Exhausted from weeks of incessant campaigning, Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s 8,000 Army of the Valley veterans hoped that Sunday, July 17, 1864, might afford them an opportunity for some much- needed rest. Some of them had been on the march since late June, when they left the Petersburg lines and headed into the Shenandoah Valley before turning north into Maryland.

After heading south once again and fighting the Battle of Monocacy on July 9 near Frederick, the Confederates had arrived on the outskirts of Washington. Following skirmishes in front of Fort Stevens on July 11, Early realized the capital was too strong to take. Withdrawing on the night of July 12, he headed for White’s Ford, on the Potomac River. “We didn’t take Washington,” Early cracked, “but we scared Abe Lincoln like Hell.”

For the next four days his men marched furiously until they crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains at Snicker’s Gap and reentered the Shenandoah Valley. Early set up his headquarters near Berryville, positioning Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon’s division to guard where Castleman’s Ferry carried Berryville Turnpike traffic across the Shenandoah River. A soldier in Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes’ Division, also nearby, wrote on July 17: “Crossed the Shenandoah…and went into camp…near Castleman’s Ferry…a pleasant bivouac. It was in the midst of a delightful country.” Most of Early’s troops took the opportunity to rest, while some used the day for religious reflection. Some Confederates, including General John C. Breckinridge, attended services at Berryville’s Grace Episcopal Church.

But while the Rebels rested and prayed, the Union pursuers who had dogged Early since he left Washington were still on his trail. Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright of the VI Corps commanded that effort, along with troops of the XIX Corps and men from the VIII Corps led by Brig. Gen. George Crook—about 10,500 men overall.

Breckinridge’s Sabbath observances were interrupted when a Confederate courier entered the church and informed the general that a contingent of Federal troops, Colonel James Mulligan’s infantry brigade and troopers from Brig. Gen. Alfred Duffie’s cavalry division, had crossed Snicker’s Gap and engaged Confederate pickets near Castleman’s Ferry. Duffie’s cavalry had reached Snicker’s Gap, at the summit of the Blue Ridge, around noon on the 17th, and although Duffie initially reported “meeting with no opposition from the enemy,” that situation would change as his troopers descended the mountains’ sparsely forested western face and came within range of Gordon’s Division on the river’s western bank. A veteran of the 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry noted that the “thinly wooded” slope “gave the enemy on the opposite side of the river a fine view of our movements, and they soon opened on us a fierce artillery and musketry fire.” Early’s defenders compelled Duffie to withdraw the bulk of his command to Snicker’s Gap at nightfall.

That afternoon’s melee prompted Early to take necessary precautions to defend the crossing. Around 10 p.m. he directed Breckinridge to have his “troops…under arms at daylight…and if any attempt at a crossing is made, he wishes the most determined resistance made to it.”

Meanwhile eight miles to the east in Purcellville, General Wright gave final instructions to Brig. Gen. George Crook to march west on the morning of the 18th and “develop the enemy” along the Shenandoah’s banks. Wright, unaware of the difficulties confronted by Duffie’s command on the 17th, believed that Crook’s task would be easy, and sent a message to Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck in Washington that evening: “I have no doubt that the enemy is in full retreat for Richmond.”

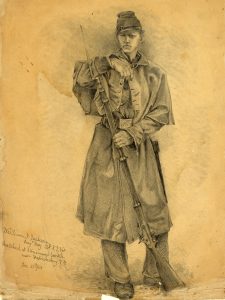

Around 4 a.m. on July 18, Crook put his command of approximately 4,000 men in motion. As his weary regiments marched west toward Snicker’s Gap, his men pondered what the day would bring. Corporal Charles J. Lynch of the 18th Connecticut wrote in his diary: “Up… early…this fine morning…we cannot tell what an hour may bring.”

Approximately five hours after Crook’s troops left Purcellville, his regiments reached Snicker’s Gap. The chaplain of the 18th Connecticut recalled that the “scene was both inspiring and exciting. From that point could be seen the beautiful valleys of Loudoun on the one hand, and the Shenandoah on the other.” But the presence of Confederates across the river’s opposite side sobered the Federals.

As Crook’s troops filed into Snicker’s Gap, a contingent of 75 troopers under Major George T. Work were preparing for another attempt at crossing the river. When the Pennsylvanians splashed into the river, salvos from Major William McLaughlin’s artillery battalion forced the troopers back. A frustrated Crook, who had been observing them, said he believed the Pennsylvanians “had done all that men could have done under the circumstances.” He decided to send Duffie’s cavalry nine miles south to Ashby’s Gap, in an effort to attack Early’s wagon trains and seal off any potential Confederate retreat—depriving the Federals of horsemen who might have proved useful later that day in gathering information about the true strength of Early’s army.

As Duffie’s horsemen trotted off to Ashby’s Gap, Wright and Crook conferred. The generals had no idea of the total strength of Early’s command and agreed to flank the Confederate position by crossing approximately two miles upstream.

Around 2 p.m. Crook ordered Colonel Joseph Thoburn to take his small division and Colonel Daniel Frost’s brigade, approximately 5,000 men, to cross the Shenandoah at Island Ford, north of the Confederate position, then turn south and “dislodge…the enemy.” Thoburn had difficulty navigating the narrow paths to cross at Island Ford. With the aid of a local guide, John Carrigan, a musician who had deserted from the 2nd Virginia Infantry, Thoburn’s command traversed mountain paths down the slopes of the Blue Ridge and tramped across the Retreat, a farm owned by Judge Richard Parke. Shortly after 3 p.m. Thoburn’s van under Colonel George D. Wells crossed the river at Island Ford.

As Wells’ troops plunged into the Shenandoah, a small contingent of Confederate pickets from the 42nd Virginia Infantry opened fire. A veteran from Colonel William Ely’s brigade observed the crossing and watched the Union infantry as they “pushed across and captured the Rebel picket of 15 men, and the captain commanding them.”

The remainder of Thoburn’s force crossed uncontested, though a veteran of Wells’ command recalled that some men struggled with the “very slippery” river bottom. Thoburn’s infantry took position on the Shenandoah’s west bank, and skirmishers advanced across the Westwood Farm along the river’s western shore, proceeding to a ridge at Cool Spring Farm. Thoburn meanwhile questioned the Confederate prisoners and learned that “the divisions of the rebel Generals Gordon and Rodes were within a mile or two of the ford, and that General Early was present.”

Unnerved that his small command had become separated from the remainder of the army, Thoburn immediately sent a courier to Crook “for further instructions.” Crook told Thoburn not to turn south, as previously ordered, but instead “to take as strong a position as possible near the ford and await the arrival of a division of the Sixth Corps.”

Once Thoburn’s entire command was across the river—approximately 4 p.m.—he deployed skirmishers on an upland ridge just east of the Cool Spring mansion and established his first line about 75 yards from the river’s western bank. Thoburn then posted a second line in reserve on “an old road on the riverbanks and behind a low stone fence,” a position which Thoburn wrote after the battle “afforded excellent protection for the men.” The line, which due to the terrain’s contours looked more like an arc rather than a straight line, was anchored in the center by Colonel Daniel Frost’s brigade. Colonel Wells’ command guarded the left, while Thoburn took charge of the brigade on Frost’s right flank. A provisional brigade commanded by Colonel Samuel Young—approximately 1,000 men from 27 different cavalry units fighting as infantry—protected the Union line’s extreme right flank.

With battle now imminent, many of Thoburn’s waterlogged veterans were thinking of loved ones at home. When Colonel Frost visited friends in Wells’ brigade, he proudly showed off “some new photographs of his family that he just received,” as brigade member B.J. Bogardus recalled. Bogardus also noted that Frost, who seemed tired of war, had stated that “he would give his interest in the Government” to see his family again.

A soldier of the 4th West Virginia noted that they remained in “position…for nearly an hour without…scarcely any indication of the enemy.” But meanwhile Confederates from Gordon’s, Wharton’s and Rodes’ divisions had been en route to Cool Spring Farm since the first eruption of small arms and artillery fire, signaling Thoburn’s crossing at Island Ford.

By 5 p.m., from their perch atop the Blue Ridge, Wright and Crook spotted the approaching Confederate divisions. Unnerved, Crook informed Wright that he wanted to immediately “withdraw my troops to our side of the river.” But Wright demurred, informing Crook that he “would order Gen. [James] Ricketts to cross the river and support…with his division.”

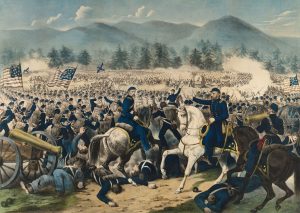

From the river’s east side, Lieutenant Jacob H. Lamb’s Battery C, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, tried to stymie the Confederate advance. Lamb reported firing 90 rounds, though it did little to slow the Confederate divisions. Soon sharpshooters from Gordon’s and Wharton’s commands appeared in front of Thoburn’s skirmishers and forced them back toward the main Union line. While Wharton and Gordon occupied Thoburn’s skirmishers on the upland ridge, Rodes used the topography to conceal his command and get into position to assault the Federal right.

When Rodes’ infantry burst through a grove of oaks into a clearing on Thoburn’s right, Colonel Samuel Young’s hodge-podge of dismounted cavalrymen at first could not believe their eyes. C.E. McKoy of the 1st Maine Cavalry noted that Rodes’ Division “advanced from out the woods in our front.” Young’s men realized that in order to maintain a successful defense, they had to seize a stone wall that traversed the uneven terrain perpendicular to Thoburn’s main line. Troops from Rodes’ Division and Young’s dismounted troopers soon both dashed for the wall. Rodes’ infantry secured it first, sending Young’s command into a panic and compelling many to retreat across the river. Young, who is remembered “as brave a man as ever straddled a horse,” tried desperately to rally his command, but could not do so. During their retreat, some of his soldiers drowned in “Parker’s Hole”—a deep abyss in the riverbed.

With Young’s command in disarray, the task of holding the right flank fell upon Colonel John L. Vance’s 4th West Virginia. Some men in Vance’s regiment carried discharge papers in their pockets, but one West Virginian noted, “the Fourth boys being plucky fellows generally, these discharged men said that they would not stand back while their comrades were going into a fight.” Vance’s troops, however, were left “wholly exposed,” as one veteran recalled, “to a galling fire” from Rodes’ infantry, and Vance ordered the entire regiment to pull back to the cover of the stone wall along the river’s western shore.

As the situation worsened, Thoburn ordered Colonel James Washburn’s 116th Ohio from the southern end of the line to bolster the right flank. One Buckeye recalled that as they arrived they saw “a large body of rebels…bearing down heavily on the right…and the gallant 4th West Virginia fighting to maintain its position against desperate odds.” Just as Washburn arrived on the right flank, a Confederate bullet pierced his left eye, exiting his head below the right ear. Although Washburn and his men believed the wound must be fatal, the colonel would survive.

Now under the command of Lt. Col. Thomas Wildes, the 116th Ohio prepared to block Rodes’ assault. Wildes believed the most vulnerable part of the right flank was the area between the stone wall that ran parallel with the Shenandoah and the river’s western bank, and he ordered Captain Thornton Mallory to take two companies to throw “up a breastwork of stones and logs across this space.”

As Thoburn shifted troops to meet Rodes’ assault, Crook accompanied General Ricketts to the river to see where Ricketts’ division could cross and support Thoburn’s beleaguered brigades. But Ricketts, as Crook later remembered, “refused to go to their support” after seeing the great strength of the Confederate assault. Crook sought Wright’s intercession in the matter, but he agreed with Ricketts.

While Crook argued with Ricketts, the beleaguered Thoburn continued to shuffle regiments to meet Rodes’ assaults and ordered Colonel Daniel Frost to shift his brigade so that it faced to the north and presented “a front to the advancing foe.” While moving his brigade Frost fell mortally wounded. That loss, coupled with the heavy fire that Wharton’s Division poured into the left flank of Frost’s regiments, soon had the Union troops in a confused frenzy, and the panic spread into one of the units in Wells’ brigade, the 5th New York Heavy Artillery.

As Frost’s Pennsylvanians and West Virginians and the 5th New York broke, they struggled to cross the Shenandoah as quickly as possible. Some drowned in Parker’s Hole or fell victim to Confederate sharpshooters. Although large numbers of Thoburn’s command fled from the field by about 6 p.m., others believed their bet option was to stay and fight. “The river at our back was too deep to more than walk slowly through,” noted a 116th Buckeye, “and so escape…was out of the question….Nothing was left to do but fight.”

The troops who stood on Thoburn’s northern flank that evening—the 116th Ohio, 4th West Virginia, 12th West Virginia, and remnants of the 1st West Virginia, Second Maryland Eastern Shore, 18th Connecticut and Young’s dismounted cavalry who did not retreat—fought with unparalleled tenacity, fending off three assaults by Rodes’ Division. “I do not remember to have been engaged in a more sharp and obstinate affair….Like hailstones flew furiously the missiles of death,” recalled one of Rodes’ soldiers.

As Thoburn’s remaining stalwarts thwarted everything Rodes could throw at them, Colonel Charles H. Tompkins, Wright’s artillery chief, deployed 20 cannons—Batteries C and G of the 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery and Battery E, 1st West Virginia Artillery—to allow Thoburn’s remaining infantry to withdraw safely across the river. A correspondent for the New York Herald attached to Wright’s command noted that Tompkins’ gunners executed “some of the best shooting ever seen in modern warfare.” While Tompkins’ 20 guns indeed helped stop the Confederate offensive, some Union shells—due to the closeness of Union and Confederate battle lines—occasionally landed among Thoburn’s command.

Once darkness fell, Thoburn’s remaining infantry withdrew to the east side of the river and tried to make sense of what had happened—why had 65 of their brethren been killed, with another 301 wounded. Could the sacrifice have been avoided? An officer in the 34th Massachusetts, part of Colonel Wells’ brigade, wrote that his comrades felt “soured and chagrined” as they speculated on who was responsible for “the blunder.”

Meanwhile, the troops in Gordon’s, Wharton’s and Rodes’ Divisions—despite the loss of approximately 400 men—reveled that they “drove” Thoburn’s troops “across the river, with heavy loss and in much confusion.” An Alabamian who participated in the battle wrote with pride in his diary that “It was quite a fierce little contest….We made the Yankees take water and get back on the side of the river from whence they came.”

Throughout the day on the 18th, pickets exchanged fire and occasionally lobbed artillery shells at each other. On the 19th Early received the startling news at his Berryville headquarters that a Union force under Brig. Gen. William Averell “was moving from Martinsburg to Winchester.” Fearful that Averell might strike his rear, Early ordered his command to march west toward Winchester and then south to Strasburg on the night of the 19th.

On the morning of the 20th, Federals crossed the Shenandoah and walked across the battlefield. Surgeon Alexander Neil of the 12th West Virginia remembered seeing Union dead “left naked on the field, every stitch of clothing having been taken.” Outraged at this “painful, sickening sight,” the 18th Connecticut’s chaplain wrote that he believed “Everlasting infamy will be attached to the memory of the rebel leaders who allowed the soldiery to treat them with so much neglect and cruelty.”

While certainly not comparable to the many of the war’s key engagements, Cool Spring left an indelible impression upon the troops, particularly Thoburn’s veterans, who fought in the largest and bloodiest engagement in Clarke County, Va. Some veterans in Thoburn’s command seethed with anger about what happened to them for decades, refighting the battle in The National Tribune. Others, such as Colonel Washburn, were scarred for life by the fight—in Washburn’s case, including “partial paralysis of one side of his face,” loss of speech and “partial loss of speech.”

Perhaps Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana best summed up the battle’s futility—and the futility of the war as a whole. He wrote that what happened on the banks of the Shenandoah River “proved…an egregious blunder” and “accomplished nothing.”

Jonathan A. Noyalas is assistant professor of history and director of the Center for Civil War History at Lord Fairfax Community College in Middletown, Va.