Facts, information and articles about Woodrow Wilson, the 28th U.S. President

Woodrow Wilson Facts

Born

12/28/1856

Died

2/3/1924

Spouse

Ellen Axson

Edith Bolling

Accomplishments

28th president of the United States

Woodrow Wilson Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about Woodrow Wilson

» See all Woodrow Wilson Articles

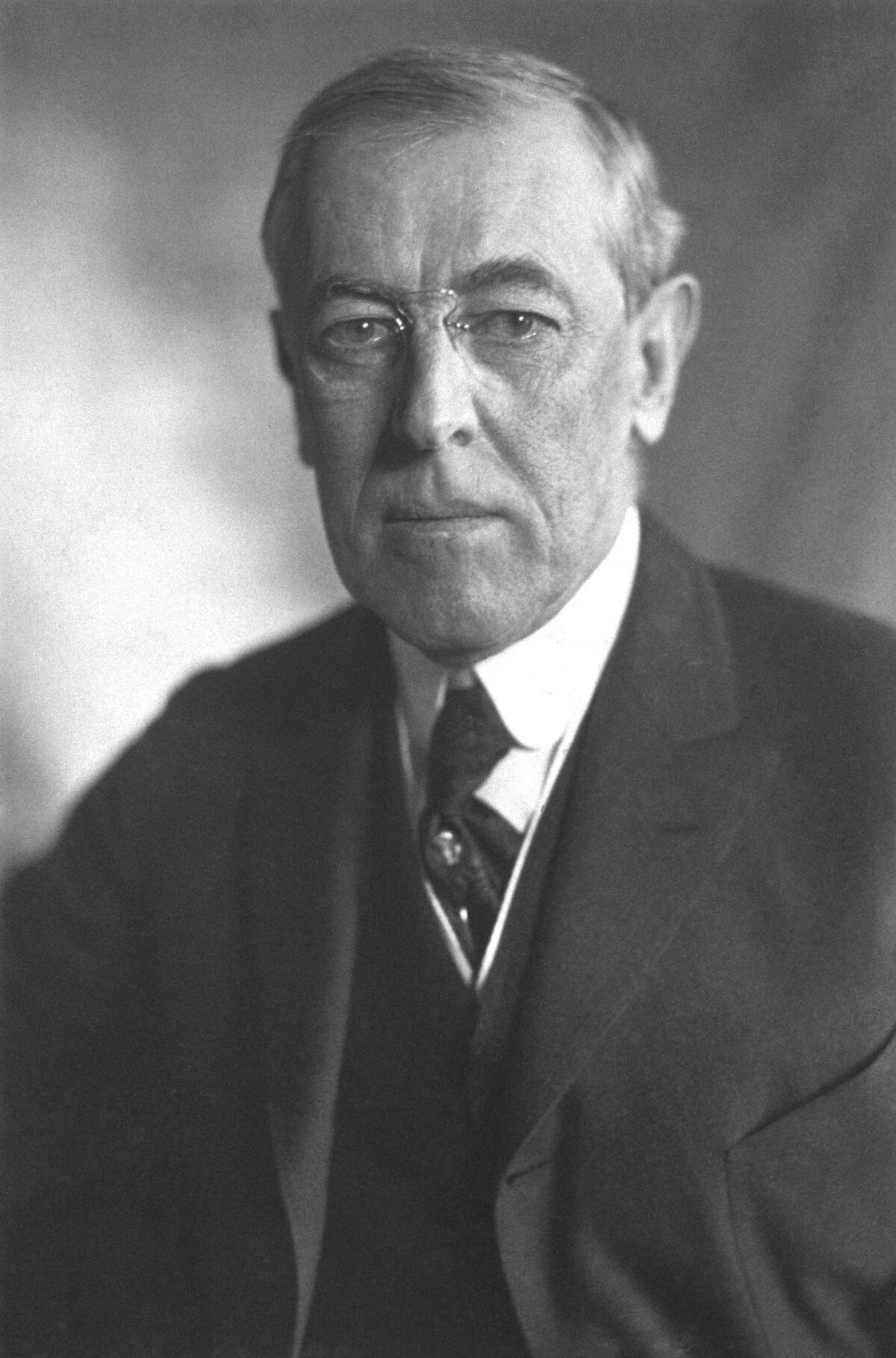

![By Pach Brothers, New York [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons President Woodrow Wilson portrait December 2 1912](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2d/President_Woodrow_Wilson_portrait_December_2_1912.jpg/256px-President_Woodrow_Wilson_portrait_December_2_1912.jpg) Woodrow Wilson summary: Woodrow Wilson was the 28th president of the United States of America. He was born in Staunton,Virginia on December 28, 1856. He was the son of a reverend and traveled quite a bit as a child with his family. He attended college at what is now Princeton University, studied law at the University of Virginia, and earned a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University. He later taught at Princeton, and became president of the university in 1902. He became governor of New Jersey in 1910. He ran for president in 1912 and won, making Wilson the 28th U.S. president. A few items he worked on were the Federal Reserve Act, The Clayton Antitrust Act, The Federal Farm Loan Act, Federal Trade Commission Act and income tax. He was responsible for an agenda that was large and unmatched until the New Deal.

Woodrow Wilson summary: Woodrow Wilson was the 28th president of the United States of America. He was born in Staunton,Virginia on December 28, 1856. He was the son of a reverend and traveled quite a bit as a child with his family. He attended college at what is now Princeton University, studied law at the University of Virginia, and earned a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University. He later taught at Princeton, and became president of the university in 1902. He became governor of New Jersey in 1910. He ran for president in 1912 and won, making Wilson the 28th U.S. president. A few items he worked on were the Federal Reserve Act, The Clayton Antitrust Act, The Federal Farm Loan Act, Federal Trade Commission Act and income tax. He was responsible for an agenda that was large and unmatched until the New Deal.

During his presidency, Wilson was an advocate for farmers and small businesses. He tried to remain neutral when World War I began in Europe in 1914, but finally had Congress make a declaration of war in 1917. Wilson proposed his famous 14 points as part of the Treaty of Versailles; his final point was the creation of the League of Nations. Wilson was awarded a Noble Peace Prize for his attempts at solidifying world peace. After a series of debilitating strokes, his wife, Edith, was believed to have made many important decisions for Wilson while he convalesced; he never permanently recovered. Woodrow Wilson died in 1924, just three years after leaving office.

Articles Featuring Woodrow Wilson From HistoryNet Magazines

Featured Article

How did Woodrow Wilson become America’s most hated President?

A chorus of conservative pundits portray Wilson as the man at the helm when everything began to go wrong for America

The Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist George Will made a startling assertion when he took the podium last year at a banquet sponsored by the Cato Institute, the libertarian think tank in Washington, D.C. “I firmly believe that the most important decision taken anywhere in the 20th century was where to locate the Princeton graduate college,” Will declared.

The university’s president, Woodrow Wilson, then a high-minded political scientist who had yet to run for public office, insisted that the new residential college be integrated into the main campus. But after a lengthy and bitter academic feud, in 1910 the university’s trustees and donors sided with the graduate school dean, who chose a more secluded location adjoining a golf course.

“When Wilson lost,” Will told the black-tie crowd, “he had one of his characteristic tantrums, went into politics and ruined the 20th century.”

The audience chortled and applauded, but Will was only half-joking. Wilson left Princeton for a new career as a crusading politician, and after soaring to national prominence during a short stint as Democratic governor of New Jersey, in 1912 he became the only scholar with a Ph.D. ever elected president of the United States. In his first term, he pushed through a flurry of Progressive-era economic and regulatory reforms, and during the second he was hailed abroad as “the savior of humanity” after America and its allies had won World War I. Wilson remains a top 10 perennial on historians’ lists of outstanding presidents. But as the centennial of his ascension to the White House nears, he has also become a target for an increasingly raucous chorus of conservative pundits who portray him as the man at the helm when everything began to go wrong in America.

Will whimsically refers to Wilson as “The Root Of Much Mischief.” Others are less subtle or circumspect. They blame Wilson for things he did, like creating the Federal Reserve System and implementing a progressive income tax, and for things he didn’t do, like supporting eugenics or causing World War II. “The 20th Century’s first fascist dictator,” National Review columnist and Fox News contributor Jonah Goldberg called Wilson in his book 2008 Liberal Fascism. To tearily dramatic radio talk show host Glenn Beck, Wilson has become nothing less than the source of all political evil. “This is the architect that destroyed our faith, he destroyed our Constitution and he destroyed our founders, OK?” Beck ranted on the air. “He started it!”

Nor is Wilson generating much praise from liberals who might be expected to defend him. Wilson was a bigot who sanctioned official segregation in Washington, D.C., say critics on the left. He used America’s entry into World War I as a rationale for crushing civil liberties. He was autocratic.

Such assaults on an intensely cerebral president, to whom many contemporary Americans have given scant thought since memorizing “League of Nations” for their history SATs, may reflect our ongoing jousting about the proper role of government—a question that intrigued Wilson himself since his graduate school days. They also reflect the fact that another Democrat with an ambitious first-term agenda—Barack Obama—now occupies the White House. If culture wars can rage over museum exhibits, Christmas and nutritional advice, why not over the 28th president of the United States?

“He was what we’d call today a polarizing figure,” says Barksdale Maynard, a Wilson biographer prone to scholarly understatement.

From the bay window of the Princeton president’s office in 1879 Hall, Maynard points out during a walking tour of the university’s spired campus, Wilson could gaze directly down Prospect Avenue at the row of eating clubs he despised and tried in vain to vanquish. It must have been a galling view. Alumni had built these sprawling brick and stone mansions, and the groups had grown so socially important by the turn of the 20th century that hopeful preppies sometimes focused their campus visits on Tiger Inn or the Ivy Club, ignoring the adjacent university where they were supposed to be educated. “Wilson regarded these clubs as antithetical to what he was trying to build at Princeton,” says Maynard. “It was the son of a Presbyterian minister from the South confronting the New York aristocrats.”

So why wouldn’t today’s conservative populists, Tea Party supporters for instance, like Thomas Woodrow Wilson? A God-fearing lifelong churchgoer, he was the son, grandson and nephew of Presbyterian clergy. Never wealthy, he only rented the unpretentious Tudor house, a short walk from the campus, where he lived as governor of New Jersey and where he received the telegram announcing he had won the presidency. “It’s not Mount Vernon,” Maynard notes dryly.

But that hardly seems to matter.

The Wilson-bashing has been stoked in part by conservative academics who have trolled through his papers, copies of which occupy hundreds of acid-free boxes in the rare manuscript library nearby. Scholars and graduate students labored over this enormous project for decades (they had to decipher the old-fashioned shorthand Wilson once favored); the 69th and final volume of papers came off the press in 1994.

Political scientist Ronald Pestritto, whose 2005 book Woodrow Wilson and the Roots of Modern Liberalism drew on that material, used scholarly language but lobbed serious accusations, charging, for instance, that Wilson’s leadership “is not as democratic as it seems, but instead amounts to elite governance under a veneer of democratic rhetoric.” Such ideas soon began cropping up in more popular writing, like Jonah Goldberg’s 2007 book, which describes Wilson as an imperialist, totalitarian warmonger who, from his youth, was “infatuated with political power” and then corrupted by it.

Glenn Beck read Pestritto’s book at the recommendation of political philosopher Robert George, who now holds the chair created for Wilson at Princeton and is among his gentler conservative critics. But there’s nothing gentle about the way Beck has vilified Wilson in his best-selling books, on a syndicated radio broadcast that reaches an estimated 10 million listeners a week, and on a daily Fox News television show that the network pulled the plug on in June 2011. He blasts Wilson as an “S.O.B.,” charges that he “perverted Christianity” and ranks him No. 1 on his “Top Ten Bastards of All Time” lists—ahead of not only both Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, but also Pontius Pilate, Hitler and Pol Pot.

Even the conservative Weekly Standard scolded Beck, declaring, “This is nonsense. Whatever you think of Theodore Roosevelt, he was not Lenin. Woodrow Wilson was not Stalin.” That hasn’t slowed Beck’s assault. He consoles himself, he has said, by looking up from his desk at a treasured gift: a framed front page of a 1924 newspaper headlined, “Woodrow Wilson Is Dead.”

Many presidents’ standings wax and wane over the decades, of course. “I don’t think any statesman can sleep soundly in his grave,” says Robert George. But rarely has a debate about a historic figure’s accomplishments and shortcomings turned so vitriolic. So whence this wave of animosity? It starts with the progressive movement that helped elect Wilson and that also can claim Theodore Roosevelt. “In a nutshell, the argument is that this marked the first era in American history where prominent national leaders were openly critical of the Constitution,” Pestritto explains.

The criticism can sound fairly innocuous: Reformers like Wilson contended that a system of government established in the late 1700s for a smaller, sparsely populated country had become inadequate in a world of industrialization, immigration, international tensions and other developments the founders couldn’t have foreseen. Government therefore had to adapt.

“The Constitution was not meant to hold the government back to the time of horses and wagons,” Wilson wrote in his scholarly tome Constitutional Government in the United States (1908). He deplored the way the branches of government checkmated each other to stall progress—or what he saw as progress—and admired the British parliamentary system as more efficient.

The problem, in the conservative critique, is what results. In George Will’s words: “Concentrate as much power as possible in Washington, concentrate as much Washington power as possible in the executive branch and concentrate enough experts in the executive branch” to administer a much larger government. And it was Wilson, adds Robert George, who made progressivism “a doctrine, not just a sensibility. He’s the guy who laid out the justifications and ideas.”

Perhaps, though, it’s less Wilson’s ideas that trouble his critics than what he managed to do with them, especially in his first term as president. “His greatest domestic achievement was the creation of the Federal Reserve System, and that’s probably enough for Glenn Beck in itself,” says Thomas J. Knock, a historian at Southern Methodist University and another Wilson biographer. But the list goes on: The Federal Trade Commission. The Clayton Antitrust Act. The first downward revision of the tariff and the implementation of the progressive income tax (though the 16th Amendment was actually passed and ratified just before Wilson took office). The first federal law establishing an eight-hour day (for railroad workers). The first federal law restricting child labor (later struck down by the Supreme Court). The appointment of Justice Louis Brandeis, the first Jew to serve on the Supreme Court.

Wilson’s second term was another matter. He couldn’t live up to the campaign slogan “He Kept Us Out Of War,” of course, and some supporters never forgave him for America’s immersion in the mechanized horrors of World War I. Nor did he succeed in engineering American participation in his cherished League of Nations, though he—literally—nearly died from the physical stress he experienced trying. But his blazing domestic record includes actions some conservatives condemn to this day.

“If those on the right want to blame him, put him in the pantheon, the Hall of Shame for people who expanded the state and made it more interventionist, especially in the economy, fair enough,” says University of Wisconsin historian John Milton Cooper, author of several Wilson biographies. “He belongs there.”

The thing is, he’s got plenty of company.

Why not turn, for a presidential piñata, to Theodore Roosevelt, who was ramming through progressive legislation before Wilson ever entered politics? In the 1912 election, each vied to portray himself as the greater advocate of strong government. Why not lambaste Franklin Roosevelt, whom Wilson appointed to his first national post, assistant secretary of the navy? Surely FDR’s New Deal proved at least as threatening, to those with a taste for limited government, as Wilson’s New Freedom agenda.

One could argue that talk radio hosts have a penchant for discovering and trumpeting supposed hidden truths, revealing to their listeners what high school textbooks, college curricula and the media (all, in this scenario, controlled by conniving liberals) have concealed. Attacking FDR is way too obvious; everyone knows he steered the nation leftwards. Wilson’s role as the alleged destroyer of the Constitution makes for more piquant programming. Or perhaps Wilson’s academic background, seen as an asset at the time, brands him a member of the Eastern elite, despite his middle-class Southern upbringing. He was the ultimate pointy-headed intellectual; editorial cartoonists delighted in portraying him in a cap and gown.

Or one could theorize, as John Milton Cooper does, that there’s a simpler explanation: Americans just don’t cotton to Woodrow Wilson. That it’s unpatriotic or dangerous to criticize the Constitution strikes Cooper as a nonsensical argument—what are all those amendments for if the founders were so unerring? But he has noticed that among the presidents who top historians’ lists, “sooner or later you get the glow of universal acceptance and acclaim.” To his sorrow, “that has never happened to Wilson.”

Case in point: Theodore Roosevelt. Given the passage of a full century, plus a little selective memory, liberals can applaud the progressive trustbuster and conservatives the rugged Rough Rider. “TR tends to enjoy a certain above-the-battle reputation,” Cooper says. “People just don’t want to go after him.”

Even FDR, hardly beloved by conservatives, got plenty of laudatory press during the 1982 centennial of his birth, Cooper points out. Roosevelt fought the unambiguous Good War, after all, and saw the nation through the Depression; meanwhile, millions of Americans continue to rely on the social safety net he constructed.

But Wilson seems fair game. “He rubs people the wrong way, for some reason,” Thomas Knock concurs. In historic reputations, as in contemporary political polls, personalities matter. Theodore Roosevelt so often looks, in his grinning photographs, like he’s having a ripping good time. Wilson, with his long face and severe pince-nez glasses, looks like he’s headed for a dental appointment. Roosevelt once referred to him, in fact, as resembling “the apothecary’s clerk.”

The distaste extends to those on the left who would normally be Wilson’s allies and defenders—this was a man once endorsed by legendary labor organizer Mother Jones and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois, no less—primarily for two reasons. First, he held typically unenlightened views on race. Born in Virginia and raised in Georgia, he paid little attention to blacks’ legal or economic plight. As Princeton’s president, he refused to consider admitting black students at a time when Ivy League rivals Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania had begun to accept them.

Later, as a president who gave considerable autonomy to his Cabinet members, many of them fellow Southerners, he acquiesced as they set about segregating the Postal Service, the Treasury Department and the Bureau of Printing and Engraving; during Wilson’s administration the number of black government employees actually declined. He also permitted a gala White House screening of D.W. Griffith’s hateful epic The Birth of a Nation, apparently as a favor to someone he had briefly attended school with; though he later tried to disassociate himself, the incident outraged the protesting NAACP.

Black leaders subsequently declined to support his reelection. “We need scarcely to say that you have grievously disappointed us,” Du Bois wrote.

“By any reasonable standards anyone would apply today, I think it’s fair to say Woodrow Wilson was a racist,” historian John Milton Cooper acknowledges, regretfully.

That other presidents also qualify doesn’t shield Wilson from contemporary scorn. Middletown, Connecticut—where Wilson once taught at Wesleyan University—named a public school in his honor in 1931, but in 2004, two high school seniors argued (ultimately unsuccessfully) that the town shouldn’t honor a bigot. “The question I’m asked the most when I talk about Wilson, almost always by some young person in the audience, is ‘What about his racism?’ ” says Barksdale Maynard. “It’s poisoning his reputation.”

Wilson’s reputation also suffers from the Sedition Act and the Espionage Act, laws he supported and signed in his second term, convinced that winning World War I required a crackdown on homefront dissent. Overriding the pleas of onetime supporters, he permitted a variety of transgressions against civil liberties, leading to about 2,000 wartime prosecutions. His postmaster general banned the mailing of a variety of liberal, socialist and radical publications. His Justice Department rounded up and arrested labor organizers. Vigilantes attacked innocent people for the crime of being German American. The socialist leader Eugene Debs, who had run against him in the four-way election of 1912, was tried and sentenced to 10 years for making antiwar speeches.

Wilson remained publicly silent about all of it and refused to pardon the aging, ailing Debs, even after the armistice. “Wilson was a typical Puritan,” H.L. Mencken wrote in 1921. “Magnanimity was simply beyond him.”

In a heated 2008 essay that branded Wilson “an intolerant demagogue,” Harper’s publisher John R. McArthur concluded, “The great proponent of democracy engaged in the most anti-democratic domestic crusade in American history.” A century earlier, Harper’s Weekly had helped propel Wilson into politics; now, disdain for Wilson may be the sole issue on which its publisher agrees with Glenn Beck.

In a way, this ongoing tussle over history’s verdict is old news for Wilson. Historians still credit him with presiding over America’s entrance onto the international stage, and his stock was high when the Allies won the war. But the peace talks in Paris in 1919 turned fractious and punitive, and afterwards Wilson was unable to coax or pummel a Republican-controlled Senate into approving the Treaty of Versailles and, with it, American membership in the League of Nations. A barnstorming cross-country speaking tour, an attempt to sell the Senate on the treaty by selling the public, possibly brought on the stroke that crippled and eventually killed him, and left the country rudderless for the crucial 15 months remaining in his term. Wilson departed the White House a diminished and discredited leader.

Yet his star rose again during World War II, by which time an international organization that could have defused conflicts didn’t sound like such a terrible idea. Journalists and biographers took renewed interest, and Hollywood producer Darryl F. Zanuck spent a then unprecedented $5 million to film a Technicolor extravaganza simply titled Wilson, portraying him as a man ahead of his time. Released in 1944, it was nominated for 10 Academy Awards.

In another 20 years, therefore, bloggers and editorialists may be quoting admiringly from Wilson’s weighty Constitutional Government in American Politics and rattling on about the ambitious Fourteen Points peace plan he laid out for Congress at the end of World War I.

What if Wilson had had access to some of the political artillery his successors have wielded? He was a spellbinding orator, and if he had been able to address the nation using the newfangled medium called radio, he might have been able to cajole America into League membership. At least he might have avoided the exhausting trek by train that sapped him and likely brought on his stroke. But his first and only radio talk, marking the fifth anniversary of the World War I armistice, came in 1923, after he had left office.

His admirers like to kick around these counterfactual versions of history. What if the stroke had killed him quickly? “He would have been a martyr instead of an ineffectual political ghost, and that might have carried America into the League,” Knock conjectures.

For that matter, what if Wilson had lost the 1916 election, instead of barely squeaking back into office? His first-term accomplishments untarnished by having led the country into war and then into an ugly peace, and by his long, slow fade, he might now be recalled with greater warmth.

Well, who knows? But as the current flap raises his profile again, it appears to have produced certain beneficiaries. Every past president, after all, generates a small industry. Once Beck started mentioning Ronald Pestritto’s book, for instance, “paperback sales really shot through the roof,” at least by academic standards, the pleased author says. At the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library and Museum in Staunton, Virginia, where Wilson was born in a handsome brick house on a hill, visitorship has grown 12 percent in the past year.

In Washington, D.C., the Woodrow Wilson House, the Georgian Revival home where Wilson lived after leaving office and where he died, is prospering, too. “We’ve been doing very well for the last few years,” says its director.

“You know, no controversy is entirely bad.”

Paula Span, a former Washington Post reporter, teaches at the Columbia University School of Journalism and blogs for the New York Times.

Featured Article

Woodrow Wilson’s ‘Big Lie’: 17 Months Without a President

After Woodrow Wilson’s stroke, his wife and doctor ran the country

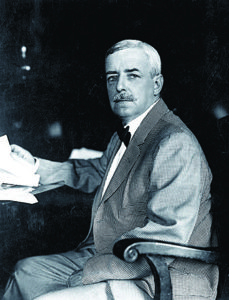

AT 11 A.M. ON MONDAY, October 6, 1919, a grim Secretary of State Robert Lansing gazed across the table at nine men seated in the White House Cabinet Room. The members of President Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet had come, at Lansing’s call, to an unprecedented meeting. Historically, the cabinet did not convene without the president’s approval. However, circumstances demanded action, and no department head had balked. The president’s chair, at the head of the table, remained empty.

Four days earlier, Wilson had “taken ill,” as the newspapers were phrasing it, and since then had been incommunicado. Washington is a rumor factory, and the capital was jittering with dark talk. No one knew if Woodrow Wilson ever again could do the job voters twice had elected him to do. Lansing, who had not seen his boss since early September, suspected the worst about the president’s condition. Lansing thought the cabinet should squarely face a topic that days earlier would have been unthinkable—transferring power from a disabled president.

For the cabinet, Lansing, 54, had two questions: who was to decide if the president was disabled, and, if so, should the cabinet, which so far had done nothing, run the executive branch in Wilson’s absence? Lansing suggested that Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, who was elsewhere in Washington that day, might have to fill the void.

The official cabinet meeting answered neither question. Ending the session but requesting that his fellow secretaries remain, Lansing summoned Dr. Cary T. Grayson, the president’s personal physician. Lansing and colleagues pressed Grayson for details on his patient’s condition. Genially sidestepping, the doctor painted Wilson in rosy tones. The president’s mind was “not only clear but very active,” the doctor declared. All that was afflicting Woodrow Wilson, Grayson claimed, was a touch of indigestion and “a depleted nervous system.”

Lansing, an attorney who had served Wilson through the recent world war and during the peace talks at Versailles, knew when he was being snowed. Grayson, 40, had made Lansing’s antennae vibrate by “carefully avoiding giving any definite information,” Lansing wrote later. However, the secretary of state had no concrete information with which to challenge the medical practitioner, who protested that Lansing lacked authority to call a cabinet meeting without the chief executive’s knowledge.

The awkward two-hour meeting ended in a whimper, with Secretary of War Newton D. Baker assuring Grayson that the cabinet had been meeting innocently to address unfinished business. Baker asked the physician to convey the cabinet’s best wishes to Wilson.

Not knowing Wilson’s condition or prognosis, the cabinet—and the entire nation—spent the next 17 months paddling in a sea of hearsay, whispers, and speculation.

Only Grayson and, more importantly, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, the president’s second wife, were regularly in the ailing Woodrow Wilson’s company and privy to his true condition, but neither was forthcoming.

For a year and a half, the United States of America operated under an unelected shadow government of two.

Born in Virginia in 1856, Thomas Woodrow Wilson rose to prominence first as president of Princeton University and then as New Jersey’s governor. A Democrat, he wore the cloak of progressive reform when he campaigned for the presidency in 1912, defeating Republican William Howard Taft and Bull-Moose candidate Theodore Roosevelt.

Standing 5’11” at 170 pounds, Wilson, 62, looked statesmanly and fit, but his health was far from robust. He had suffered strokes in 1896 and 1906, and endured bouts with chronic headaches and hypertension.

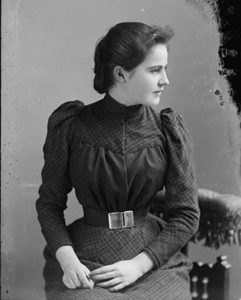

In his first term, Wilson helped create the federal reserve banking system and sent the U.S. Army to chase Mexican outlaw Pancho Villa. His wife, Ellen, died on August 6, 1914, leaving him despondent. Within a year, however, the president fell head over heels for Edith Bolling Galt, a well-to-do 42-year-old widow and the first woman in the capital to drive her own car. A whirlwind courtship ensued, and on December 18, 1915, the couple wed. The two doted on each other for the rest of Wilson’s life.

In August 1914, Europe went to war. Amid debate over whether the United States should join the fight, Wilson firmly advocated that the country be “neutral in fact as well as in name during these days that are to try men’s souls.”

In 1916, running for reelection on the slogan “He Kept Us Out Of War,” Wilson narrowly defeated Republican challenger Charles Evans Hughes.

Neutrality became untenable in 1917, as Germany waged unrestricted submarine warfare and sought to egg Mexico on to attack the southwestern United States. On April 2, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. “Neutrality is no longer feasible or desirable where the peace of the world is involved and the freedom of its peoples…” Wilson told Congress. The nation mobilized and sent two million doughboys and Marines to France to join French and British forces in a final push that defeated the Kaiser.

A November 11, 1918, armistice ended the fighting, but Wilson had a new cause. He envisioned an international body empowered to resolve multinational disputes peacefully. Wilson saw the proposed League of Nations “as the organized moral force of men throughout the world, and that whenever or wherever wrong and aggression are planned or contemplated, this searching light of conscience will be turned upon them…” The vehicle for creating the League, the Treaty of Versailles, faced formidable opposition in the United States, which would join the League only if the Senate ratified the treaty with a two-thirds vote.

Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Massachusetts) was leading the opposition, whose main objection to the treaty was a provision stipulating that an attack on any League member would, Lodge said, bring a military response from member nations. “I must think of the United States first,” Lodge said, characterizing the League as a threat to American sovereignty that would dilute the express power assigned Congress to declare war. The mutual-aid provision risked “plunging the United States into every controversy and conflict on the face of the globe,” Lodge feared.

Wilson made the League a personal crusade. Despite headaches and high blood pressure, he decided that he would take his case to the people. On September 3, 1919, a determined but weary Wilson embarked on a four-week tour of western states with speeches scheduled in 29 cities. “I know that I am at the end of my tether,” he told Joseph P. Tumulty, his secretary—a position analogous to today’s presidential chief of staff. “Even though, in my condition, it might mean the giving up of my life, I will gladly make the sacrifice to save the treaty.” Train travel was punishing and speeches taxing—in those sketchily electrified days, orators often had only their lungs for amplification.

On Thursday, September 25, Wilson was addressing a crowd in Pueblo, Colorado, when he began having difficulty speaking and maintaining his train of thought. Alarmed, his wife and Grayson persuaded him to cancel his grueling tour and return to Washington. At the White House the following Thursday morning, October 2, Wilson was sitting on the toilet when he tumbled to the floor, striking his head on the bathtub. A blocked cerebral artery had caused a stroke. The clot paralyzed Wilson’s left side, diminished his vision, restricted his speech, and impaired his judgment. The White House staff lifted him into bed. Later that day, to White House usher Ike Hoover the president “looked as if he were dead,” Hoover wrote in a later memoir. “There was not a sign of life.”

On October 3, newspapers reported that Wilson was ill and, while recovering, had to “divorce his mind from his executive duties,” but offered few details. The same day, Lansing braced Tumulty, demanding information. The president’s secretary admitted that Wilson was in bad shape; Tumulty pointed ominously to his own left side, suggesting that Wilson had suffered a paralyzing stroke. Lansing told Tumulty and Grayson that if Wilson was disabled, the president must step aside and hand responsibility to Vice President Marshall. The other two men erupted.

On October 3, newspapers reported that Wilson was ill and, while recovering, had to “divorce his mind from his executive duties,” but offered few details. The same day, Lansing braced Tumulty, demanding information. The president’s secretary admitted that Wilson was in bad shape; Tumulty pointed ominously to his own left side, suggesting that Wilson had suffered a paralyzing stroke. Lansing told Tumulty and Grayson that if Wilson was disabled, the president must step aside and hand responsibility to Vice President Marshall. The other two men erupted.

“You may rest assured that while Woodrow Wilson is lying in the White House on the broad of his back,” Tumulty roared, “I will not be a party to ousting him!” Tumulty and Grayson vowed to deny that the president was disabled. Lansing called a cabinet meeting for October 6.

Edith Wilson raised the topic of her husband resigning with Dr. Francis X. Dercum, another of Wilson’s doctors. Dercum advised her, she later claimed, that, were the president to resign, he would lose “the greatest incentive to recovery.” A reduced Wilson could do more good “with even a maimed body than anyone else,” Dercum said.

Marshall, 65, had been Indiana’s governor; his folksy style hid a shrewd political mind, and through the crisis he stayed out of sight. Best known for quipping that “what this country needs is a really good five-cent cigar,” Marshall, fearing to show the ambitions of a “usurper,” decided the only way he would step in would be if Congress were to declare Wilson incapacitated and then only if Edith Wilson and Grayson went along. Privately, Marshall complained that Wilson’s caregivers were keeping him in the dark. The Constitution prescribed no method for removing a disabled president. The decision rested with the incumbent, and the incumbent Wilson showed no desire to step aside.

Collaborating with Grayson to hide how low the stroke had laid her husband, Edith Wilson interposed an invisible but impenetrable barrier between the world and the president. All business that was intended for Woodrow Wilson went through his wife, who withheld anything, even the daily papers, that she feared might trouble him. The doctors had warned Edith Wilson that agitating her husband with upsetting information would be like “turning a knife in an open wound.” Standing by her man, Edith Wilson fended off Lansing and other cabinet members. Even when Marshall paid a get-well call, she turned him away.

The president could not be kept out of sight. By chance, Belgium’s King Albert I and Queen Elisabeth were traveling in the United States. Customarily, visiting heads of state called at the White House. Edith Wilson and Dr. Grayson carefully orchestrated an October 30 audience. A bearded Wilson—he had not shaved for four weeks—received the royals propped up in bed, curtains drawn and room dim. A blanket covered the president’s useless left arm, and staff seated the Belgians to his right, within his limited field of vision. Grayson and Edith Wilson stood by, ready to intervene, but for the duration of the 15-minute encounter Wilson was able to converse. The press reported the visit in a positive light, and the story made the front pages.

Obtaining any presidential action became a chore. Tumulty proved a bottleneck, prompting Wilson’s aides to inundate Grayson with memoranda and requests for action. The physician dutifully relayed these to Edith Wilson, but no one was ever sure if a response would follow.

Grayson flooded the press with Pollyannaish effusions regarding the president’s condition and “recovery.” He knew he was lying, he said later, blaming Edith Wilson’s powerful desire to hide the truth about her husband. Grayson’s bulletins met with skepticism, and Americans sensed something seriously amiss. Rumors multiplied that the president had gone insane, had contracted syphilis, was running naked through the Executive Mansion. Well-meaning citizens bombarded the White House by letter to suggest cures ranging from dandelion wine to Racahant, a concoction of arrowroot and cocoa, to a regime called the Bio-Dynamo-Chromatic System of Diagnosis.

Nearly a century later, it still is not clear how much power Edith Wilson wielded during the 17 months that she referred to as “my stewardship.” Wilson’s wife said she tried only “to digest and present in tabloid form” the matters she thought important enough go to the president and denied making “a single decision regarding the disposition of public affairs,” but admitted that she—and she alone—judged what the president would see. How did she do that? “I just decided,” Edith Wilson said later. “I had talked to him so much that I knew pretty well what he thought of things.” Her agenda was personal, not political. “I am not thinking of the country now,” she told one group of would-be visitors as she rebuffed them. “I am thinking of my husband.”

Instructions and orders to cabinet members came from the president’s wife, no one knowing whether they had originated with her or with the president himself. When David F. Houston was named secretary of the Treasury, Edith Wilson, not the president, interviewed Houston and gave him the good news. Memoranda to the president were returned with notes in Edith Wilson’s handwriting, and messages to the State Department were sent under her name.

Matters grew embarrassing on December 5, 1919, when Secretary of State Lansing was forced to admit before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that he had neither seen nor spoken to the president since September. To head off a congressional inquiry into Wilson’s capacity to govern, presidential aides arranged a meeting between their boss and Sen. Albert B. Fall (R-New Mexico), with whom Wilson frequently sparred, and Sen. Gilbert M. Hitchcock (D-Nebraska). A now clean-shaven Wilson received the Foreign Relations Committee members propped up in bed and flashing signs of his characteristic wit. When Fall told the president he was praying for him, Wilson asked, “Which way, Senator?” However, the visit may not have been a true test of Wilson; during the 40-minute interaction, Fall did most of the talking. The meeting made the front pages.

The entire situation disgusted Lansing. “It is not Woodrow Wilson but the president of the United States who is ill,” he wrote at the time. “His family and his physicians have no right to shroud the whole affair in mystery as they have done.” In February 1920, Lansing was forced to resign because of the cabinet meeting he had called four months earlier. By letter, Wilson belatedly but sternly rebuked Lansing. “[N]o one but the president has the right to summon the heads of the executive departments into conference,” Woodrow Wilson declared, accusing Lansing of the “assumption of presidential authority.”

The extent of Wilson’s disability will never be known, but there is little doubt that he was severely compromised. Sen. George H. Moses (R-New Hampshire) wrote to a friend that the president was “absolutely unable to undergo any experience which requires concentration of mind” and predicted that Wilson would never again be a “material force or factor in anything.”

White House usher Ike Hoover, who had seen Wilson nearly every day for eight years, noted that the president “did grow better, but that is not saying much…There was never a moment during all that time when he was more than a shadow of his former self.” Wilson could “articulate but indistinctly and think but feebly,” Hoover said. Not until March 3, 1920, was the president able to ride in an auto, even as a passenger—and minders shooed photographers before they were able to take pictures of Wilson.

On April 14, 1920, a post-stroke Wilson met with his cabinet. The sight of him shocked Treasury Secretary Houston, who had had last seen Wilson in September. The president “looked old, worn, and haggard. It was enough to make one weep to look at him.” During the cabinet meeting, Houston said, Wilson had “difficulty in fixing his mind on what we were discussing.”

Wilson never believed himself disabled, and even after his stroke toyed with the idea of a third term.

The lack of a fully functioning president became more and more noticeable. In November 1919, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and sidekick J. Edgar Hoover began rounding up suspected communists on shaky evidence, but there is no indication that Wilson knew of or approved the so-called Palmer raids. On December 2, 1919, the date set for Wilson’s annual message to Congress, the president did not appear, a first. Instead, he sent lackluster remarks Tumulty had written. “I confess I didn’t see any trace of the president in the message,” said House Speaker Frederick H. Gillett (R-Massachusetts), “and I think that is a compliment to the president.” Twenty-eight bills became law without Wilson’s signature or even his attention, and he did not address Congress in December 1920, either.

The biggest impact was on United States entry into the League of Nations. Compromise seemed possible by amending the Versailles Treaty to emphasize that war powers rested with Congress, not the League. Wilson’s supporters tried for a deal; even his wife begged him to compromise and “get this awful thing settled.” The president wouldn’t budge. On March 19, 1920, the treaty—and American entry into the League of Nations—went down to defeat in the Senate. The blow staggered Wilson. He went into a depression, Grayson said, claiming the president complained of feeling “so weak and useless.” However, after Wilson left office he did come to grips with the defeat of the League.

“Do not fear about the things we have fought for,” he told a friend. “They are sure to prevail. They are only delayed.”

Dr. Edwin A. Weinstein, a neuropsychiatrist and Wilson biographer, believed Wilson’s stroke was directly responsible for the treaty’s defeat. “It is almost certain that had Wilson not been so afflicted, his political skills and his facility with language would have bridged the gap” to a compromise, Weinstein said. While never recognizing the degree of his impairment, Wilson seemed to agree, musing to Tumulty, “If I only could have remained well long enough to have convinced the people that the League of Nations was their real hope…”

Wilson completed his term, leaving office on March 4, 1921, and three years later dying of heart disease with his wife and the faithful Grayson at his side. Wilson’s last 17 months in office echoed for years. His cherished League could not prevent a second, epochal world war—though at conflict’s end his dreamed-of entity to mediate international disputes took concrete form as the United Nations, with the United States a charter member. The UN stood, said the late president’s friend and advisor Bernard Baruch, on “the foundations laid with pain and sacrifice by Wilson.” ✯

This story was written by Joseph Connor and originally published in the June 2017 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.

Featured Article

Woodrow Wilson at War, Woodrow Wilson in Love

How an idealist distracted by romance confronted hard reality and emerged as a prophet before his time.

WOODROW WILSON LEARNED THE GRIM NEWS of May 7, 1915, before he read it in the papers, but the full-banner headlines about the German attack on a British ocean liner framed his predicament. “Lusitania Sunk by a Submarine; Twice Torpedoed Off Irish Coast,” the New York Times blared. “Washington Believes That a Grave Crisis Is at Hand.” The New York World highlighted the American connection to the liner: “Two Torpedoes Sink Lusitania; Many Americans Among 1,446 Lost.” The World added: “President, Stunned, in Seclusion.”

The president was indeed stunned. A high-minded intellectual and idealist who had been elected on promises of domestic progressivism, Wilson was suddenly forced to confront brutally real foreign policy issues. For nine months, he had kept the United States out of World War I. Now, with the death of 144 Americans, the war was pressing closer to American shores. The Lusitania crisis was the first major test of Wilson’s judgment, concentration and nerve. In dealing with the crisis, he emerged as a war leader—something he never imagined—and a prophet before his time.

At the outset, Wilson knew he must respond sternly to the German U-boat attack. The question was, how sternly? He didn’t want to ask Congress for a war declaration, and he knew that most Americans didn’t want him to either. For a century, the United States had remained aloof from Europe’s troubles, and prospered. Now the country was on a precipice, and he had to step carefully. The world watched to see how he would perform under pressure and what sort of president he would prove to be.

What the world did not know was that Wilson was also laboring under a form of pressure familiar to millions of ordinary people but rare for sitting presidents. He was head over heels in love. His mind was spinning with thoughts of the woman he was wooing and wanted to marry. Try as he might to focus on the Lusitania crisis, Wilson couldn’t help thinking of Edith. He knew cool judgment was required at this fraught moment, but with his passions running hot, cool judgment came hard.

WILSON HAD NOT EXPECTED TO DEAL WITH either war or romantic passion during his presidency. “It would be the irony of fate if my administration had to deal chiefly with foreign affairs,” he said just after his election in 1912. During his first year he concentrated on tax reform, monetary policy and antitrust regulation, and he enjoyed striking success. The Federal Reserve System was established to manage the money system. The Federal Trade Commission was created to police unfair business practices. And the 1913 Revenue Act slashed the tariff and replaced it, in part, with a federal income tax.

But as Wilson was getting ready to lead the Democrats triumphantly into the midterm elections of 1914, a terrorist killed the Austrian archduke and triggered Europe’s first continentwide war in a century. Wilson responded by proclaiming U.S. neutrality, a policy that received broad approval and allowed the war-induced demand for commodities and finished products to boost prices, wages and profits nationwide. Neutrality was good for American business, and few were eager to disrupt it.

Meanwhile, though, Wilson was struggling with a personal tragedy. When he first took office, he was contentedly married. His wife of 27 years, Ellen Axson, had given him three daughters and all the support an ambitious man could ask. But in their first year in the White House she developed kidney disease and suffered a bad fall. Complications culminated in Ellen’s death in August 1914, just as Europe was erupting into war.

Wilson was devastated. “Oh, my God!” he lamented. “What am I to do?” He was a devout Presbyterian, but Ellen’s death tested his faith. Friends and associates who admired his self-discipline were astonished to see him sob uncontrollably at the funeral. “A sadder picture, no one could imagine,” observed Cary Grayson, a Navy surgeon who served as the Wilson family physician. “A great man with his heart torn out.”

Wilson’s distress worried and then alarmed those around him. Edward House, an informal adviser who was the president’s chief confidant, recorded his growing concern in his diary. After one dinner with Wilson, House noted, “His face became grey and he looked positively sick. I was unable to lift him out of this depression before bedtime. He said he was broken in spirit by Mrs. Wilson’s death, and was not fit to be President because he did not think straight any longer.” During a visit to New York, Wilson took a long walk with House after dark. “When we reached home,” House wrote in his diary, “he began to tell me how lonely and sad his life was since Mrs. Wilson’s death, and he could not help wishing when we were out tonight that someone would kill him.”

Relief from his gloom came in February 1915, when Wilson was riding in a car with Grayson down Connecticut Avenue in Washington. Grayson waved at a female acquaintance on the sidewalk. “Who is that beautiful lady?” Wilson asked. She was Edith Bolling Galt, a widow who ran her deceased husband’s jewelry business, drove her own car—the first woman in Washington to do so—and circulated among the salons of Dupont Circle.

Grayson, encouraged by this spark in his depressed patient and friend, arranged an introduction in March. Wilson found Edith captivating. She was intelligent, informed and eager to hear everything he had to say about himself, his work and his aims for the country. Their first meetings were private, but they soon began appearing in public together. He thought everything she did was delightful. He still thought so two months later as the Lusitania crisis unfolded. In a note penned on May 9, two days after a German U-boat sank the liner, Wilson told Edith: “I need you as a boy needs his sweetheart and a strong man his helpmate and heart’s comrade.”

FROM THE START OF THE WAR WILSON AND HIS advisers had interpreted the principle of neutral rights as protecting American ships and their cargoes from attacks by either side. The British were the more serious violators at first, clamping a blockade on Germany and declaring as contraband almost anything that assisted the German war effort, including foodstuffs. The British halted and boarded American ships, forced them into British and French ports and seized their cargoes. The Wilson administration protested.

The anti-British feeling about the blockade, however, was nothing like the public storm that followed the sinking of the Lusitania. The British violated property rights; the Germans massacred innocent people. Reports, later proved true, that the Lusitania was secretly carrying munitions did little to soften the anti-German outrage. Nor were critics mollified by the news that the German government had warned passengers that the ship would be entering a war zone.

Popular and editorial demands for an energetic response created friction within Wilson’s inner circle. “America has come to a parting of the ways, when she must determine whether she stands for civilized or uncivilized warfare,” Edward House told Wilson. “We can no longer remain neutral spectators.” But Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan urged the president to move cautiously. He recommended that Americans be kept out of harm’s path, if necessary forbidding them by law to travel on ships carrying munitions. And he reminded Wilson that Britain violated American neutral rights more often, if less lethally, than Germany.

Wilson sympathized with Bryan’s desire to protect the nation from the maelstrom in Europe, and he hoped to tamp down the rising war fever. On a trip to Philadelphia he tested one pacifist message in a speech. “Americans must have a consciousness different from the consciousness of every other nation in the world,” he said. “There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right.”

The trial balloon sank almost as soon as the words left his mouth. Even commentators supportive of peace wondered what it meant to be “too proud to fight.” More than a hundred Americans were dead as a result of German ruthlessness: Was this the best the president had to offer?

Wilson quickly realized he had erred. “I have a bad habit of thinking out loud,” he admitted confidentially. “That thought occurred to me while I was speaking, and I let it out. I should have kept it in.” Publicly, he backtracked: “I was expressing a personal attitude, that was all.”

What Wilson declined to share with the public was why his judgment had faltered. He was utterly distracted by his budding romance. Thoughts of Edith filled his head. He saw her two or three times a day, despite the demands of his presidential schedule, and he sent her cards and notes frequently. In one message he attributed his fumble in Philadelphia to his infatuation, writing: “My heart was in such a whirl from that wonderful interview of yesterday and the poignant appeal and sweetness of the little note you left with me.”

WHEN HE REGAINED HIS COMPOSURE, WILSON sent a message to the German government condemning the Lusitania sinking as illegal and barbarous. A passenger ship had been torpedoed “without so much as a challenge or a warning,” he wrote, and “a thousand souls who had no part or lot in the conduct of the war…were sent to their death in circumstances unparalleled in modern warfare.” The American deaths were a special concern, he went on, but the principle involved was larger than this, or any other, incident. “The Government of the United States is contending for something much greater than mere rights of property or privileges of commerce. It is contending for nothing less high and sacred than the rights of humanity.” Wilson concluded his note by demanding that Germany change its submarine policy and offer guarantees that attacks on civilian vessels like the Lusitania would not recur.

The German government equivocated. It cited the difficulties of waging war at sea, and it pushed the blame on Britain for loading weapons on passenger ships.

Wilson rejected the German response and dispatched a second note that sharpened the American position. British actions had nothing to do with the present case, he said. Killing civilians from a neutral country was “illegal,” “inhuman” and “manifestly indefensible.” If Germany persisted with its naval policies, the United States government would interpret such a course as “deliberately unfriendly.” Wilson’s words suggested that another sinking could bring the United States into the conflict on the side of Germany’s foes.

This was what Bryan feared. The secretary of state argued against pushing Germany into a corner. At the least, he argued, the president should balance his demands of Germany with criticism of the British for their violations of American neutral rights.

Wilson refused to alter his stance, but he did his best to placate Bryan. “You always have such weight of reason, as well as such high motives, behind what you urge that it is with deep misgiving that I turn from what you press upon me,” he told Bryan.

Bryan was not appeased. The president’s path was dangerous, he reasserted. He complained, as well, that Wilson was paying more attention to Edward House, a mere private citizen, than to him, the secretary of state. “Colonel House has been secretary of state, not I,” Bryan said to Wilson. “I have never had your full confidence.”

Wilson couldn’t deny the truth of Bryan’s remark. But he wouldn’t change his policy, and, as matters proved, he couldn’t change Bryan’s mind. Bryan quit.

WHILE WILSON’S FIRM POLICY TOWARD BERLIN cost him his secretary of state, it bought him time with Germany. The German government ordered its submarine commanders not to target passenger vessels. At first this order was secret, but after one U-boat captain violated it and torpedoed the British liner Arabic, killing two Americans and two score others, the German ambassador to the United States revealed the orders lest the latest incident further inflame American feeling.

Germany’s retreat enabled Wilson to keep the United States out of the European bloodbath for another 18 months. During that time he campaigned for a second term on the slogan “He kept us out of war,” and was reelected. A reluctant realist when it came to the military conflict, Wilson tried to organize a peace conference, and broached the concepts of “peace without victory” and a “League of Peace”—an international body with the power to enforce good behavior among nations.

But he couldn’t stop the war, or keep his nation out of it. In early 1917, the German government, desperate to break the deadlock on the western front, declared a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. German U-boats began sinking American vessels. Wilson responded by making good on his earlier threat: In April 1917 he asked Congress for a war declaration, and Congress approved.

By then Wilson was fully focused on the grave matters of state. He’d resolved his crisis of the heart more than a year earlier, in December 1915, when he married Edith in a private ceremony at her home. Some of his advisers had recommended postponing the wedding but Wilson wouldn’t hear of delay. Perhaps he knew that he’d never be able to concentrate on his job until Edith was his wife.

THE WAR WENT WELL FOR THE UNITED STATES, but the peace proved complicated. Wilson led the country to victory and then headed the American delegation at the Paris Peace Conference. He cajoled U.S. allies into accepting the League of Nations as an instrument for preventing another war, but many Americans resisted the compromise of sovereignty that membership would entail. Wilson toured the country generating support for the peace treaty and the League, and his efforts appeared to be paying off until he suffered a stroke that largely incapacitated him for the rest of his presidency.

He might have resigned had the public understood the gravity of his condition. But Edith Wilson kept all but his closest advisers away. She carried messages into his sickroom and brought decisions out. No one could tell whether the decisions were his or hers. Edith doubtless saw little distinction. Since the Lusitania crisis he had confided all his important decisions to her; she confidently judged she knew his mind as well as he did.

But she—or he—didn’t know the mind of the Senate, which rejected the peace treaty and the League. Wilson left office a broken man. By his death in 1924 the United States had turned isolationist—irretrievably so, it seemed. Yet harsh reality eventually proved this idealist right, for when fascism enveloped the world in a second cataclysmic war, Americans belatedly came to appreciate Wilson’s wisdom. Their government’s 1945 sponsorship of the United Nations, an updated version of his League, was a posthumous nod to his prescient internationalist vision.

H.W. Brands’ most recent book is The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses Grant in War and Peace.

Originally published in the June 2013 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.