I impress upon you the necessity of action and energy. Follow any trail and all trails of hostile or suspected hostile Indians you may discover and, if possible, overtake and chastise them if unfriendly.

Texas Governor Hardin Richard Runnels dispatched those instructions on Jan. 28, 1858, to John Salmon “Rip” Ford, his newly chosen senior captain of the Texas Rangers, so there would be no mistaking the governor’s desires for an expedition into Comancheria. All through the summer of 1857 Comanche raiders had terrorized the Texas frontier, burning homesteads and killing settlers. Although protection from such raids was a federal responsibility, the U.S. Army was found wanting, primarily because it pitted mounted infantrymen against warriors on fleet Indian ponies. Texas already had state troops in the field, but not enough to patrol the vast frontier line. Rumors had spread the Comanches planned a major invasion. They had mounted such large-scale raids before in Texas, the most infamous being the Great Raid of 1840, when Chief Buffalo Hump’s Comanches fought and burned their way to the Gulf of Mexico.

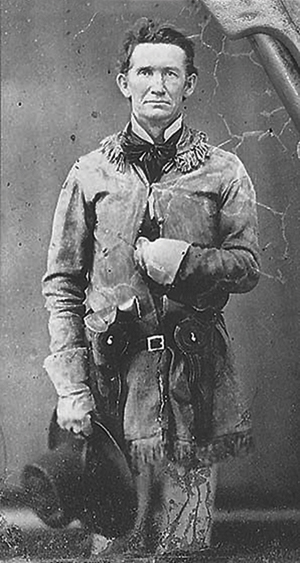

Governor Runnels had decided the only way to check the Comanches was to send Texas Rangers on a preemptive strike over the border into the heart of Comancheria without federal permission. Rip Ford seemed the perfect choice to head such a force. He had fought with the Texas Mounted Rifles during the Mexican War, earning the nickname “Rip” for his habit of scrawling “Rest in peace” beside the name of each deceased when compiling company casualty lists. In 1849 he’d signed on as a captain with the Texas Rangers, and for the next two years his company had fought hostile Indians along the Rio Grande. Ford had then taken a six-year hiatus to pursue political and civilian ventures before Runnels appointed him senior captain of all the Rangers in January 1858, tasking him with running down the Comanches.

Born in South Carolina on May 26, 1815, and raised in Tennessee, John Salmon Ford moved to Texas in 1836, where he practiced medicine and studied law. By 1858 the blue-eyed Ford was a soft-spoken lawyer and newspaper editor who studied the Bible every night and taught Sunday school, though he retained the reputation of a fighting man. His battles against the Comanches had already cost him a finger from his right hand and a wound from a poisoned arrow that still bothered him.

Wanting to give Ford as much of an edge as possible, Runnels requested a supply of newly arrived Colt 1851 Navy revolvers from U.S. Army Brevet Maj. Gen. David Twiggs, commander of the Department of Texas. Twiggs refused, insisting he would not issue the pistols unless Ford’s men were placed under federal command. Federal oversight was the last thing Ford wanted, as he planned to hit the Nokoni band as hard as he could deep in federally controlled Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma)—well outside Texas’ jurisdiction.

To carry supplies and transport the wounded, Ford planned to bring along two light wagons and an ambulance under the command of his formidable 73-year-old father, Ranger Captain William Ford. The younger Ford packed plenty of dry powder and blankets at the expense of foodstuffs. The men would subsist on buffalo and rabbit meat, while the horses would eat what grass they found. Though the party was well armed, from the outset Ford knew he did not have enough men. For the remainder of the winter he made camp near the Brazos Agency—a reservation for the many small bands of Indians still in Texas, then under the supervision of Captain Shapley Ross. His hope was to entice the various reservation tribesmen to march against their mutual enemy come spring. A final necessity was a good scout, one with intimate knowledge of the Comanches and their country. For that he recruited Keechi, who had lived with the Comanches, the Nokonis in particular.

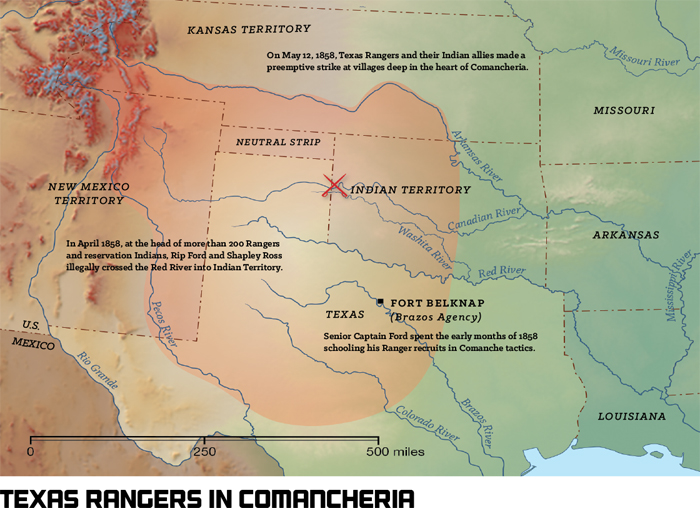

While Keechi was out scouting for the enemy, Ford trained his raw recruits in Comanche tactics. He likely warned them the enemy might feign retreat only to suddenly turn and fight, and that while enemy warriors were adept at firing from horseback, they readily engaged in hand-to-hand combat. Keechi returned to camp in April. He had discovered the Nokoni villages along a bend of the Canadian River near the Antelope Hills. Ford had his target. On April 22 he led his party of 102 Rangers north toward the Red River. At Cottonwood Springs, just south of the river, Captain Ross arrived at the head of a motley group of 113 reservation warriors, representing the Tonkawa, Caddo, Waco, Shawnee, Delaware and Tawakoni nations.

On April 29 Ford crossed the Red River into Indian Territory. He ordered his scouts to fan out anywhere from 15 to 20 miles and patrol in a revolving circle around the party—an early-warning system against surprise attack. Ranging beyond state boundaries without federal permission, Ford’s force was on its own.

As Ford relentlessly pushed his Rangers and their Indian allies north, they passed through buffalo herds and shot and slaughtered enough of the animals to eat well. On May 10 scouts killed a buffalo and were surprised to find Comanche arrowheads buried deep in fresh wounds. They were close, but how close? The next day one of the scouts spied a group of Comanche hunters running buffalo. When the slaughter was over, Keechi stealthily followed Comanche pack animals loaded down with fresh meat. As darkness fell, Ford sent out other scouts to find Keechi, but they could not. Ford had hoped to hit the Comanches in the night, but without Keechi’s intelligence, he would be marching blindly. He feared the Nokonis would find him first.

As light tinged the horizon on May 12, Ford woke his command. The reservation Indians wrapped white cloth bandages around their heads, so the Rangers would not accidentally shoot them in battle. As they did so, Keechi finally rode in to report the location of one small village and a second larger village farther out.

Advancing 6 miles, the Rangers reached the small village of five lodges at 7 a.m., and Ford ordered a charge. As the Rangers rode in, two mounted Comanches raced off toward the larger village. While the Rangers and most of the reservation Indians under Ross took off in pursuit, the Tonkawas stopped to loot, kill and take horses. Riding slightly ahead of the Rangers, their Indian allies forded the river and came on a Tenawa Comanche camp. Some 350 enemy warriors poured from the lodges, prepared to fight. To lull the Comanches into thinking they faced only other Indians, Ford held his Rangers in check just out of sight. He then directed Ross to send their Indian allies against the village.

Leading the Comanches was Po-bish-e-quash-o (Iron Jacket), dressed in his namesake scaled-mail shirt of Spanish origin, which fellow Tenawas believed capable of warding off both arrows and bullets. The chief rode forward from the village and wheeled his mount in full view while screaming in defiance. What he didn’t know was that Ross’ Indians were armed with Mississippi rifles and six-shooters. Iron Jacket charged.

“Kill the son of a bitch!” cried Lieutenant Billy Pitts. A bullet from the first volley hit the chief’s mount, which reared before crashing down dead. Iron Jacket leapt free and rolled to his feet, ready to confront any comers on foot. A second volley knocked the chief back down, while a lone, straggling shot finished him off. The Tenawas were stunned Iron Jacket’s “impenetrable” mail shirt had failed him.

At that moment Ford and Pitts charged into the village with the main body of Rangers, while a detachment raced around to the left of the village to block any escape. Women and children screamed amid the gunfire, and soon the battle devolved into a series of drawn-out hand-to-hand fights stretching over an 18-square-mile area. “Captain Ford,” Sergeant Bob Cotter recalled, “was everywhere, directing and controlling the movements of his men.”

With the Ranger mounts tiring, and the surviving Tenawa warriors on the run, Ford led his men back to the captured village. There he found Ross had drawn up the reservation Indians into battle formation.

“What time in the morning is it?” Ford asked, as he reined in his horse alongside Ross.

“Morning, hell!” said Ross. “It’s 1 o’clock.”

The fight had already raged for six hours, and it appeared more combat lay ahead, for the hills above and to their west were alive with mounted Comanches. Chief Peta Nocona, father of future Comanche Chief Quanah Parker, had heard the gunfire from his nearby village and rushed his warriors to the scene. Many bore shields and 14-foot lances normally used on buffalo hunts.

Suddenly, pistol shots rang out as Private Oliver Searcy dashed in afoot from the west. He and Private Robert Nickles had been chasing fleeing warriors when they ran headlong into Peta Nocona’s men. Searcy said he’d told Nickles to stop and fire now and then to check the Comanches. But Nickles had panicked, turned his back and tried to gallop to safety, only to be run down and lanced to death. Searcy had managed to keep his pursuers in check, intermittently firing and running, before abandoning his horses and following ravines to elude the Comanches.

‘We have nothing up there to fight for! We have some of your women and children captives; also your wigwams, your buffalo meat and your horses! You come down! You have something here to fight for!’

As reservation Indians attended to Searcy, Ross noted Peta Nocona was maneuvering his warriors into a wooded area along the upper slopes of the hills, where Comanche ponies would have a better foothold, and the Rangers would lose their firepower advantage. Ross considered sending up his Indians en masse to dislodge the enemy, but one of his men suggested another tack. Riding out alone, the warrior stopped midway between the Rangers and the enemy and hollered up a challenge to Peta Nocona’s men: “We have nothing up there to fight for! We have some of your women and children captives; also your wigwams, your buffalo meat and your horses! You come down! You have something here to fight for!”

Peta Nocona’s Comanches did come down from the hills, and for a half-hour they engaged the reservation Indians in a fight marked by hurled insults and feint charges on both sides. Here and there a Tonkawa or a Waco would ride out to engage a Comanche in hand-to-hand combat, only to retreat when things didn’t go well. One Waco warrior died on the tip of a Comanche lance. But Ford and the Rangers were compelled to hold their fire, most of the reservation Indians had removed the white bandages that distinguished them from the enemy, claiming the bright cloth made them easy targets for Comanche marksmen.

While the Indians clashed, Ford divided his Ranger force, sending a detachment under Lieutenant Allison Nelson to circle behind the Comanches and cut off their retreat. He then had his bugler recall the reservation Indians. As they cleared the line of fire, Ford ordered Pitts to charge the enemy. But Tonkawas under Placido galloped in prematurely to support Nelson’s force, kicking up dust that drew Peta Nocona’s attention. Recognizing the trap, the Comanche chief quickly led his warriors from the field. Pitts’ men kept right on the Comanches’ heels, and Ford had difficultly recalling them. “They wanted more blood,” Ford reflected years later.

By then it was 2 p.m. Ford’s men were running low on ammunition, and their horses were nearly spent. Furthermore, an elderly female captive told Ford’s scouts that a dozen miles downriver was a larger Comanche camp under Chief Buffalo Hump. Ford ordered the captured Tenawa village burned and his force back to the supply wagons before more Comanches arrived to help their fellow tribesmen. As the Rangers pulled out, Ford noticed many of the Comanche corpses were missing hands and feet. The Tonkawas had strapped the gruesome trophies to their saddles so they might feast later on something besides buffalo meat.

The Rangers and their allies, with 16 captives in tow, reached the supply wagons by dusk. There, much to the astonishment of the Texans, the Tonkawa sat down for their meal of human flesh. One of the Rangers asked Tonkawa Chief O’Quinn in jest, of all the nationalities he had tasted, which he preferred. The war chief recalled “a big, fat Dutchman” he and his men had killed on the Guadalupe River in 1849. Bugler Billy Holzinger took the answer as a slur against his German countrymen from Texas Hill Country and drew a pistol, challenging O’Quinn. Ford rushed in to intervene before gunfire erupted between the Rangers and Tonkawas.

Ford began his return march to Texas on May 13. One supply wagon after another broke down as the Rangers made their way to the Red River. But they arrived safe and sound at the Brazos Agency on May 20. Ford had led his force some 500 miles through hostile territory, fought Comanches over seven hours—in what became known as the Battle of Little Robe Creek or Battle of Antelope Hills—killed 76 of them and captured more than 300 of their horses. He lost only two men, Nickles and the Waco warrior, both lanced to death. Though denied the use of the new Colt revolvers, Ford’s Rangers had been formidably armed, and they had employed such proven tactics as living off the land, attacking at dawn and waging a scorched-earth offensive—strategies the U.S. Army would turn to in its Western Indian campaigns after the Civil War. WW

Mike Coppock writes often about the American West for Wild West and other publications. Recommended for further reading: Rebellious Ranger: Rip Ford and the Old Southwest, by William J. Hughes; Rip Ford’s Texas, by John Salmon Ford; and The Texas Rangers, by Walter Prescott Webb.