which is not a true canard (a small forward wing) but a completely moving elevator. It will be restored in a manner similar to the wings and fuselage.

Originally the museum staff planned to wholly disassemble the XP-55’s Allison engine, but when they took a look at it, they realized they would have to cut several hoses and wires, destroying the integrity of the original installation. Using a borescope, Clark, Anderson and Dick Schaus examined the interior of the engine and determined that little corrosion had occurred. So with the Smithsonian’s blessing, they force-pumped the engine with oil (all moving parts moved freely) and then gave the engine exterior a good cleaning. A soap solution will be used to clean the cockpit interior, and the only attention the canopy needs is some touching up, along with replacements for original Plexiglas windowpanes that had cracked. When assembly is complete—probably within about 18 months—the XP-55 will be placed on exhibit in the Air Zoo’s Education Center. The XP-55 Ascender has to be one of the rarest and most unusual aircraft in existence, and the Kalamazoo Air Zoo staff is proud to be restoring it for posterity. It will join more than 80 other aircraft in the Air Zoo’s exhibition halls, located at 3101 E. Milham Road, Kalamazoo, MI 49002-1700, 269-382-6555. Or visit www.airzoo.org.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2004 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.