AT THE END of May 1942, the tide of war was running against the Allies. Whether it was Hitler’s Wehrmacht in Russia, Rommel’s desert army in Africa, or the U-boats of the Atlantic, Axis forces were wreaking havoc and threatening to gobble up key territory. Things looked particularly dire in the Pacific. After Pearl Harbor, Japan had seized Hong Kong, the Philippines, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies, and Burma. Imperial forces were also knocking on the door of India and Australia. Allied leaders fretted that Axis powers might soon link hands through the oil-rich Middle East.

Even the western United States looked vulnerable, particularly Hawaii. The tiny American outpost of Midway, the most far-flung atoll in the Hawaiian archipelago, lay 1,100 miles northwest of Oahu, presenting an inviting target. And it was to Midway, 70 years ago, that the Japanese sent a giant armada, and there that Americans made a heroic, if flawed, stand. The fighting raged for three days, but in the end, the battle’s outcome—indeed, the course of the war itself—turned on 10 minutes of work by a few brave American naval aviators.

WHAT WAS ARGUABLY the pivotal naval battle of World War II was set in motion by 58-year-old Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Japanese fleet. An early exponent of carrier warfare, he had helped after World War I to build Japan’s navy into the world’s most imposing and modern carrier fleet at a time when most navies were still wedded to the notion of big-gun warship supremacy.

Though he conceived and directed the raid on Pearl Harbor, Yamamoto had misgivings about a war with the United States, whose strength he knew well from his studies at Harvard and two stints as a naval attaché in Washington. “I shall run wild for the first six months or a year,” he remarked after Pearl Harbor, “but I have utterly no confidence for the second and third years of the fighting.”

Still, Yamamoto’s service as a young lieutenant in the epic 1905 Battle of Tsushima gave him what he thought might be the key to beating the United States. In that battle, the upstart Japan had destroyed the Russian navy in a single, brief encounter. The victory had put Japan on the map in world affairs and made a national hero of the Japanese fleet’s leader, Admiral Heihachiro Togo. Yamamoto, who had lost two fingers in the battle, venerated Togo. Now, facing the United States, he devised a battle plan similar to what his hero might have done. In March 1942, he proposed a twin-pronged operation to take Midway, bring out the remnants of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and then destroy it in one decisive engagement.

Yamamoto’s plan, described as “Byzantine” by one historian, entailed dividing his fleet into four main components. First to hit Midway would be Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s carrier force, the Kido Butai, biting edge of the Japanese navy, with four big fleet carriers, the Akagi, the Kaga, the Hiryu, and the Soryu. Then, once Nagumo’s bombers had softened up the Midway defenses, a transport group covered by four heavy cruisers would descend on the island and land 5,000 invasion troops.

Another battle group with four heavy cruisers and two battleships would lurk farther out. And finally, some 600 miles from Midway and at least a day’s sail away, would lie Yamamoto’s main body with three battleships. The admiral would command from the Yamato—at 72,800 tons, the biggest battleship ever built. Its 18.1-inch guns could outrange any Allied ship and sink it from 26 miles away with monster shells weighing some 3,000 pounds, more than twice the weight of the missiles the biggest American guns could throw.

As if that wasn’t enough, Yamamoto also set in motion a separate operation, sending another fleet north to invade the Aleutian Islands, part of America’s Alaska Territory. It alone mounted 3 heavy and 3 light cruisers, 12 destroyers, and 2 light carriers.

To test Yamamoto’s plan, the Japanese held battle maneuvers aboard the Yamato on May 1. But these were designed to please the commander in chief. In the war-gaming, both the Akagi and the Kaga were sunk, an unacceptable result; Yamamato’s chief of staff reversed the umpire’s decision and refloated the Akagi. The exercise was a display of what several Japanese veterans later called the “victory disease”—the refusal, after the flow of early triumphs, to contemplate even the possibility of defeat—which would distort all Japanese planning that spring.

Symbolically, the Midway operation commenced on May 27, Japan’s national day commemorating Togo’s triumph. The 200-ship fleet, the greatest Japan ever put to sea, must have presented a phenomenal spectacle as it slid out of a mist-bound Inland Sea. Earlier in the month, Japanese carriers had slugged it out with the Americans in the Coral Sea and come away with only a draw. But that had left Japan’s confidence unbowed as the armada set off to considerable pomp and circumstance.

“Everybody in the fleet from the head down to the men entertains not the least doubt about a victory,” Captain Yoshitake Miwa, the combined fleet’s air officer, wrote of this “greatest expedition” in his diary. “Whence comes such a spirit that overwhelms an enemy before the battle is fought?”

AGAINST THE DREADED KIDO BUTAI, what had the battered American Pacific Fleet to offer? Its commander, Texas-born Chester William Nimitz, came from sailing stock; his grandfather had served in the imperial German merchant marine. Nimitz, then 57, was a leading U.S. Navy authority on submarines but had little experience with carrier warfare. He was known, remarkably, for both boldness and caution; he listened to his advisers and was immune to panic. His hobby, as one historian noted, was “the homely pastime of pitching horseshoes.”

“I will be lucky to last six months,” Nimitz wrote his wife upon his appointment. “The public may demand action and results faster than I can produce.” Yet he was to shine—one of the few Allied commanders untouched by criticism.

The assets of Nimitz’s fleet were slender. The Pearl Harbor attack had left him without a single battleship, and he had only two fully operational aircraft carriers, the Enterprise and the Hornet. The latter had a largely green crew; many of the aviators had never even taken off from a carrier. A third carrier, the Yorktown, had been battered in the Coral Sea fight and limped back to Pearl Harbor, where it was being feverishly repaired.

Adding to American concerns was an unsettling last-minute change in commanders. Vice Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, Nimitz’s pugnacious carrier chief, was hospitalized with excruciating psoriasis. His replacement, Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, had never led a carrier force before.

Amid all this uncertainty, navy intelligence handed Nimitz a terrific weapon. Led by a back-room genius, Commander Joseph J. Rochefort Jr., a top-secret team had broken the Japanese naval code. From Rochefort’s intercepts Nimitz learned that a massive Japanese strike was in the offing; he knew its components and rough date but not its objective. That appeared in the Japanese code only as “AF.” The Americans suspected this stood for Midway and set up a clever ruse to prove it. They sent an uncoded message detailing a shortage of fresh water on the island. The Japanese fell into the trap, reporting in their compromised code that “AF” was low on water.

The U.S. intelligence projection of the planned attack was to prove off by only five minutes, five degrees, and five miles.

On May 15, Nimitz set his modest force in motion. Unlike Yamamoto, who rashly placed all his carriers in one basket, Nimitz divided his three among two task forces: TF 16, under Spruance, comprising the Enterprise and the Hornet; and TF 17, centered around the damaged Yorktown, with an escort of two heavy cruisers and five destroyers. Leading TF 17 was Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, the senior of the two commanders and an experienced sailor who had brought Yorktown through the Coral Sea battle. Meanwhile a small covering force was sent to Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians.

Fletcher and Spruance planned to rendezvous at a map reference optimistically code-named Point Luck, northeast of Midway. From there, they intended to ambush the left flank of Nagumo’s invading fleet. Fletcher won the first hand in the game against Yamamoto by slipping out of Pearl Harbor before Japanese submarines arrived to throw a cordon around the base to track U.S. naval movements. Indeed, Japanese reconnaissance was so poor that Yamamoto and Nagumo had no idea where the American force was nor how many carriers it contained. They still believed the Yorktown had been sunk in the Coral Sea and were unaware it was sailing toward Midway.

AT 7 A.M. ON JUNE 3, Japanese carrier planes struck Dutch Harbor and Japanese troops seized two Aleutian islands, Kiska and Attu. Though these represented the first territories in the United States proper to be taken by the enemy, they were icy, barren outposts of little strategic value. A commander less well-informed and judicious than Nimitz might have been distracted from the main attack. But he was not.

That same morning, Jack Reid, a young ensign piloting a PBY-5A Catalina flying boat on a scouting mission a thousand miles south of the Aleutians, spotted a few specks in the water. “My God, aren’t those ships on the horizon?” he shouted. “I believe we have hit the jackpot.” That sighting of the Japanese was followed by more the next morning, June 4. At 5:45, another PBY rattled off the warning: many planes heading midway.

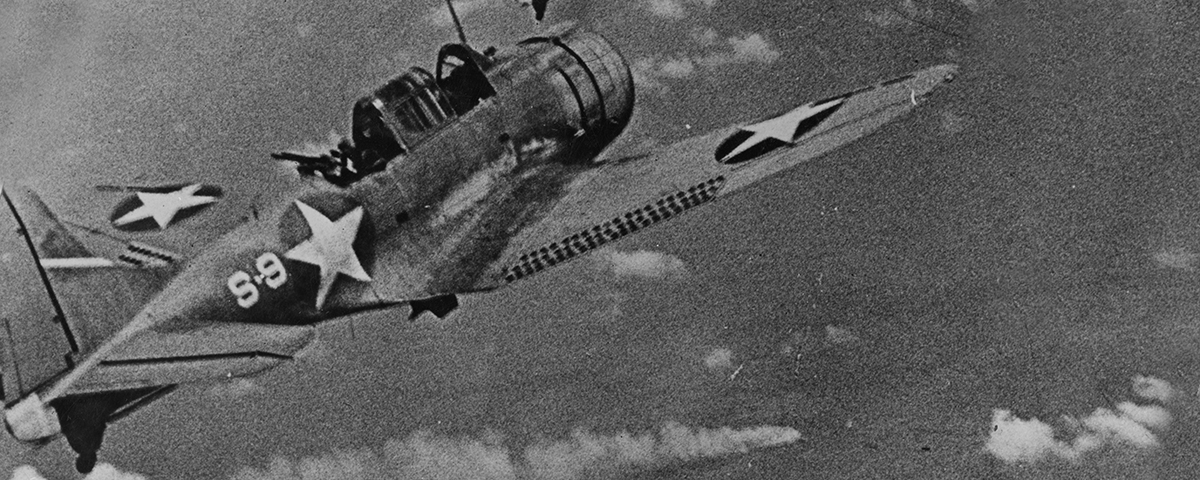

With that, the curtain went up on the battle. Bristling with defenses Nimitz had urgently reinforced, Midway at once sent aloft as many aircraft as it could, both to meet the enemy and to avoid being caught on the ground, as the air force had been at Pearl. Among the 93 operational planes on Midway that day were 15 Army Air Force Boeing B-17E Flying Fortresses and some three dozen Marine Corps aircraft—Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat and Brewster F2A-3 Buffalo fighters and Vindicator dive-bombers. The fighters were largely obsolete: peeling wood-and-fabric skin from the interwar years covered some, while others had antiquated engines that quickly failed. “Any commander that orders pilots out for combat in an F2A-3,” said one American officer, “should consider the pilot as lost before leaving the ground.”

The Japanese aviators, meanwhile, were among the war’s most experienced, having flown in their country’s battles with China, the Pearl Harbor raid, and the Battle of the Coral Sea. And they manned the best carrier fighter in the world, the deadly Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero. Extremely nimble, faster than any Allied equivalent, and with a remarkable range of 1,900 miles, the plane would be credited with shooting down more than 1,500 U.S. planes during the war.

Some Midway bombers targeted the Japanese carrier fleet, including four Martin B-26 Marauders armed with torpedoes and six Grumman TBF-1 Avenger torpedo bombers from the Hornet’s Torpedo Squadron 8 (VT-8) that had been assigned to Midway and whose crews had never before seen combat. The Japanese shrugged off these attacks, losing just a couple of fighters while destroying all but one TBF and two B-26s. And on Midway itself, they also crushed the U.S. fighter planes, leaving only two operable.

Despite this early success, Nagumo had misjudged what it would take to break down Midway’s defenses. Of the 108 planes in that first wave against Midway, only a third were dive-bombers. He held another 35 torpedo planes and dive-bombers in reserve, anticipating the big encounter with the American fleet that Yamamoto was hoping for. As a result, he failed to inflict more than ephemeral damage to the island. Midway could still easily resist any landing. Its crucial airstrip remained virtually untouched; perhaps the Japanese, confident of success, hoped to keep it safe and use it themselves.

At the same time, U.S. antiaircraft fire from the island had taken out several Japanese planes. At 7 a.m., the Japanese attack leader sent Nagumo a message: “There is need for a second attack wave.”

Though displeased, Nagumo agreed to send help. There was no sign of enemy carriers yet, so he ordered deck crews to replace the torpedoes already loaded on his planes with fragmentation bombs—an operation that would take more than a few minutes. This decision directly contradicted Yamamoto’s order to keep the reserve strike force armed for anti-ship operations. But Nagumo was somehow encouraged by this message from Yamamoto: “There is no sign that our intention has been suspected by the enemy.”

It’s difficult to say precisely when fortune threw in with the American underdogs in this fight. But Nagumo’s order, delivered at 7:15 a.m. on the first day of the battle, marks the moment when Yamamoto’s complex plan started to unravel. If any of Yamamoto’s seven battleships and heavy cruisers had been available to hammer Midway’s defenses with their massive guns, not to mention the fearsome 18.1-inch shells of the Yamato, they surely would have made quick work of the tiny atoll’s defenses—and Nagumo would not have had to decide between bombing Midway and attacking the American fleet. But under Yamamoto’s scheme, his battleships were being held in reserve, hundreds of miles away, for the reprise of Tsushima.

NIMITZ LATER REPORTED to his superior, Admiral Ernest J. King, chief of naval operations, that he believed a “great force of about 80 [Japanese] ships” was converging on Midway. Most of Midway’s fighters, torpedo planes, and dive-bombers “were gone,” he said. And despite that sacrifice of lives and planes, not a single American bomb or torpedo had yet hit a Japanese ship.

With the battle now a couple of hours old, Admiral Fletcher at Point Luck held back from committing the planes from the three U.S. carriers, which he still hoped to use to ambush the main Japanese force. But once he learned, shortly after dawn, that Nagumo’s carriers had been identified, he instantly ordered an all-out attack. He thought it essential to strike before Nagumo’s superior force could hit him. For about 90 minutes beginning at 7 a.m., the Hornet, the Enterprise, and the Yorktown launched their planes. A portent of the battle ahead, the Hornet’s inexperienced teams took an hour to get their aircraft in the air, and their planes had to circle, wasting precious fuel.

For all the U.S. intelligence advantages, the Americans did not know the precise location of Nagumo’s four carriers. Worse, led by a self-assured commander, Stanhope C. Ring, the Hornet attack group followed an incorrect heading of 265 degrees. Dubbed by historians “The Flight to Nowhere,” Ring’s raid didn’t find the Japanese carriers, and the planes returned to the Hornet with their full load of bombs.

One officer refused to follow Ring. Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron, leading VT-8, angrily insisted that the correct heading was 240. With insubordination worthy of Nelson at Copenhagen in 1801, Waldron (at 41, the oldest pilot) and his squadron broke formation. The move cost him his life and all of his squadron, save one man. Now on course, he sighted the enemy carriers and began attacking at 9:20. Waldron’s last orders: “If there is only one plane left to make the final run in, I want that man to go in and get a hit.”

Without a fighter escort, all 15 TBD Devastators of VT-8 were shot down by hordes of Zeros before they could inflict a hit. The suicidal mission was described by one writer as “equivalent to a stone thrown into a group of pigeons.” VT-6 followed Waldron’s lead but met a similar fate, without a single torpedo finding its mark. Most of their Mark 13 aircraft torpedoes traveled beneath the targets, and their detonators failed to explode or simply fell apart in the water. (It would take U.S. Navy experts several months to correct the defects in the Mark 13, during which time scores of airmen would lose their lives in vain.)

Ensign George H. Gay Jr., 25, the only survivor of VT-8, watched from his own ditched bomber as Waldron stood heroically in the cockpit of his downed plane, the water closing in. For the next few hours, hiding under his seat cushion, Gay had a unique view from the front stalls of the battle.

Three other downed American airmen were not so lucky. They were hauled aboard Nagumo’s ships, brutally interrogated, then dumped overboard, the legs of two of the three attached to five-gallon canisters. One of them evidently gave up the U.S. order of battle. Nagumo now realized he might be facing three enemy carriers, not two. This led to his second fatal decision, as he ordered the frantic, exhausted deck crews to switch the planes’ ordnance back to torpedoes. Once removed, the fragmentation bombs were left casually on the decks, along with exposed fuel lines. Nagumo also reversed course out of the wind, which delayed the launch of any more of his planes.

Of the 29 American planes in VT-8 and VT-6, only four, all from VT-6, made it back. A final disaster occurred when a wounded Wildcat pilot accidentally triggered his guns on landing, raking the island structure of the Yorktown and killing several men—including Lieutenant Royal Ingersoll, the son and namesake of the commander in chief in the Atlantic.

AT THIS POINT, the battle might well have looked lost to the Americans. But events were moving fast. Just after 10 a.m., the Enterprise’s oldest pilot, 39-year-old Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky, and his squadron of Dauntless dive-bombers were in the air hunting enemy carriers. They had been flying most of the morning and were running dangerously low on fuel. Then, at 9:55, McClusky spotted the broad, white, V-shaped wake of the Japanese destroyer Arashi. Just a few minutes earlier the destroyer had been hot on the heels of the American sub Nautilus, which had sneaked into Nagumo’s fleet. Having chased the Nautilus away with a dogged depth-charge assault, the Arashi was now returning at full speed to the main strike force, and McClusky followed.

It was then within the span of little more than 10 minutes that the tide of the battle—indeed, of the whole war—turned. McClusky had seen an opportunity in the Arashi’s wake and had followed it directly to three enemy carriers, the Kaga, the Akagi, and the Soryu, which were clustered vulnerably together. From somewhere above 15,000 feet, throwing his bomber into a steep 45-degree dive, McClusky targeted the 38,000-ton Kaga. He narrowly escaped colliding with Lieutenant Richard H. Best, who was diving on the same target but had pulled up.

McClusky and his flight went in unchallenged, the defending Zeros having earlier moved to low altitude to finish off the ill-fated torpedo planes. The sacrifice of Waldron and his men now paid off. McClusky’s planes hit the Kaga with a 1,000-pound bomb and at least three 500-pound bombs. “I’d never seen such superb dive-bombing,” noted one fighter pilot who escorted the bombers. “It looked to me like almost every bomb hit.”

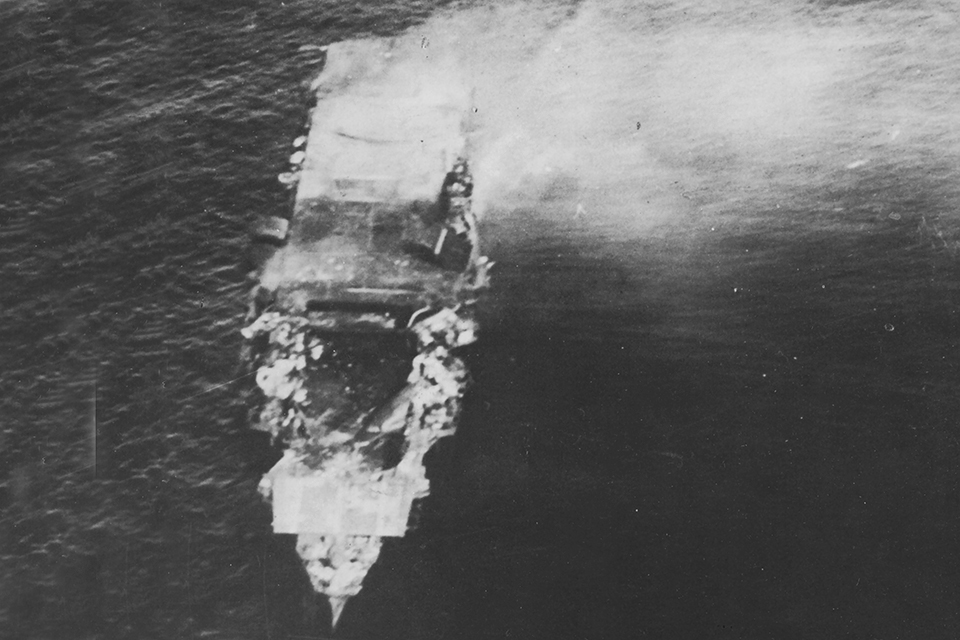

The 500-pound bombs did considerable damage to the Kaga’s berthing compartments, the upper hangar, and the bridge, where the captain and most of the ship’s senior officers were killed. But McClusky’s 1,000-pound bomb was the deathblow. It hit the Kaga amidships, penetrated the flight deck, and exploded on the upper hangar. It ruptured the ship’s systems of tanks and hoses that carry gas to the planes—the very lines that had been left strewn about following the change of plane ordnance from torpedoes to bombs. The bomb also made it impossible for the crew to fight the resulting fires: It damaged both the port and starboard fire mains and the emergency generator that powered the fire pumps and knocked out the carbon-dioxide fire-suppression system.

Fed by the high-octane fuel pouring out, fires detonated 80,000 pounds of bombs and torpedoes left unsecured on the hangar deck. A series of catastrophic explosions blew out the hangar sides and spread with terrifying speed through the ship.

Minutes later, Best and his two wingmen attacked the 35,000-ton Akagi, Nagumo’s flagship. The first bomb missed. Though the second bomb landed in the water, the shockwave jammed the Akagi’s rudder. The last bomb, dropped by Best, pierced the flight deck and exploded in the upper hangar among 18 bombers, dooming the Akagi.

At nearly the same time, dive-bombers from the Yorktown’s VB-3, led by Lieutenant Commander Max Leslie, hit and fatally damaged the Soryu. With that, three of the four carriers in Nagumo’s vaunted strike force were crippled. Scenes on the ships beggar description. The Kaga immediately lost 269 mechanics on its hangar deck, while 419 of the Soryu’s were similarly immolated. Fires raged on the lower decks, trapping engine room crews.

The destruction revealed critical faults in Japanese carrier design. Their flight decks were wooden, not armor clad as they were on Royal Navy carriers. Although American carriers had wooden decks, they also featured excellent fire-control systems and flash-proof doors. Compared to them the Japanese carriers were gimcrack affairs, highly flammable with poor firefighting capacity. Like the Zero fighter with its great speed and thin armor, the Japanese carriers reflected the Bushido-oriented national philosophy; everything was designed for a swift, aggressive war, with few measures for defense—or the protection of crews.

Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, the national hero who had led the attack on Pearl Harbor, was aboard the Akagi, which was now afire and dead in the water, its propeller drive destroyed. Confined to hospital quarters by a sudden appendix attack and operation, he broke out and staggered to the flight deck just as Best’s bomb struck. Narrowly escaping the blast, he ran into Captain Minoru Genda, the other architect of Pearl Harbor, who uttered laconically: “Shimatta!” (We goofed!) Fuchida escaped, the last man down a rope ladder to a lifeboat, though he broke both legs.

The Kaga and the Soryu both sank later that evening. The Akagi, the queen of flattops, the very symbol of Japanese air power, was scuttled before dawn the following day, June 5.

The fourth of Nagumo’s carriers, the Hiryu, had been spotted some 160 miles away the previous afternoon. At 3:50 p.m., Spruance, commanding TF 16, ordered the Enterprise to launch its final strike of dive-bombers, linking up with planes from the Yorktown. Only 24 took off—all that could still fly. Despite an assault by more than a dozen Zeros, the attack landed four, possibly five bombs on the Hiryu, setting the carrier ablaze. Its forward elevator was flung up against the bridge, rendering the ship unable to launch or receive its aircraft.

The Hiryu stayed afloat throughout the night of June 4. Before it finally sank, the emperor’s portrait was reverently removed from the ship in an elaborate ceremony featuring shouts of “Banzai!” Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi—flag officer of 2nd Carrier Division (Hiryu, Soryu) and possibly the Imperial Navy’s most competent and best-loved carrier commander—insisted on staying aboard; Japanese legend has it that he and the ship’s captain went down while calmly admiring the moon.

THANKS TO YAMAMOTO’S ORDER for radio silence, along with the Japanese “victory disease,” the Japanese supreme commander knew nothing of the disaster befalling his fleets until the very last minutes of the battle. At 7:15 p.m. on June 4, well after the last of his four carriers had been put out of action, Yamamoto sent a signal from the Yamato that shows he was hopelessly out of touch: “The enemy fleet, which has practically been destroyed, is retiring to the east. Combined Fleet units in the vicinity are preparing to pursue the remnants and at the same time to occupy AF.” (That is, the Midway atoll.)

Yamamoto was apparently still fantasizing about a Tsushima-style naval Armageddon. Even after he learned of his losses at sea and the destruction of all his carrier planes, he persisted in mounting a half-hearted attack on Midway, sending in heavy cruisers to shell the island. Two of those ships collided in the dark and were seriously damaged; one of them, the Mikuma, was later finished off by U.S. Dauntless dive-bombers. At last, at 2:55 a.m. on June 5, Yamamoto ordered the remains of his immense fleet to head for home.

The Battle of Midway was in effect over. American losses in their crushing victory totaled 144 aircraft and 362 dead—a heavy toll, but nothing like what had been expected. The Yorktown, already bloodied from the Coral Sea encounter, was also lost, though only after a courageous fight late in the battle. At 2:30 p.m. on June 4 the carrier had withstood the furious attack of dive-bombers dispatched from the Hiryu. Operating with efficiency not seen on the Japanese carriers, the Yorktown’s damage-control teams extinguished the fires and got the ship back in action in less than two hours. A short time later, however, a strike of the Hiryu’s torpedo planes (the last gasp from that doomed ship) hit with deadly effect. Two torpedoes ripped a huge hole in the Yorktown’s port side. Almost stationary, the ship listed to an alarming 26 degrees. Still, the ship stayed afloat until June 6, when—even as the American destroyer Hammann attempted its salvage—Japanese submarine I-168 fired a spread that put two more torpedoes into the Yorktown. A third torpedo blew the Hammann in half. At 3:55 p.m., Yorktown’s captain reluctantly gave the order to abandon ship, and at dawn on June 7, the brave ship finally went down.

AFTER THE BATTLE, Japan’s leaders presented Midway to their people as a great triumph. navy scores another epochal victory, read one headline. Even in the worst days of late 1944, Japan’s military leaders never admitted a single defeat. But more than 3,000 Japanese sailors and airmen died at Midway. The country’s four most powerful carriers were sunk, along with the heavy cruiser Mikuma. Nearly 250 planes were destroyed, the loss of their pilots representing a year’s graduating class. But all of that was hidden from the public.

In fact, after the brave Japanese veterans of Midway, many wounded or suffering appalling burns, were repatriated to Japan, they were promptly transferred, amid total secrecy, to a hospital ship under cover of darkness. They were then kept segregated from the rest of the country—forbidden to receive mail, telephone calls, or even visits from wives, “just like we are in an internment camp,” said an indignant Mitsuo Fuchida.

On recovering, most of the men were shipped off to the Solomons, many never to return or see their loved ones again.

His fleet sunk around him, Nagumo offered to take the traditional way out. But Yamamoto refused him, declaring, “If anyone is to commit hara-kiri because of Midway, it is I.” The next year, Yamamoto was killed when American planes ambushed his transport plane flying over Bougainville in the Solomon Islands. Nagumo eventually returned to combat duty but suffered several key defeats. In the waning moments of the 1944 Battle of Saipan, he killed himself, dying miserably in a cave after a shot to the head.

The loss of three of Japan’s best aircraft carriers in 10 minutes at Midway permanently ruined what had been its most successful naval weapons system of the war. Japan’s relatively backward industrial base could never catch up to U.S. production. More critically, it would never recover from the loss of so many planes and trained pilots. Whereas by late 1943 there would emerge an entirely new U.S. Navy, the losses of men and machines in 1941–1942 more than made good.

Following Midway, Nimitz would enjoy operational superiority for the first time in the war. There would be the occasional setbacks and reverses, and the fight would drag on for three and a half bitter and costly years.

But the United States would never again lose in the Pacific; in a way, Midway was the same kind of turning point for the Americans that the 1942 Battle of El Alamein in North Africa was for the British. It was a historic episode that combined skill, immense courage, technological superiority (in the capacity of punishment for U.S. carriers), and—with Lieutenant Commander Wade McClusky’s spotting the wake of the destroyer Arashi—extraordinary good luck.

Alistair Horne, a longtime contributing editor, has written more than 20 works of history, including The Terrible Year: The Paris Commune, 1871 and A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962.

[hr]

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2002 issue (Vol. 24, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Ten Minutes at Midway

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!