For nearly four years, Baroness Riedesel, wife of a German general, was shuttled around the colonies as part of the convention army—British and German soldiers captured at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777. The tale of her odyssey reveals a code of conduct that allowed.

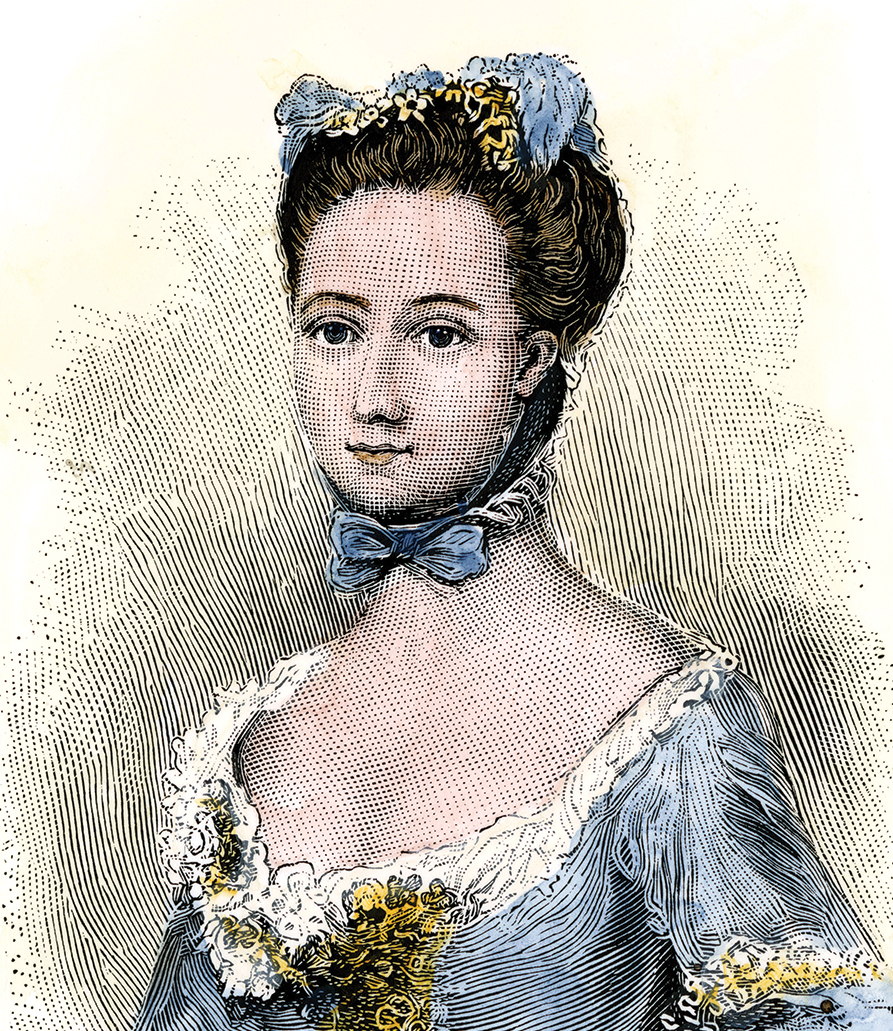

In May 1776, a German woman, her three small daughters and a servant set out from their estate in Germany on a journey to British Canada, via England. The woman, Friederike Charlotte Luise Riedesel Freifrau zu Eisenbach, embarked on what she called a “tour of duty”: She was off to join her husband, Major General Friedrich Adolph Riedesel Freiherr zu Eisenbach, a baron and commander of the German troops hired out by the Duke of Brunswick to help the British in their efforts to crush the American Revolution. Madame, as she was called by her contemporaries, could hardly have anticipated what was about to happen.

In October 1777, she witnessed the battle at Saratoga and the subsequent surrender of the British and German troops under Maj. Gen. John Burgoyne. She spent most of the duration of the Revolution as a prisoner of war, moving with the captured army, known as the Convention Army, from New York to Massachusetts, then through Pennsylvania to Virginia and finally back to New York and then Canada. In the 1790s, after her return to Europe, she wrote a detailed description of those experiences for her family and friends. Her publisher soon persuaded her to issue the personal and highly unusual account of the American Revolution as a book. The first of several editions of Die Berufs-Reise nach Amerika appeared in 1801 in Berlin. The title nicely captures the idea that Madame considered it her duty as a wife to follow her husband: It translates as Tour of Duty to America.

Madame’s experiences were by no means typical of the average prisoner of war. As a general’s wife and aristocrat, she had access to many prominent individuals. As a woman with small children, moreover, she probably experienced an unusually large share of kind gestures. Still, her descriptions of her many encounters with prominent British officers as well as Americans reveal that the state of war did not affect the ability to forge personal friendships. At all times, including immediately following a battle, individuals of high social status on all sides were expected to treat each other with the utmost respect and courtesy.

In December 1775 General Riedesel, a German career soldier with experience in the British service, received orders to command approximately 4,500 troops from Brunswick, a relatively small German duchy. They were to fight alongside British regulars in North America. He immediately put his business affairs in order, sold a farm that was difficult to manage and wrote his testament. His wife, Baroness Riedesel, would have set out with her husband had she not been pregnant at the time. The general, therefore, left his family in February 1776, heavy-hearted but with hope that they would join him as soon as possible.

It is likely that Madame knew little of North America and the Revolution when she decided to follow her husband across the Atlantic. Friends warned her that savages would devour her and her children, and that a significant portion of an American’s diet consisted of horses and cats. Madame’s mind, however, was made up. Even the most frightening stories could not persuade her to abandon her duty as a wife. On May 14, 1776, she, in the company of her three daughters, the older ones aged 4 and 2, and the youngest barely 10 weeks old, left the comfort and safety of her home. Rockel, her husband’s old and trusted manservant, insisted on traveling with her. She faced the journey with resolution and courage, lamenting only her ignorance of English.

Madame anticipated a brief stay in London and Portsmouth. However, she missed one vessel destined for America and was soon warned that it was becoming too dangerous to embark on the voyage so late in the year. As a result, she remained in England for about 12 months, until June 1777. While this unexpected delay postponed the reunification with her husband, she took advantage of the opportunity to study British customs and manners. By the time they left for North America, Madame and her two oldest daughters were not only dressed in British fashion but, more important, were also able to carry on basic conversations in English.

The family’s happy reunification took place on June 15, 1777, when the Riedesels finally met near Montreal. During the next few weeks, Madame and the children followed the army southward, toward Saratoga, N.Y. Madame’s recollections of the weeks prior to the Battle of Saratoga present a moving scene of almost idyllic family life. She noted: “We were very happy during these three weeks! The country there was lovely, and we were in the midst of the camps of the English and German troops.” To be sure, quarters tended to be cramped, and supplies were frequently inadequate. Indeed, Madame remembered, “Sometimes we had nothing at all.” Nevertheless, she wrote: “I was very happy and satisfied, for I was with my children and was beloved by all about me. If I remember correctly, there were four or five aides with us. The evenings were spent at cards, while I busied myself putting the children to bed.” It would have been difficult to notice that a war was raging in the land had not her husband been forced to leave for short periods of time to see to the troops under his command and to fight in several battles. She wrote later that, after the troops had crossed the Hudson River on September 13, the men and women “had high hopes for victory and of reaching the ‘promised land.’” Encouraged by Burgoyne’s optimistic pronouncement that “Britons never retreat,” they “were all in very high spirits” when they reached the plains of Saratoga on September 14.

On October 7, Burgoyne’s army encountered the American forces under Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates. Greatly outnumbered by an estimated 15,000 Americans, almost three times their number, the British and Germans were soon forced into retreat to Saratoga. Burgoyne spent one night at the country estate of Patriot Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, former commander of the Northern Department, before setting it on fire to prevent Americans from seeking cover there. By October 13, however, Burgoyne and his army were trapped by the overwhelming American force. Three days later, with hopes for a rescue by British reinforcements under Maj. Gen. Sir Henry Clinton all but vanished, Burgoyne surrendered.

Of the 5,756 troops that surrendered, 2,454 were British, 2,198 were German and 1,100 were Canadian. Of those, 383 British, 422 Germans and 67 Canadians were officers. Burgoyne was able to negotiate unusually generous terms of surrender because Gates was in a hurry to get the agreement signed. Although Burgoyne did not know it, Gates had intercepted a message suggesting that Clinton’s British army was indeed on its way. The treaty of surrender became known as the “Terms of the Convention,” and the captured British and German forces as the “Convention Army.” Burgoyne had insisted that the term “prisoner of war” not appear in the treaty. Similarly, in order to preserve as much honor as possible under the circumstances, the words “defeat,” “surrender” and “capitulation” did not appear anywhere in the document.

The defeated army, furthermore, was permitted to march out of camp with full honors of war, and the officers were permitted to retain their full baggage, including their side arms. Burgoyne had also demanded that all troops, whether German or British, receive equal treatment. This clause assured Burgoyne that the German troops would be regarded in every respect as British subjects and not as subjects of a neutral nation and as such, perhaps, enticed to desert. Finally, while women were not directly mentioned in the treaty, it also stipulated that all “Followers of the Army” would be part of the Convention Army and thus receive the same treatment as the soldiers. The Canadians were immediately escorted to the nearest British fort in Canada, where they were paroled with the stipulation that they not return to service in the war. The British and German soldiers, however, initially were ordered to march to Cambridge, Mass. During the course of the war, they gradually moved south, to Virginia, in order to distribute the burden of their upkeep among several states and to avoid their liberation by the enemy.

After the surrender and before their departure, high-ranking British and German officers were invited to visit Gates’ headquarters. At that time, Madame was unsure of what to expect, especially because she could not be certain that the Americans were familiar with the honorable customs of war. She wrote, “I confess that I was afraid to go to the enemy, as it was an entirely new experience for me.” So it was with mixed feelings that she and her three small daughters set out to rejoin her husband in the American camp. She remembered with gratitude that she “got into [her] beloved calash again, and while driving through the American camp I was comforted to notice that nobody glanced at us insultingly, that they all bowed to me, and some of them even looked with pity to see a woman with small children there.” Moreover, she was thoroughly relieved when, outside Gates’ camp, an American general approached her carriage, lifted the children out, “hugged and kissed them and then, with tears in his eyes,” helped her out. The man was General Schuyler.

While her husband and the other generals dined with Gates, Schuyler invited her to share supper with him. Madame claimed in her book that the meal of “delicious smoked tongue, beefsteaks, potatoes, and good bread and butter” was the best dinner she had ever enjoyed. “No dinner had ever tasted better to me,” she wrote. She seemed to realize the meal was especially enjoyable because, as she wrote, “I was calmer, I saw that everybody around me was calm as well; and most importantly to me, my husband was out of danger.” Schuyler also invited Madame to stay at his house near Albany, N.Y., where Burgoyne was lodging as well. To Madame’s surprise, Schuyler’s wife and daughters welcomed her and the children “not as enemies but in the friendliest fashion,” as she penned in her memoir. Even Burgoyne, who only days earlier had ordered the destruction of Schuyler’s favorite country estate, was treated with the utmost respect and sympathy. In fact, perhaps ashamed of his deeds and humbled by the Schuylers’ hospitality, Burgoyne apologized for the damage he had inflicted on the American’s property. The American general brushed his comment aside by insisting: “Such is the fate of war. Let us not talk about it any more.” Madame was deeply impressed with the Schuylers, whose “behavior was that of people who can turn from their own loss to the misfortunes of others.”

Madame’s amiable experience with the Schuylers was only one of several exceedingly pleasant encounters with prominent enemy families during her captivity. Though she expected a certain degree of respect from fellow captives, more than once she was overwhelmed by the amount of hospitality extended by Americans to her and her family during the course of the next few years. She, in turn, was respectful to all individuals, whether Patriot or Loyalist. In fact, what mattered most to her were the individual’s behavior and manners; she did not hesitate to invite a staunch Patriot to her table, or to a ball, if he conducted himself respectably.

In November 1777, the Convention Army was sent to Cambridge. The Riedesels and other officers were comfortably lodged in abandoned Loyalist homes on Tory Row (now Brattle Street). The lower ranks, on the other hand, were forced to spend the year in poorly constructed barracks on Winter Hill. It is remarkable, as one historian has noted, that only 220 Germans deserted during this time, apparently tempted by widely distributed fliers that promised a prosperous future in America to any German who left the army for good. Madame, however, did not consider this time to be one of hardship; indeed, she wrote later that this was a “happy and joyous” year for her family, who lived in “one of the most beautiful houses.” While the men were prohibited from traveling into Boston, she was not and paid several visits to Schuyler’s eldest daughter, Angelica Carter, who resided there. The Carters, in turn, joined the Riedesels for dinner in Cambridge on numerous occasions, including a ball and supper Madame gave in honor of her husband’s birthday.

In the fall of 1778, the Convention Army received orders to move to Virginia. While passing through Connecticut, the Riedesels had a chance encounter with the Marquis de Lafayette, the 20-year-old French aristocrat whose enthusiastic embrace of republican values and offer to serve in the Continental Army without pay had been accepted by Congress in the summer of 1777. The family immediately invited him to join them for dinner despite their limited provisions. Madame knew that the marquis appreciated good food, and she was proud of her ability to cobble together a respectable meal. The marquis, she later wrote, “was so polite and pleasant that we all liked him very much.” Madame, whose command of English remained limited throughout her stay in the United States, was especially happy to be able to converse in French with him. Indeed, she noted with glee that he “had a number of Americans in his party, who almost jumped out of their skins because we always talked French.” She speculated that they may have been “afraid that, being on such friendly terms with him, we might win him over to our side, or that he might tell us things which they did not want us to know.”

Madame and the marquis shared a similar social position and cultural understanding. Both were members of the aristocracy, both spoke French, the language of the upper classes, and both understood the honorable customs of war. In fact, it was much easier for Madame to converse with this young Frenchman than it was to speak with a common soldier in the Brunswick regiment. The average soldier enlisted in the regiments was of humble background, uneducated and worlds apart from a woman like Madame. Many were not even from Brunswick, but had been pressed into service by ruthless agents scouring the countryside for young men passing through the duchy. Although Madame had plenty of sympathy for the miserable plight of the common soldiers who fought on her side during the war years, she could relate much better to enemy officers.

After traveling through Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Maryland, the Convention Army reached Charlottesville, Va., in January 1779. The troops found unfinished barracks, many with several inches of snow covering the bare floors, which the men were ordered to finish themselves. The officers and their families, including Madame, were instructed to secure lodgings in the surrounding neighborhood. British Maj. Gen. William Phillips, Burgoyne’s commander of artillery and one of the Riedesels’ closest friends during those years, was able to find a home at Blenheim, the stately residence of the prominent planter Edward Carter. The Riedesels rented Colle, the house owned by Philip Mazzei, Thomas Jefferson’s neighbor and friend, who was about to depart for Europe in an effort to secure funding for the United States. Madame’s opinion of Mazzei was exceedingly low, for he failed to treat her family with the customary respect. She recalled later that “on the first day, when he had a ram killed, he gave us only the head, the neck, and the giblets, even though I pointed out to him that it would have to do for more than twenty people.” Needless to say, she eagerly awaited the day of Mazzei’s departure, particularly because the house proved to be too small to accommodate the party comfortably. In fact, Riedesel soon hired artisans to build them a simple but more spacious home in Charlottesville.

Generally, Madame had a low opinion of Virginians. They “are mostly indolent,” she noted, and that from what she had been told, “the morals of the people in this part of the country does not make a favorable picture.” Indeed, she reported having heard of several scandalous incidents, including that of a Virginian who had exchanged wives with his own son. The poor treatment of slaves earned Virginians additional criticism; however, her view of the institution of slavery was ambivalent. She commented that many “plantation-owners in Virginia have numerous Negro slaves and do not treat them well,” and that they “let the slaves walk around stark naked until they are between fifteen and sixteen years old, and the clothes which they give them afterwards are not worth wearing.” She also admitted, however, that “there are, of course, good masters too.” Their slaves were well-dressed and “very good servants, and very faithful to their masters.” Madame never mentioned that some of the prominent Virginia and Maryland families with whom she forged enduring friendships owned slaves.

While there is no record that the Riedesels ever met George and Martha Washington during their stay in Virginia, they did meet Thomas Jefferson and his wife, Martha, and the family of Charles Carroll of Carrolltown, a prominent Maryland planter, lawyer and signer of the Declaration of Independence who served in his state’s and national governments for 27 years. They became close friends of the Carroll family, making their acquaintance when the Carrolls and the Riedesels visited Frederick’s Springs, Va., in the summer of 1779. General Riedesel had received special permission from Thomas Jefferson to visit the springs in hopes of speeding his recovery from sunstroke he had suffered while working in the garden at Colle. The Carrolls were there to improve the physical and mental well-being of Mrs. Carroll. The lingering effects of a near-fatal illness, combined with the death of one of her children in the fall of 1778 and the difficult birth of another that year, had led her to an increasing dependence on laudanum. By the spring of 1779 she was getting the addiction under control, and the family decided to travel to the bath to reinforce this success.

While Charles Carroll found the six-week vacation dull—he hated “this idle sauntering life” of “Dancing & tea-drinking” for the ladies and gaming for the gentlemen—his wife benefited thoroughly from the water, the air and, most of all, from the social life. Carroll’s impression of the German general and Madame was extremely favorable. He wrote to his father that “the General is polite[,] well bred, & apparently a good natured man: his lady is like wise [sic] well bred & sensible.” In another letter, only a few days later, he again emphasized that “Madame Reidesel [sic] is really an amiable & well bred lady—the general is also much of the gentleman affable & good natured.” Madame did not think very highly of Carroll, whom she described as “not very loveable, but rather terse and stingy.” The two women, however, became very close, spending much of their time with a German officer in Riedesel’s entourage, Captain Friedrich Wilhelm von Geismar, who played the violin while Madame sang Italian arias and Mrs. Carroll listened. Madame’s characterization of Mrs. Carroll demonstrates that political affiliation was secondary to character. She wrote in her memoirs that “Madame Garel,” as she called her in her journal, was a “fervent American Patriot, but reasonable and we became close friends.”

Madame subsequently accepted an invitation to visit the Carroll estate, Doughoregan Manor, near Baltimore. That she was apparently unaware of her host family’s prominence is suggested by her candid description of Charles Carroll’s father, Charles Carroll of Annapolis. She did not mention his name but instead described him as “an old father-in-law, eighty-four years of age, of good health, sprightly humor and most extreme neatness.” Nor did Madame seem to know that her hosts belonged to one of the wealthiest families in North America at the time. Indeed, she commented that dinner was served on silver, “but without splendor.” The estate, however, struck her as particularly beautiful; in fact, she described the view from the family’s vineyard as the most spectacular she had ever enjoyed in America. Before her departure after about 10 days, Riedesel’s aide-de-camp, Captain John Freeman, built a “temple, adorned with flowers and dedicated to friendship and gratitude.” Before her death in 1782 at age 33, Mrs. Carroll had written to Madame that she was regularly decorating this token of affection with fresh flowers.

One of the most enduring friendships that the Riedesels forged during their stay in Virginia was with Thomas Jefferson and his family. As one of Virginia’s leading social and political figures, Jefferson was concerned about the well-being of the Convention Army while they were camped in his state, and he did what he could to improve the lot of the troops. Jefferson’s remarks to British General Phillips epitomized the congeniality with which enemy officers were to treat each other. The future president of the United States stressed that “the great cause which divides our countries is not to be decided by individual animosities.” In fact, he continued, “To contribute to neighborly intercourse and attentions to make others happy is the shortest and surest way to being happy ourselves.” Interestingly, Madame never mentioned the Jeffersons in her memoirs, possibly because in 1779 Thomas Jefferson was not as prominent as he would become later. Nevertheless, the two families’ correspondence demonstrates that the Riedesels, along with several other German officers, spent many happy hours at Jefferson’s home, Monticello. In fact, when news of their impending exchange reached Virginia in the summer of 1779, both families were saddened. In a letter to General Phillips dated June 25, Jefferson expressed his regrets of losing his “neighbors, in which character I with pleasure considered yourself, General and Madme. de Riedesel for that cause as much as any other is not likely to add to my happiness.” Two weeks later, on July 4, Jefferson responded to Riedesel’s congratulations to Jefferson’s recent election as Virginia’s governor. “I thank you for your kind congratulations,” Jefferson wrote, “tho’ condolances [sic] would be better suited to the occasion…on account of the…agreeable society I have left, of which Madme. Riedesel and yourself were an important part.”

In December 1779, General Riedesel expressed his gratitude and esteem for Jefferson when he wrote that “you will be assured that I shall ever retain a grateful rememberance [sic] of [your assistance and hospitality] and deem myself singularly happy, after this unnatural war has ended, to render you any Service in my power as a token of my personal regard for you and your Family.” Jefferson, in response to several similarly gushing expressions of gratitude, responded that his gestures “never deserved a mention or thought.” In fact, he was ashamed that the “peculiar situation in which we were put it out of our power to render your stay here more comfortable.” The correspondence between the two families continued well after the Riedesels had returned to Europe.

Upon receipt of the news of their exchange that summer of 1779, General Riedesel left Virginia almost immediately and Madame followed separately in August to reunite with him in Yorktown, Pa. It was on this trip that Madame visited the Carrolls in Maryland. During their long odyssey to final release, the family met several prominent British officers, all of whom treated them with the utmost respect and hospitality. Major General Lord Charles Cornwallis, commander of British forces in the southern theater, and General Sir Henry Clinton, for example, paid visits when the family was lodging at the recently vacated house of New York’s governor, William Tryon, who had left for England.

Madame’s account of the emerging friendship with Clinton reveals the degree of decorum that was involved in such relationships. “As with all Englishmen, it was difficult at first to get to know him,” she recalled. “His first visit was to us merely a matter of form, paid to us in his capacity as commander in chief, attended by his whole staff.” Madame soon confided in their mutual friend, General Phillips, that the family had enjoyed Clinton’s company and was hoping for less formal encounters. In response, Clinton extended a gesture of friendship by offering the use of his country home for the summer of 1780. He further demonstrated the increasingly less formal and more personal nature of their friendship when he visited the family several times, now clad in hunting attire and accompanied by only one adjutant. He told Madame that he knew “she preferred to see [him] as a friend, and since [he] felt the same, she should always regard [him] as such.” Indeed, Madame understood Clinton’s subsequent promotion of her husband to lieutenant general, his allocation of British pay and the command of the British troops on Long Island as manifestations of Clinton’s personal affection for her family.

Clinton also introduced the Riedesels to a man who would become one of the most infamous individuals of the Revolution, Major John André. American Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold, famous for his contribution to several American accomplishments, including the victory at Saratoga, had secretly negotiated the surrender of West Point with André. In fact, André embarked on his journey to report the agreement to his superiors the day after his encounter with Madame, only to be captured by the Americans and hanged as a spy. Madame had pity for André. “It was very sad,” she wrote, “that this excellent young man had become a victim of ambition and a good heart which had compelled him to undertake such a deplorable mission” in place of an older and more experienced officer.

For two years after leaving Virginia, they were shuttled about in New York state and Pennsylvania due to congressional confusion and changes in opinion. Finally, in July 1781, the Riedesels were allowed to leave for Canada. Two years later, in August 1783, Madame’s journey through North America came to an end when the family departed for Europe. It was perhaps a blessing that they spent almost the entire duration of the Revolutionary War in captivity. After all, they were removed from the immediate dangers of warfare and, at the same time, permitted to enjoy the company of some of the most prominent American and British officers of their time. Perhaps it stands as a symbol of this experience that Madame returned to her home in Germany with another child, born in the newly established United States and aptly named Amerika.

Originally published in the August 2006 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.