In October 1943 U.S. Lockheed P-38 Lightnings were briefly involved in an ambitious British operation in the Aegean Sea, providing cover for the Royal Navy, carrying out fighter sweeps and bombing enemy ground installations. Despite chalking up multiple victories during one of the most lopsided air actions of the war, no sooner had they made their presence felt, than the P-38s were withdrawn to continue operations over southern Europe.

By the fall of 1943, the war on the Eastern Front was not going well for Germany, the Afrika Korps had been defeated in Tunisia and the Allies had landed in Italy and were pushing north toward the Reich. Italian leader Benito Mussolini had been ousted in July, and in September Italy severed its alliance with Germany and declared an armistice. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill saw this as an opportune time to open a new front in the Aegean, ideally with the assistance of resident Italian forces. Such a move would increase pressure against the Wehrmacht and might even encourage Turkey to join the Allies. Already heavily engaged elsewhere, however, the U.S. had no interest in becoming involved in a sideshow in the eastern Mediterranean. Notwithstanding American opposition, British-led forces were deployed without delay to the Italian-occupied Dodecanese islands off Turkey’s southwestern coast.

Rhodes, with its all-important airfields, was key to a successful British strategy. An advance party parachuted onto the island to negotiate terms with the Italian commander, but it achieved no useful purpose. Very soon afterward Rhodes fell to the Germans. In addition to the airfields on Rhodes, the Luftwaffe also possessed air bases on Crete and mainland Greece. Undeterred, Britain established a significant presence elsewhere in the Dodecanese and also on Samos, farther north. Detachments from two Supermarine Spitfire squadrons were ordered to Kos, the only island in British hands with facilities for short-range fighters. Longer-ranging multiengine aircraft were based farther afield, in Cyprus, the Middle East and North Africa.

Adolf Hitler could hardly ignore a British presence in the eastern Mediterranean, as the German war effort was partly reliant on natural resources imported from the region. Greece, in particular, was a valuable source of ore, including chrome (used in armored steel production) and bauxite (from which aluminum was extracted). It was also important to protect the Romanian oilfields and refineries at Ploesti.

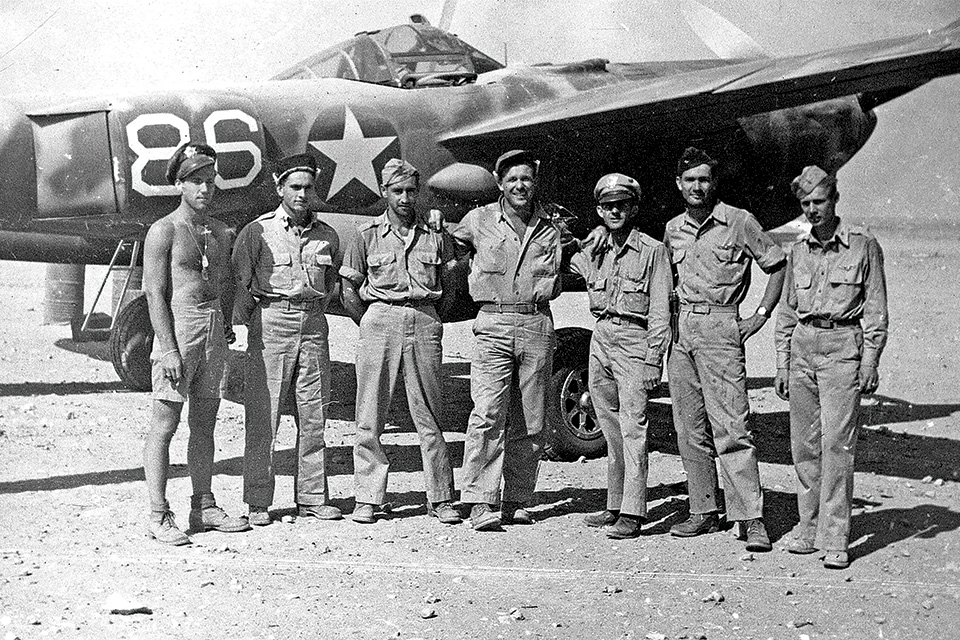

German forces took immediate action to counter the Allied threat, advancing on one island after another. Kos fell after a short battle on October 4. That same day, six squadrons of P-38 Lightnings of the U.S. 1st and 14th Fighter groups flew from Tunisia to Gambut in Libya to assist with continuing British efforts in the Aegean.

Leros, garrisoned by Co-belligerent Italian army and navy personnel and several thousand mainly British troops, would be the next major German objective. In an effort to prevent or at least delay the expected invasion, Allied submarines and warships struck at enemy shipping, achieving a major success on October 7 by sinking the troop transport Olympos along with accompanying vessels. The Germans responded with a Junkers Ju-87D Stuka attack that damaged the light cruisers HMS Penelope and Sirius. At least 20 were killed and up to 57 more injured.

Another Allied naval formation, Credential Force, was also in the Aegean at this time. It comprised the light cruiser HMS Carlisle and four destroyers: Petard, Panther and, initially, Aldenham and the Greek Themistocles. The latter pair were relieved by the destroyers HMS Rockwood and the Greek Miaoulis during the afternoon of Friday, October 8.

Late on Saturday morning, the five ships were retiring southeast between Rhodes and Karpathos. American P-38s and Royal Air Force Bristol Beaufighters had been covering the force, but toward midday several minutes elapsed during which there was no air cover. As fate would have it, Ju-87Ds of I Gruppe, Sturzkampfgeschwader (dive bomber wing) 3 (I/StG.3), operating from Megara on the Greek mainland, arrived overhead at this opportune time. One Stuka after another dived on their respective targets. Panther received a direct hit, split in two and quickly sank. Several bombs struck Carlisle aft, with at least one detonating on impact; other bombs burst only after passing completely through the ship. Carlisle remained afloat but was immobilized.

All but one Stuka returned to base (a Ju-87D-4 was reported missing after having been struck by anti-aircraft fire). The remaining I/StG.3 aircraft only just avoided contact with approaching P-38s of the 37th Fighter Squadron. Squadron commander Major William Leverette described in his combat report what happened next:

“On October 9, 1943, our Squadron took off at 1030 with nine planes to cover a Convoy of one Cruiser and four Destroyers. Two planes were forced to return to base because of engine trouble shortly after take off, leaving seven planes—a four ship Flight led by the undersigned and a three-ship Flight led by Lt. [Wayne] Blue. We sighted the convoy at 1200 hours, approximately fifteen miles East of Cape Valoca on Island of Scarpanto [aka Karpathos]. The convoy had been attacked and the Cruiser was smoking from the stern. During our first orbit around the Convoy, while flying a Southwesterly course at 8,000’, Lt. [Homer] Sprinkle called out ‘bogeys at one o’clock, slightly high, approaching the convoy from the Northwest.’ We immediately changed course to pass behind the bogeys and began a gradual climb. Shortly thereafter, we identified the bogeys as JU-87’s, in three flights, totalling approximately twenty-five.”

Unlike I Gruppe, II/StG.3 had arrived at the worst possible time. While some Stukas managed to attack the convoy, the American fighters quickly intercepted the slower dive bombers. Leverette’s report continued:

“Lt. Blue implicitly followed instructions to maintain his flight of three planes at altitude to cover my flight as we attacked the JU-87’s at about 1215. My flight immediately dived to the left and attacked the JU-87’s from the left quarter. I attacked an E/A [enemy aircraft] in the rear of the formation, fired at about 20° and observed smoke pouring from left side of engine. I broke away to the left and upward, attacking a second E/A from rear and slightly below. After a short burst at about 200 yards this E/A rolled over and spiralled steeply downward. After breaking away to the left again and turning back toward the formation of JU-87’s, I saw both E/A strike the water. Apparently neither rear gunner fired at me. I attacked another E/A from slight angle, left rear, firing just after rear gunner opened fire. He ceased firing immediately and pilot jumped out, although I did not see the chute open. I continued into the formation, attacked another E/A from 30°, observing cannon and machine gun hits in engine. Large pieces of cowling and parts flew off and engine immediately began smoking profusely as the E/A started down. Breaking away and upward to the left, I re-entered the formation and opened fire with cannon and machine guns on another E/A at approximately 15°. The canopy and parts flew off and a long flame immediately shot out from rear of engine and left wing root, rear gunner jumping clear of E/A. Continuing into formation and attacking another E/A from slight angle to left rear and below, I was forced to roll partially on my back to the left to bring my sight onto the E/A, opening fire at close range. I observed full hits in right upper side of engine which immediately began to smoke. I broke away slightly to the left, and my Element Leader, Lt. [Harry] Hanna, saw the enemy aircraft strike the water. Attacking another aircraft from behind and slightly below, the rear gunner ceased firing after I opened a short burst. The enemy aircraft nosed downward slightly and I closed to minimum range, setting the engine on fire with full burst into the bottom of fuselage. The enemy aircraft dive [sic] abruptly and I was unable to break away upward and in attempting to pass under right wing of the aircraft, three feet of my left propeller sliced through the enemy aircraft. We engaged the JU-87s until they passed over the South coast of Rhodes at approximately 1230 hours.”

Writing about the action 50 years later, Bill Leverette also revealed:

“On two of my passes through the Stukas I deliberately continued on after the leader of that bunch with every intention of getting him, too. But it turned out this guy had been shot at before! I was closing on him pretty fast. Just as I got within firing range he went into his act. Now, I knew about evasive action, of course, but had never really seen any. Well, I was about to get a demonstration by a master. I wouldn’t have believed any airplane could be made to jink and jerk in so many directions and attitudes, so quickly, so unpredictably. He flew it every way but right!

“There was no getting the gun sight on him. Nobody could have ‘followed’ him in any airplane, to say nothing of a P-38.

“I gave him a couple of squirts of the 50s as I closed on him, more in amazement, I suppose, than with any real expectation of hitting him. Same thing on the second pass, except he started sooner, and I may have given him only one squirt. All told I probably wasted no more than 3 to 4 seconds of fire on him. Enough to knock down a Stuka, though, when you hit it.”

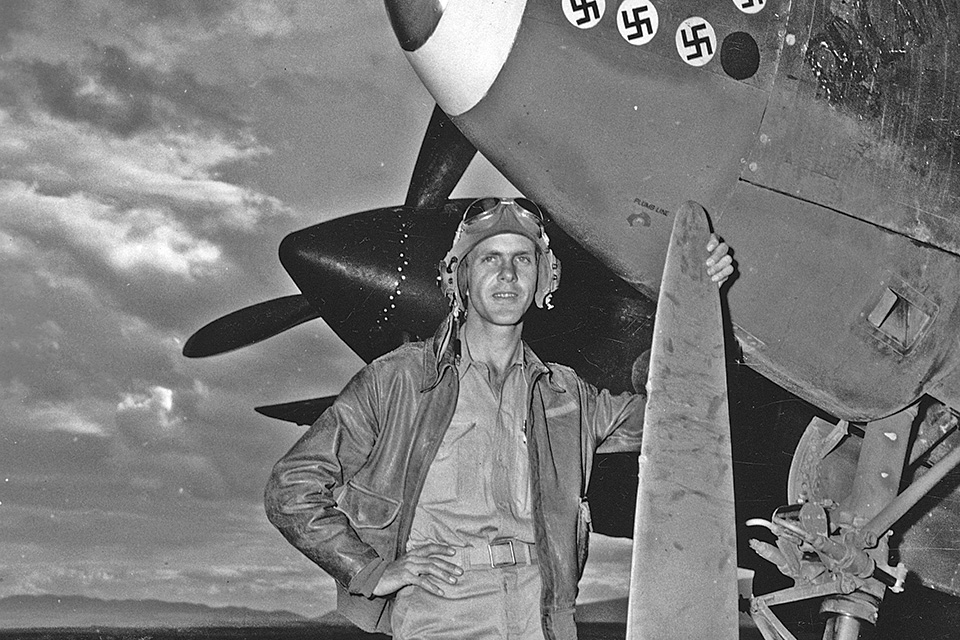

Leverette would later learn from a former squadron mate that the 37th Fighter Squadron had gone into action with 350 rounds of .50-caliber ammunition per gun, rather than the standard 500 rounds. When enough rounds had been expended, causing ammunition to fall below a certain level, G-forces could affect the feed, resulting in a stoppage. In order to alleviate this, some rounds were removed and replaced with wooden blocks at the bottom of ammunition trays. Leverette lamented, “I was credited with 7 Stukas destroyed, or 50 rounds (per gun) per kill, on average. Another 150 rounds (per gun) would have meant another three kills, at least.”

On completion of their mission, all seven P-38s returned to Libya. The depleted Credential Force continued southeast, with Carlisle being towed by Rockwood. Both ships arrived at Alexandria, Egypt, on October 10. The damage to Carlisle was so extensive that it would never again put to sea. As a result of the attacks on Carlisle and Panther, 60 naval officers and ratings had lost their lives and about 55 were injured.

Not surprisingly, Allied accounts were at odds with German sources concerning Luftwaffe losses. Royal Navy gunners believed they had brought down three aircraft. On the American side, Major Leverette was credited with the destruction of seven Ju-87s. Five more were claimed by Lieutenant Hanna and three and a probable by Lieutenant Sprinkle. Lieutenant Blue was credited with a Ju-88, and his wingman, Lieutenant Robert Margison, with one Ju-87. A probable Ju-87 was also credited to Lieutenant Elmer La Rue. Only Lieutenant Thomas “Dub” Smith returned without a victory claim.

According to available Luftwaffe records, however, no more than seven Ju-87D-3s fell to fighter attack southwest of Rhodes, resulting in the loss of all but three airmen. Another Ju-87D-3 of 6/StG.3 made an emergency landing at Rhodes; only the pilot survived. In addition, a Ju-87D-4 and its crew fell to AA fire and a Ju-88A-4 was lost south of Kos, reportedly due to engine trouble. The crew was rescued.

Interestingly, at about the same time that the 37th Fighter Squadron intercepted the Luftwaffe dive bombers, three RAF Bristol Beaufighters of No. 252 Squadron also reached the convoy, only to be attacked from above by three P-38s. One Beaufighter was hit in both engines and the hydraulic system and crash-landed on returning to Cyprus. The crew escaped injury. Could this have been the “Ju-88” claimed by Blue?

The very next day, a warning order was issued for U.S. B-24 and P-38 squadrons on loan from Mediterranean Air Command to stand by to return to Tunisia. The 37th Fighter Squadron arrived back at Sainte Marie du Zit airfield in Tunisia on October 12. For British forces in the Aegean, the loss of these superb machines was a major blow. Air operations would continue, but without suitable fighters providing all-important air cover, the British had little chance of maintaining their presence in the Aegean.

After a five-day land battle, Leros fell to German forces on November 16, 1943. The last major island, Samos, was evacuated and taken without a fight six days later. When it was over, the War Office in London dismissed the Aegean actions as a “minor affair.” That minor affair had cost Britain an entire infantry brigade along with supporting troops and, together with other Allied forces, 20 warships and submarines and about 100 aircraft. According to German records, on Kos and Leros alone, some 13,000 Italians and British were taken prisoner. On both sides, hundreds had perished. The sinking by Allied forces of German transport ships also resulted in the deaths of thousands of Italian prisoners of war.

With the exception of Kastellorizo, the region was now fully under German control. For Italy, the Aegean campaign was the latest in a series of disasters; for Winston Churchill, it would be the last major defeat; for Hitler and Germany, it was a final enduring victory, with some islands remaining in German hands until the end of the war.

Leverette was among those decorated for their role in the October 9 mission. Later, his commanding officer, Lt. Col. Oliver B. “Obie” Taylor, wrote: “Bill’s exploit on this day established what turned out to be a Theatre record, for which he received the Distinguished Service Cross. I tried unsuccessfully to persuade XII Bomber Command that Bill should get the Medal of Honor….Of course the DSC was subject to meeting pretty stiff requirements and something of a rarity itself.”

Lieutenant Homer Sprinkle would die in a flying accident just over a week after the action, on October 18. His remains were later repatriated. On January 16, 1944, Lieutenant Elmer La Rue failed to return from a mission. He is interred at Florence American Cemetery in Italy. It is not certain what became of Dub Smith. But Leverette, Wayne Blue, Harry Hanna and Bob Margison all survived the war, remaining in the service for a good number of years.

British author Anthony Rogers specializes in researching and writing about the Mediterranean theater during World War II. Among his books are Churchill’s Folly and Kos and Leros, 1943, which are recommended for further reading, as is P-38 Lightning Aces of the ETO/MTO, by John Stanaway.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2019 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!