The nadir of Nazi-era depravity was the concentrated effort to employ death camps to eliminate from Europe those who did not fit into the perverted notion of Aryanism. But over the past 70 years another aspect of that Hitlerian campaign has gotten little attention: the formal effort to wipe out the cultural imprint of Nazi-targeted people by looting and destroying the records of their histories and deliberations.

The Jews were the first targets, but libraries of Freemasons, socialists, communists, and Catholics were also looted. As the Germans conquered Eastern European countries, the Nazis added Slavs to the list. They confiscated millions of books and documents to stock German research institutions, and simply torched hundreds of millions more. Only a small portion of the institutional holdings got back to their homes; now a very few personal volumes are being returned to their owners or their heirs.

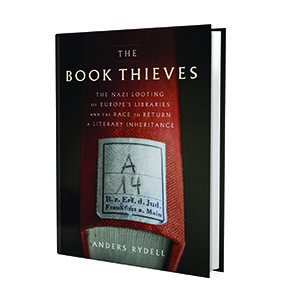

The Book Thieves, first published in Sweden in 2015 and now available for the first time in English, shines a light on the German campaign against the written word. “It was not solely a war of physical extermination, it was also a battle for memory and history,” Swedish journalist Anders Rydell writes. “The plundering of libraries and archives went to the very core of this battle for control of memory.” For the past decade, a few scholars have been charting this destruction of literature, but The Book Thieves is the first to present these events to the general public.

Much of the German military and civilian population was behind the wanton destruction of books. Their confiscation, however, was primarily the effort of two rival powers battling over the spoils: Heinrich Himmler’s SS, which was mostly interested in information that helped the Nazis better understand their enemies, and chief Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg’s special task force, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, or ERR, which sought after useful research materials proving Germanic superiority.

Rydell writes well; nonetheless, this is not an easy read. The book is organized city by city following Rydell’s travels throughout Europe, a construction that inevitably leads to repetition. And the author is so intent on providing the historical setting for the book collections in each city—his 15-page chapter on the Grecian city Thessaloniki does not mention the attack on its library until the ninth page—that it often obscures the story’s main thread.

But Book Thieves tells an important story and readers interested in understanding the full impact of the inferno Germany unleashed in World War II would do well to read Rydell’s tome.

—Daniel B. Moskowitz is a veteran journalist and frequent contributor to World War II.

This review was originally published in the May/June 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.