In February 1942, days after a Japanese submarine shelled the California coast, anti-aircraft gunners in Los Angeles engaged a far more insidious and elusive foe.

A few minutes after 7 p.m. on Feb.23, 1942, twilight was settling over the sleepy, seaside town of Goleta, 10 miles north of Santa Barbara. Most Californians—like their fellow citizens across the country—were gathered around their radios. President Franklin Roosevelt had begun his latest “fireside chat” broadcast, the first since the U.S. declaration of war

on Japan nearly 11 weeks earlier.

Though the attack on Pearl Harbor had sparked fears of a full-scale Japanese assault on the West Coast, nothing had materialized. Early in his speech Roosevelt emphasized that America was engaged in “a new kind of war…different from all other wars of the past, not only in its methods and weapons but also in its geography.” The president asked listeners to spread a map of the world before them so they could follow his references to the “world-encircling battle lines” of the conflict into which the United States had been drawn.

Warming to his subject, Roosevelt then said something Californians would soon find eerily prescient: “The broad oceans which have been heralded in the past as our protection from attack have become endless battlefields on which we are constantly being challenged by our enemies.”

Even as the president spoke, sailors of the same navy responsible for the devastating surprise assault on the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Hawaii were preparing to launch the first direct attack by a sovereign nation on the American mainland since the War of 1812.

And the sleepy coast of California would be the target.

On Feb. 1, 1942, two American aircraft carrier task forces carried out aerial attacks and naval gunfire bombardments on Japanese ships and shore installations in the Gilbert and Marshall islands, some 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii. While the attack caused only moderate damage, it came as a complete surprise to the Japanese and was a rude reminder that despite its losses at Pearl Harbor the U.S. Navy could still lash out across the Pacific.

On Feb. 1, 1942, two American aircraft carrier task forces carried out aerial attacks and naval gunfire bombardments on Japanese ships and shore installations in the Gilbert and Marshall islands, some 2,500 miles southwest of Hawaii. While the attack caused only moderate damage, it came as a complete surprise to the Japanese and was a rude reminder that despite its losses at Pearl Harbor the U.S. Navy could still lash out across the Pacific.

Among those wounded during the American attacks was Vice Adm. Mitsumi Shimizu, who commanded Japan’s submarine force from his flagship, the light cruiser Katori, based at Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshalls. Soon after the U.S. assault he ordered several subs to give chase and then patrol the area south of Hawaii, hoping to ambush the American raiders as they returned to Pearl Harbor. On February 7 Shimizu directed one of the patrolling boats, Commander Kozo Nishino’s I-17, to detach from the group and head for the California coast. Nishino’s mission was to target American shore installations.

I-17 and its captain were ideally suited to the mission.

Launched in 1939, the vessel was a large, long-range Type B1 cruiser submarine (see P. 20) capable of traveling 16,000 miles without refueling. In addition to 17 torpedoes, a 5.5-inch deck gun and twin 25 mm anti-aircraft guns, I-17 was fitted with a waterproof hangar that housed a catapult-launched E14Y1 floatplane. Larger and arguably more capable than contemporary American subs, the Type B1 was a well-built and highly effective predator.

At I-17’s helm was a skilled and experienced captain. A career naval officer, Nishino was a graduate of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s submarine school. Before the war he had commanded a tanker that regularly hauled oil from California to Japan, and he had visited ports from San Francisco to San Diego. Believing the latter offered the greatest number of targets, Nishino set a course for southern California and arrived off Point Loma on February 20. The following night, as the submarine cruised on the surface to recharge its batteries, its lookouts spotted what appeared to be an enemy patrol boat. Nishino changed course and increased speed but was finally forced to submerge when it appeared the unidentified vessel was following the sub.

On the morning of February 22, as Nishino pondered the wisdom of remaining in the heavily trafficked seas off San Diego, he received a radio message from Shimizu on Kwajalein directing I-17 to shell a shore target of his choice in order to stir panic along the West Coast. After considering several possibilities, Nishino settled on an area he knew well: the Ellwood Oil Field, a few miles west of Goleta. According to California historian and author Justin Ruhge, during his days as a tanker captain the Japanese officer had repeatedly stopped at the Ellwood installation to refuel and take on oil. As a guest of the Barnsdall–Rio Grande Oil Co. he had frequented the local Wheeler Inn café.

This visit, however, would not be as sociable.

By dawn on February 23 the submerged I-17 was entering the west end of the Santa Barbara Channel, the roughly 28-mile-wide, 80-mile-long body of water separating the California coast from the four northernmost Channel Islands. Through his periscope Nishino sighted several oil storage tanks and what he believed to be the refinery. Then he submerged and waited out the daylight. At dusk I-17 surfaced and moved inshore, coming to a stop some 4,000 yards off the beach as Nishino prepared his crew for action.

At 7.15 p.m., despite diminished visibility in the darkness and haze, Nishino ordered I-17’s deck gun crew to send seven armor-piercing rounds whistling toward the storage tanks. After landing what they believed to be several solid hits—despite no visible fire or damage—the gunners shifted their aim and lobbed an additional 10 rounds at the presumed refinery. While the exploding shells produced no secondary explosions or gouts of oily flame, Nishino and his bridge crew were convinced they’d inflicted serious damage on the oil facility. At 7:35, after seeing car lights ashore and hearing the dim warble of a siren, the Japanese captain ordered his gunners to cease fire and got his vessel under way. About an hour later several witnesses spotted the surfaced I-17 exiting the east end of the channel. Three aircraft and two destroyers gave chase but failed to locate the submarine.

On reaching the open sea, I-17 circled back north, its captain intending to hunt for targets off San Francisco. By the time the submarine set out on the return trip to Japan on March 12 Nishino had attacked—and reported to have sunk—two American ships.

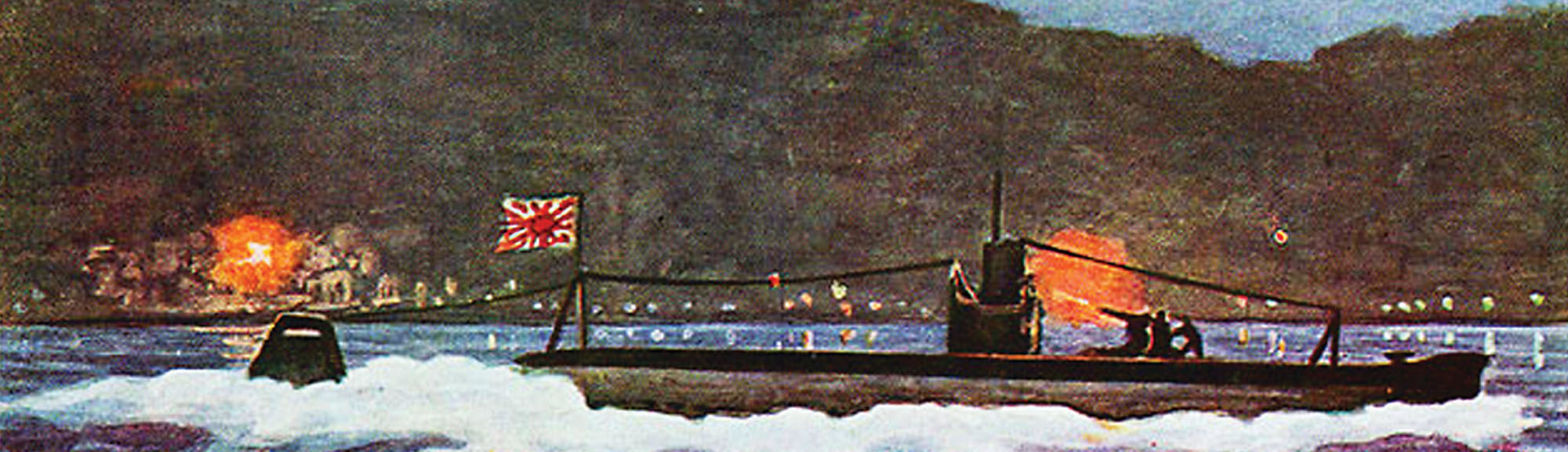

Tallying those presumed victories alongside what Nishino reported as severe damage to the Ellwood oil facilities, I-17’s California cruise seemed to have been a great success. Indeed, on the sub’s March 30 arrival at Japan’s sprawling Yokosuka naval base the captain and his men were hailed as the heroes of what was portrayed as a daring and almost suicidal mission. Japanese newspapers nationwide lauded the first attack on the U.S. mainland, and to boost morale, printers issued millions of commemorative postcards depicting the shelling of the California coastline.

While the propaganda value of I-17’s patrol dissolved in the wake of the April 18 raid on Tokyo and environs by a flight of 16 carrier-launched U.S. Army Air Forces B-25B bombers led by Lt. Col. James Doolittle, Nishino and his crew continued to believe they had struck a mighty blow against America and caused widespread panic up and down the West Coast.

As it turned out, they were only half right.

Although I-17’s shelling of the Ellwood oil installation was an undeniably bold act, from a tactical point of view it was a complete waste of ammunition. The attack caused no casualties, and most shells fired by the sub’s deck gunners fell short of their intended targets, dropping into the sea, onto the beach or impacting atop nearby cliffs or in empty fields. Those few rounds that actually hit something did an estimated $500 worth of damage, primarily to a small derrick, a solitary pump house and a catwalk at the Barnsdall–Rio Grande facility. Aside from the handful of warplanes and pair of destroyers dispatched to hunt for the retiring I-17, the attack had failed to draw off further military resources or compel the U.S. Navy to recall what remained of the Pacific Fleet to protect the West Coast.

But Nishino and his crew had fulfilled the second part of their mission in spectacular fashion, for their attack had sparked widespread uncertainty and fear along the Pacific coast. Residents from San Diego to the Canadian border suddenly woke to the fact the Japanese were not only entirely capable of bringing the war to America’s shores but also likely to do so without warning.

Within 24 hours of the bombardment of Ellwood that growing paranoia led to what has gone down in history as “The Great L.A. Air Raid.”

Although word of the Ellwood shelling was front-page news on Tuesday, February 24, the day was a relatively calm one for residents of greater Los Angeles—until early evening, that is. At about 7 p.m. the headquarters of the 37th Coast Artillery Brigade, at Camp Haan in Riverside, began receiving reports of flares and blinking lights in the vicinity of defense plants and oil fields along the coast. At 7:18 p.m. air raid sirens started to wail as helmeted wardens rushed to their posts countywide. When no threat materialized, authorities lifted the alert at 10:23 p.m. A few hours after midnight, however, all hell broke loose.

According to a report from Western Defense Command, at 1:44 a.m. on February 25 a coastal radar site picked up an unidentified aerial target some 120 miles west of Los Angeles. Anti-aircraft batteries throughout the region were put on high alert, their guns manned and fully loaded. At 2:15 a.m. two additional radar sites reported that the unidentified object was rapidly approaching the city, and minutes later the regional air-raid warning center ordered a total blackout. Within an hour the 37th Coast Artillery—charged with the air defense of greater Los Angeles—ordered its batteries of .50-caliber machine-guns and 3-inch anti-aircraft guns scattered across the city’s hills to open fire as targets presented themselves. Within moments the dark skies above the city were alive with stabbing searchlight beams, arcing necklaces of tracer fire and the bright bursts of exploding shells.

Pilots of the 4th Interceptor Command were put on alert, but their aircraft remained grounded. Accounts flooded in of enemy planes within a 25-mile radius of greater Los Angeles, even though the mysterious object initially tracked by radar appeared to have vanished. At 3:06 a.m. spotters reported a balloon carrying a red flare over Santa Monica, and anti-aircraft gunners redirected their fire inland.

Anne Ruhge was 9 years old and living in the beach town of Venice that chaotic night. “My mother woke me and my sister up and shouted, ‘They’re shooting!’” she recalled. “We looked out our kitchen window, and there were searchlights everywhere, and guns were firing. I remember my mom being so nervous her teeth were chattering. It was really scary. We thought it was another invasion.” Ruhge’s father was in the California National Guard and had been called out. “When he came back home, he didn’t want to talk about it. Said it was top secret.”

“I heard about the bombing in Santa Barbara, but that was a submarine attack,” recalled Robert Hecker, then a 20-year-old working for Douglas Aircraft Co. in Long Beach. “When this air raid broke out, it was a total surprise. The guns and sirens woke me up. I ran outside, but I couldn’t see any concentrated fire.” Hecker may not have seen anything, but he did hear it when a piece of flak bounced off the roof of his house.

At 7:21 a.m. the regional warning center finally sounded the all clear and lifted the blackout order. Anti-aircraft batteries had fired more than 1,400 shells that night, but no bombs had been dropped, no aircraft shot down. There were, however, five civilian casualties—three from blackout-related car accidents, two from heart attacks. Hearsay and conjecture ran rampant amid the chaos. Local media did little to assuage fears the next day with sensational, unsubstantiated headlines.

William Randolph Hearst’s Los Angeles Herald-Examiner led the charge:

AIR BATTLE RAGES OVER LOS ANGELES

One Plane Reported

Downed on Vermont

Avenue by Gunfire

Bowing to pressure, the Los Angeles Times joined the hyperbolic bandwagon:

L.A. AREA RAIDED!

Jap Planes Peril Santa Monica,

Seal Beach, El Segundo, Redondo,

Long Beach, Hermosa, Signal Hill

The Times was the only paper to send out a photographer that night and published several photos of the “raid,” including a dramatic image of the night sky lit up like the Fourth of July by searchlight beams and air bursts.

Rumor had it the sighting of an aircraft launch from a Japanese submarine had triggered the night’s events.

“My father was a manager at Vultee Aircraft,” recalled Clegg Crawford, who said shrapnel fell like rain that night in his Long Beach neighborhood. “He was called away to a crash site that night along with men from Douglas and Lockheed. He told me a seaplane from a submarine had crashed, and they were going to separate it into pieces for examination.” Postwar interviews and examination of Im-

perial Japanese Navy records have since confirmed no Japanese planes were airborne over Los Angeles at the time of the raid. It was later determined anti-aircraft gunners had mistaken drifting smoke swept by the beams of powerful searchlights for enemy aircraft.

In the aftermath of the barrage Lt. Col. John G. Murphy—the Army’s senior anti-aircraft artillery officer for the Western United States—and a board of fellow officers interrogated 60 witnesses, civilians as well as Army, Army Air Forces and Navy officers and enlisted personal. In the May-June 1949 issue of the U.S. Coast Artillery Association’s Antiaircraft Journal, Murphy wrote of the interviews:

About half the witnesses were sure they saw planes in the sky. One flier vividly described 10 planes in V formation. The other half saw nothing.

While he couldn’t account for such discrepancies, Murphy did proffer an explanation for the aberrant shelling:

The firing had been ordered by the young Air Force controller on duty at the Fighter Command operations room. Someone reported a balloon in the sky. He of course visualized a German or Japanese zeppelin. Someone tried to explain it was not that kind of balloon, but he was adamant and ordered firing to start (which he had no authority to do). Once the firing started, imagination created all kinds of targets in the sky, and everyone joined in.

The primary cause of “The Great L.A. Air Raid” did indeed turn out to be a balloon—but one launched by the city’s defenders, not the Japanese.

At about 1 a.m. on February 25, hours after the initial scare in Los Angeles, one of the 37th Coastal Artillery regiments sent up a meteorological balloon to measure wind speed and direction—vital information were its batteries to successfully engage enemy aircraft. It was that very balloon, fitted with a red flare so those on the ground could track it, that prompted anti-aircraft batteries to open fire. When the shooting settled down, gunners in a different regiment, dissatisfied with their performance, decided to glean additional data and sent up a second flare-toting balloon—and all hell again broke loose.

After the war the Los Angeles Daily News published a plausible alternative explanation from a man who had served in one of the coastal batteries:

Early in the war things were pretty scary, and the Army was setting up coastal defenses. At one of the new radar stations near Santa Monica the crew tried in vain to arrange for some planes to fly by so they could test the system. As no one could spare the planes at the time, they hit upon a novel way to test the radar. One of the guys bought a bag of nickel balloons and then filled them with hydrogen, attached metal wires and let them go. Catching the offshore breeze, the balloons had the desired effect of showing up on the screens, proving the equipment was working. But after traveling a good distance offshore and to the south, the nightly onshore breeze started to push the balloons back toward the coastal cities. The radar picked up the metal wires, and the searchlights swung automatically on the targets, looking on the screens as aircraft heading for the city. The ack-ack starting firing, and the rest was history.

Although the Japanese had had nothing to do with the “Battle of Los Angeles,” it and I-17’s shelling of the Ellwood oil facilities served to hasten the implementation of—and broaden the effects of—Executive Order 9066, which Roosevelt had signed into law on February 19. In the interest of national security the order prescribed certain areas as military zones, clearing the way for internment of any and all resident aliens, but the paranoia that erupted on the West Coast in late February ensured those of Japanese ancestry were disproportionately sent to internment camps farther inland for the duration of the war.

Back in Santa Barbara, area residents embraced the I-17 bombardment as a badge of honor, granting them boasting rights as the first American city to survive an enemy attack on the mainland in more than 200 years. The 4th Santa Barbara War Savings Committee and American Women’s Voluntary Services soon initiated an “Avenge Ellwood!” war bonds campaign, plastering its plane-shaped logo on every available surface. Funds were directed to build two warplanes—a bomber and a fighter dubbed respectively the “Flying Santa Barbaran” and “Ellwood Avenger.” Apparently, the bomber was never built, while the fighter never saw action. Today the Ellwood refinery and tanks are long gone, replaced by the Sandpiper Golf Club and exclusive Bacara Resort & Spa.

“The Great L.A. Air Raid” went on to become fodder for alien conspiracy theorists and the subject of books, documentaries and films, including Steven Spielberg’s comedy spoof 1941 and, more recently, the sci-fi war film Battle: Los Angeles. And each February the Fort MacArthur Museum in San Pedro stages an annual fund-raiser that centers on a live recreation of the air raid, enabling onlookers to step back in time and experience a little of what it was like that mysterious, terrifying night in 1942.

Liesl Bradner is a Los Angeles–based journalist and writer whose work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, World War II magazine and other publications. For further reading she recommends The Great Pacific War, by Hector C. Bywater, and The Military History of California, by Justin M. Ruhge.

First published in Military History Magazine’s November 2016 issue.