July 30, 1955, marked the 10th anniversary of the worst disaster in American naval history—the sinking of USS Indianapolis. That Saturday retired salesman and World War II Navy veteran Clair Young was at home in southern California reading a day-old Los Angeles Times article that related how men in the heavy cruiser’s Radio Room 2 knew an SOS message had gone out following the vessel’s torpedoing by a Japanese submarine, but they believed no one had received it. A week later, on Aug. 6, 1955, a piece in the Saturday Evening Post stated unequivocally no SOS had been received.

Young knew better. On that fateful night a decade earlier he’d been a young radioman assigned to the sprawling U.S. Navy facilities at Tacloban, on the Philippine island of Leyte. He had personally delivered a copy of the cruiser’s SOS message to his commanding officer. What happened in the hours, days and years that followed is a story of unimaginable fear, tragedy and betrayal—yet it is also one of redemption.

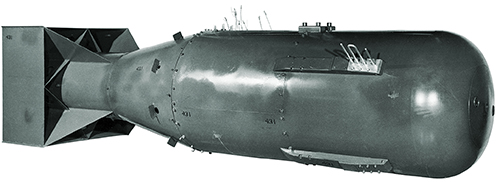

Launched in 1931, Indianapolis saw extensive combat in several World War II campaigns, including providing naval gunfire support for the landings on Tarawa, the Marshall Islands, Saipan, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Damaged by a Japanese bomb during the latter operation, the cruiser underwent repairs in California. On completion of the work Indianapolis was tasked with a secret mission of paramount importance. On July 26, 1945, the warship delivered key components of Little Boy, the atomic bomb that would be dropped on Hiroshima, to Tinian, in the Northern Mariana Islands. The nature of the materials was unknown to the cruiser’s crew and even to its commander, Capt. Charles B. McVay III. Its delivery mission completed, Indianapolis sailed to Guam and then got underway for the Philippines.

Shortly after midnight on July 30 two out of six Type 95 torpedoes fired by the Japanese submarine I-58 slammed into the cruiser’s starboard side. Fatally damaged, Indianapolis went down within 12 minutes. During that brief window McVay ordered Radio Room 1 to dispatch an SOS. His command could not be executed, however, because Radio 1 was damaged and none of its equipment worked. In Radio 2 Chief Warrant Officer Leonard Woods was busy pounding out a distress signal. He stayed as long as he could, urging the younger radiomen to grab life jackets and abandon ship. Woods went down with the ship.

Of the 1,195 men aboard Indianapolis fewer than 900 made it into the water. Many of those who did were suffering from third-degree burns, in excruciating pain and would not survive the night. Stories abound of sailors trying to help injured shipmates whose pain was magnified by the exposure of their broken bones and seared skin to salt water.

By the end of the first day the unimaginable occurred—the arrival of packs of sharks. At first survivors tried gathering in protective groups. The predators picked off any lone swimmers flailing in the water. Men in the vicinity of a victim would hear a bloodcurdling scream, then he was gone. The sharks—believed to be mainly oceanic whitetips—killed an estimated 50 crewmen a day.

After a few days in the water survivors started hallucinating. Some were convinced they could see islands in the distance and swam toward them, never to return. Others thought the ship was beneath them, full of food and water. They unbuckled their life jackets and sank to their deaths. Others couldn’t resist the temptation to drink seawater, believing they could filter out the salt through their fingers. They, too, soon succumbed.

Those Indianapolis crewmen who managed to survive the sharks, sunstroke, dehydration and delusions were saved by a simple twist of fate.

Flying over the vicinity of the wreck in a PV-1 Ventura patrol bomber on the morning of August 2, Navy Lt. j.g. Wilbur Gwinn happened to be in the underbelly of the plane, trying to tie down a loose antenna, when he spotted a miles-long oil slick in the ocean below. The crew had received no reports of any distressed American vessels in the area, so Gwinn and crew assumed the oil was from a stricken Japanese submarine and prepared to release a string of depth charges on the slick. As the Ventura began its run, however, crewmen noticed irregular bumps on the otherwise smooth surface of the ocean. Wanting a closer look, Gwinn took the aircraft down to 300 feet. Startled by the sight of groups of men clinging together down the length of the slick, he radioed an urgent request for rescue ships and planes.

At Peleliu Airfield in the Palau Islands Lt. Adrian Marks and his crew received orders to take their PBY-5A Catalina flying boat—call sign Playmate 2—to the coordinates provided by Gwinn. En route Marks flew over the destroyer escort USS Cecil J. Doyle and radioed its captain, Lt. Cmdr. W. Graham Claytor Jr., that his ship would probably be rerouted to the rescue scene. Claytor concurred and on his own initiative set a course for the area.

The PBY flew on. When it reached the scene—some 280 miles north of Peleliu—its crew was stunned to find hundreds of men in the water. Marks took Playmate 2 down, and as the flying boat passed over the survivors, the crew tossed out every bit of rescue gear the plane carried. Knowing the few rafts would not accommodate all the survivors, Marks disobeyed standing orders not to land in the open ocean. Carefully maneuvering through the oil-covered swells, the PBY picked up more than 50 men. With no room left in the seaplane’s interior, Marks ordered additional survivors bound to the PBY’s wings mummy-style in parachutes. Obviously unable to take off, the aircraft and the men aboard it could only wait for rescue ships.

It was just before midnight when the first vessel, the destroyer escort Doyle, arrived. Despite the very real risk of submarine attack, Claytor ordered the ship’s searchlights turned on to let the men in the water know help was at hand and make them easier to locate. As his crew brought aboard survivors, Claytor asked them their ship’s name and was shocked by the response. His cousin Louise was married to Indianapolis’ captain, McVay.

Doyle and six other ships ultimately pulled from the water 316 Indianapolis survivors out of the original crew of 1,195. Two rescued sailors later died.

Questions regarding the Indianapolis disaster—the U.S. Navy’s largest loss of life at sea from a single vessel—began almost before the rescue vessels reached shore. Why did the cruiser not have a destroyer escort? Why wasn’t McVay notified of Japanese submarine activity along his route? Why wasn’t Indianapolis listed as missing when it failed to arrive in the Philippines as scheduled?

For the time being such questions went unaddressed, largely because a Navy court of inquiry recommended the cruiser’s captain be court-martialed. It determined McVay had hazarded his ship by failing to take an evasive zigzag course, despite the fact his orders had left zigzagging to his discretion. Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, disagreed with the court’s recommendation and instead issued McVay a letter of reprimand and returned him to duty.

The controversy might have ended there were it not for Fleet Adm. Ernest King, commander in chief of the U.S. Fleet and chief of naval operations. Overturning Nimitz’s decision, King recommended McVay face court-martial on two counts—failure to zigzag and failure to issue a timely order to abandon ship. The postwar proceeding convened in Washington, D.C., in December 1945. The Navy sought to bolster its case by having I-58’s captain, Mochitsura Hashimoto, testify, though to the prosecutors’ surprise he stated that, given the submarine’s position in relation to Indianapolis, zigzagging would not have altered the cruiser’s fate. Regardless, the court-martial panel found McVay guilty of not having followed a zigzag course. He was not convicted of the other charge.

In view of McVay’s excellent wartime record before the sinking of Indianapolis, in February 1946 Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal remitted the guilty verdict in its entirety and ordered the captain restored to active duty. McVay remained in the Navy until 1949, when he retired as a rear admiral.

For years after the war McVay received hate mail from the relatives of some of the men who perished in the sinking

For years after the war McVay received hate mail from the relatives of some of the men who perished in the sinking. Those letters not intercepted by wife Louise he kept bound up by string as a reminder. On July 30, 1960, McVay was the guest of honor at the inaugural reunion of Indianapolis survivors, none of whom blamed their former captain for the ship’s loss. But the hate mail never stopped. On Nov. 6, 1968—after having lost Louise and a grandson to cancer—McVay walked onto the back porch of his Connecticut home in uniform and killed himself with his service pistol. He was 70 years old.

Clair Young’s lifelong quest to set the record straight regarding Indianapolis’ SOS began when he read those 1955 articles in the Los Angeles Times and Saturday Evening Post. Knowing what he had read was wholly inaccurate, he immediately wrote a letter to then Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Arleigh Burke explaining how he had received a distress message from Indianapolis at approximately 12:30 a.m. on July 30, 1945.

“I personally delivered this message to the senior officer present, Commodore Jacob H. Jacobson U.S.N.,” Young wrote. “The message, although garbled, identified the ship, its position and its condition. His answer in effect was: ‘No reply at this time. If any further messages are received, notify me immediately.’ I feel that it is my duty to let it be known that the ‘lost’ distress signal was received.”

The Navy’s Civil Relations Division responded with a letter thanking Young for his “contribution to the distressing history of the sinking of the USS Indianapolis” while carefully pointing out that published accounts by individual survivors did not represent the official position of the Navy.

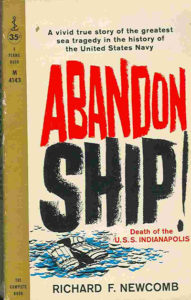

The Navy’s polite dismissal did not deter Young. When wartime naval correspondent Richard F. Newcomb’s classic account of Indianapolis’ loss, Abandon Ship! was published in 1958, Young contacted the author and told him of the cruiser’s SOS message. While the nature of their conversation is lost to history, Young’s home library contains an autographed copy of Abandon Ship!

The Navy’s polite dismissal did not deter Young. When wartime naval correspondent Richard F. Newcomb’s classic account of Indianapolis’ loss, Abandon Ship! was published in 1958, Young contacted the author and told him of the cruiser’s SOS message. While the nature of their conversation is lost to history, Young’s home library contains an autographed copy of Abandon Ship!

In 1990 Dan Kurzman’s Fatal Voyage took a comprehensive look at the Indianapolis story. After reading a San Francisco Chronicle article about the book, Young reached out to Kurzman. According to a Jan. 30, 1991, article in the Chronicle, Kurzman had several conversations with Young and concluded, “I believe that what Young says is true.” Kurzman rewrote a passage in the paperback edition of his book, adding he knew of three reports from radiomen who had received Indianapolis’ SOS. It marked the first published acknowledgment of anyone having received the cruiser’s SOS.

That same month Young received another request for information—this one from McVay’s son, Kimo. In his response Young detailed the events of that fateful night and his suspicion Commodore Jacobson had been drinking. The officer’s terse “No reply at this time,” Young felt, had been a missed opportunity to quickly rescue hundreds of Indianapolis survivors.

In the 1990s Young reached out to Capt. William J. Toti, then commander of the fast-attack submarine USS Indianapolis, to share the story of the SOS message. Toti checked out the story with the Naval Historical Center (present-day Naval History and Heritage Command), only to be told its researchers could verify neither Young’s account nor the two other reports that had surfaced regarding Indianapolis’ SOS. Toti offered to help Young, but by then the intrepid crusader was worn out. What Young perceived as the Navy’s unwillingness to correct the record had led to a decline in his health, and on Aug. 24, 1997, he passed away at age 75. His wife, Eleanore, continued his fight.

So did a sixth-grade history buff in Pensacola, Fla.

In 1997 Hunter Scott chose the sinking of Indianapolis as the subject of his project for National History Day. The 12-year-old ultimately sent a detailed questionnaire to more than 100 survivors, scores of whom either responded by mail, spoke with the boy on the phone or met him in person. The information and documents Scott gathered convinced him McVay should be exonerated. His effort drew national media attention. Scott appeared on television several times, and on Sept. 14, 1999, he and several members of the USS Indianapolis (CA-35) Survivors Organization testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee.

The Senate Armed Services Committee hearing ultimately prompted Congress to issue a joint resolution exonerating McVay for the loss of Indianapolis

When asked by Sen. Bob Smith of New Hampshire about reports he’d received regarding SOS messages from the cruiser, Scott replied he’d gotten three. Russell Hetz, who as a young sailor had been aboard the harbor examination vessel LCI-1004 in Leyte harbor, told Scott his ship had monitored two Indianapolis SOS messages, spaced about eight and a half minutes apart. But since Hetz and fellow crewmen didn’t believe a heavy cruiser could sink so quickly, they wrote off the distress calls as Japanese deception.

In the second report Don Allen, a sailor based on Tacloban, said that on the night of the sinking his commander had left orders not to be disturbed, so he took the initiative to send two seagoing tugs to check out the report. When his commanding officer returned from playing cards, Allen said, he ordered the tugs back to port.

The third report, the one that most interested Sen. Smith, was Clair Young’s. Eleanore Young had provided Scott with copies of her husband’s 1955 letter to the Navy, the department’s response and Clair’s 1991 letter to Kimo McVay. In Smith’s eyes the collection of correspondence and testimony of the witnesses were undeniable proof an SOS had been received but hadn’t been acted on. At the end of the hearing survivor Jack Miner—who had been in the cruiser’s radio room on its last night—came up to Scott with tears in his eyes. He was moved to finally know the SOS signal he had witnessed—and for which CWO Woods had so valiantly given his life—had been heard.

The hearing ultimately prompted Congress to issue a joint resolution exonerating McVay for the loss of Indianapolis. President Bill Clinton signed the nonbinding resolution on Oct. 30, 2000. Concerned the Navy might not actually place the signed exoneration in McVay’s official personnel file, the survivors requested that Toti, former captain of the decommissioned submarine USS Indianapolis, be allowed to do so in his new capacity in Naval Operations at the Pentagon. He did, finally ending a crusade for justice that had lasted nearly six decades. MH

California-based Marty Pay is an insurance broker and military history buff. In addition to the books mentioned in the story, for further reading he recommends In Harm’s Way, by Doug Stanton; Left for Dead, by Pete Nelson; and Indianapolis, by Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic. All three mention Clair Young’s story in the absence of corroborating witnesses or Navy records.