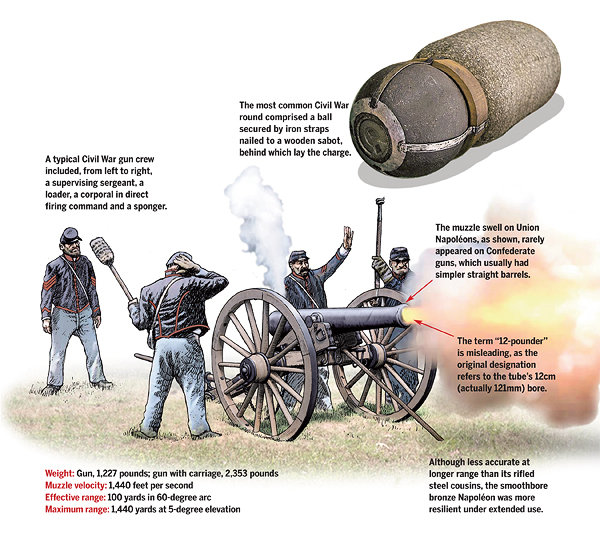

In 1853 France, for neither the first nor last time, revolutionized artillery with the introduction of the Canon obusier de 12cm, modèle 1853—a cast-bronze smoothbore cannon capable of doubling as a howitzer, light enough to be pulled swiftly by a team of horses but heavy enough to destroy fortifications a half-mile away. Safe, reliable and accurate, it was also quite versatile, firing ball, shell, canister and grapeshot, the latter of which devastated infantry at close range. Entering service under Emperor Napoléon III (nephew of that Napoléon), it came to be popularly named after him.

In 1857 the U.S. Army adapted the cannon as the light 12-pounder M1857. When the Civil War broke out, the gun’s simplicity enabled the Confederates to replicate it, making the Napoléon virtually a universal artillery piece, with captured cannon easily pressed into service by either side. Wartime foundries produced some 1,100 Napoléons in the North and 600 in the South. Such was the gun’s effectiveness that in 1863 General Robert E. Lee had all six-pounders in the Army of Northern Virginia sent to the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Va., to be melted down and recast as 12-pounders. The November 1863 Union seizure of the Ducktown copper mines near Chattanooga, Tenn., cut Confederate production of bronze, so Tredegar cast later models of the Napoléon in iron.