[dropcap]A[/dropcap]dvanced technology weapons” and the “Confederate military effort” are phrases seldom found used together. Indeed, the South’s many disadvantages resulting from its primitive weapons-manufacturing infrastructure, compared with the highly industrialized North’s prolific arms factories and government-run arsenals, are typically cited as a principal reason the Union ultimately triumphed. Although the Confederates created the world’s first practical submarine, H.L. Hunley—which famously sank USS Housatonic on February 17, 1864—that example of cutting-edge technology tends to be treated as a “one-off” success, due more to luck and late-war desperation than to a commitment of resources to weapons technology.

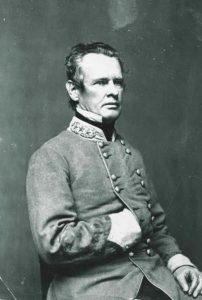

Yet the well-worn view that the “primitive” South hopelessly struggled against the “technologically superior” North is demonstrably flawed. Not only did the Confederacy have forward-thinking technocrats who created “futuristic” weaponry, it also produced at least one visionary weapons genius: Gabriel James Rains. That officer’s inventions and his practical application of them on Civil War battlefields justly earn him the title of “the father of modern mine warfare.” The approach he instituted during the war still confounds military forces on 21st-century battlefields.

At daybreak on May 4, 1862, “cruel murder” took place in the streets of Yorktown, Va., as Federal troops encountered enemy land mines, or torpedoes, for the first time. The mines had been carefully planted in select locations during the night by Yorktown’s Confederate commander, Brig. Gen. Gabriel J. Rains. Yorktown had been the focus of a month-long siege by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Federal forces in the early stages of the Peninsula Campaign. Although Rains and his brigade—made up of the 13th Alabama, 26th Alabama, 6th Georgia, and 23rd Georgia—had held out admirably during the siege, by the end of April the Confederate high command desired the formation of a new defensive line closer to Richmond.

Rains accepted the order to evacuate, but he was unwilling to pass up a chance to impede any enemy pursuit. On the night of May 3, Rebel soldiers began slowly moving through the mud out of the Yorktown garrison, heading to Williamsburg. A small unit remained behind and kept up a constant fire as their comrades evacuated. Soon Rains sent a staff officer back to Yorktown to guide his heavy artillery battalion to safety—a delicate task due to the metal primers for igniting concealed armament that dotted the landscape. At 1:30 a.m. the remaining members of the garrison left as well, cautiously following the guide “in single file” along a darkened road to avoid the torpedoes. At least one of those soldiers clearly didn’t approve of the tactic. “This is barbarism,” he said as he emerged from the danger zone.

Union soldiers and cavalry began advancing toward the empty Rebel works later that morning. After a long and tedious siege, McClellan’s forces had finally pushed the enemy back and gained important ground. The heavy Confederate guns of Yorktown and Gloucester Point, guarding the York River, no longer sounded; artillery shells no longer filled the air; and rifle fire no longer came from the trenches. Yet within a few hours, periodic explosions disturbed the quietness of the old surrendered city, as unsuspecting men and horses trod upon Rains’ “farewell gifts.” Among the victims was a telegraph operator. His legs were torn apart after he stepped on an object concealed at the base of a telegraph pole, and he soon died.

The broken ground, as well as word from soldiers involved in early explosions, quickly spread alarm. Men began to cautiously examine the road as they moved on, looking for the “fatal iron fuses, whose touch is death.” Sentinels were soon posted at both suspected and revealed mined positions. The mines were common powder-filled mortar shells with a detonating primer added, what became known as a booby trap. Detonation was of two forms—direct contact with the friction primer of a buried shell or movement of an article that was attached to the primer by means of “concealed strings or wires.” Many innocent-looking objects (common work tools, for instance) became triggering devices.

Finally at about 11 a.m., the 44th New York Infantry entered Yorktown, with its band playing and flags flying. Lieutenant George Herenden was directed to take a detail of approximately 25 men to the Confederate prison within the fort and have them dig up torpedoes. Approximately 50 would be exhumed without accident.

For the first time in the war, human suffering was the product of “villainously concealed” weapons rather than hand-to-hand combat. One observer that morning, noted political scientist and Columbia College professor Francis Lieber, watched in horror and disbelief at the grim sight of Rains’ “infernal machines” along the streets, beneath trees, and at the bases of telegraph poles tearing the earth and spitting fire and fragments into the air. For Lieber, a German native in his 60s who had fought in and been wounded at the Battle of Waterloo, this was simply unconscionable. The following April, at Abraham Lincoln’s behest, he published the Lieber Code dictating the so-called “Laws of Warfare.”

Rains, born in New Bern, N.C., in 1803 was not a typical military man. Most skilled generals of this period were infantrymen who recognized the importance of mass concentrations of men on the field of battle. They also knew that the war would be won by foot soldiers and to that end they studied closely Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics, as they pushed their men toward strategic points and enemy forces. But while many commanders devotedly followed this 1855 manual by future Confederate General William Hardee, Rains waged war in an unconventional manner. His maxim: “Deception is the art of war.” Risking disapproval, he adhered faithfully to this dictum.

Nevertheless, Rains’ unorthodox weapons, though effective, were harshly criticized not just by his Northern enemies, but also some of his Southern compatriots, among them Generals Joseph E. Johnston, James Longstreet, and Moxley Sorrel. In a post-Yorktown letter to Rains, Sorrel sniffed that mines and booby traps were not the weapons with which “gentlemen” fought wars. Longstreet in turn wrote to Rains insisting that he cease such activity.

Their umbrage comes across as somewhat puzzling, given that tunneling beneath enemy fortifications and planting subterranean mines to be exploded remotely was conducted at Vicksburg’s 3rd Louisiana Redan in June 1863 and at Petersburg’s Crater in July 1864. Apparently in siege warfare, widespread destruction via such mines was perfectly acceptable, but Rains’ smaller-scale, shrewdly concealed mines and booby traps were not. Rains, however, persevered in developing his alternate weapons for land and sea warfare, ignoring the censure of the “gentleman cavaliers” running the Confederate war effort.

George McClellan referred to these precursors of modern land mine warfare as “murderous and barbarous” and typically ordered Confederate prisoners of war to remove them. Although Rains’ land mines are now accepted weapons of war, the use of POWs to remove them definitely is not, according to the Geneva Convention.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Rains waged war in an unconventional manner. His maxim was ‘Deception is the art of war’[/quote]

Excelling in engineering, chemistry and mathematics, Rains graduated from West Point in 1827, served in the Second Seminole War, and on July 31, 1861—by then a lieutenant colonel with 34 years’ service—resigned from the U.S. Army to join the Confederacy. After a series of troop commands, which included leading the spring 1862 defense of Yorktown featuring his innovative land mines, Rains was assigned in June 1862 to command the “submarine defenses of the James and Appomattox Rivers.” Applying his land-mine technology to river and sea avenues of approach, Rains developed his underwater “torpedo” and in December 1862 was appointed CSA Torpedo Bureau superintendent.

Below are some of Rains’ inventions, which led to the development of modern torpedoes, mines, and improvised explosive devices (IEDs):

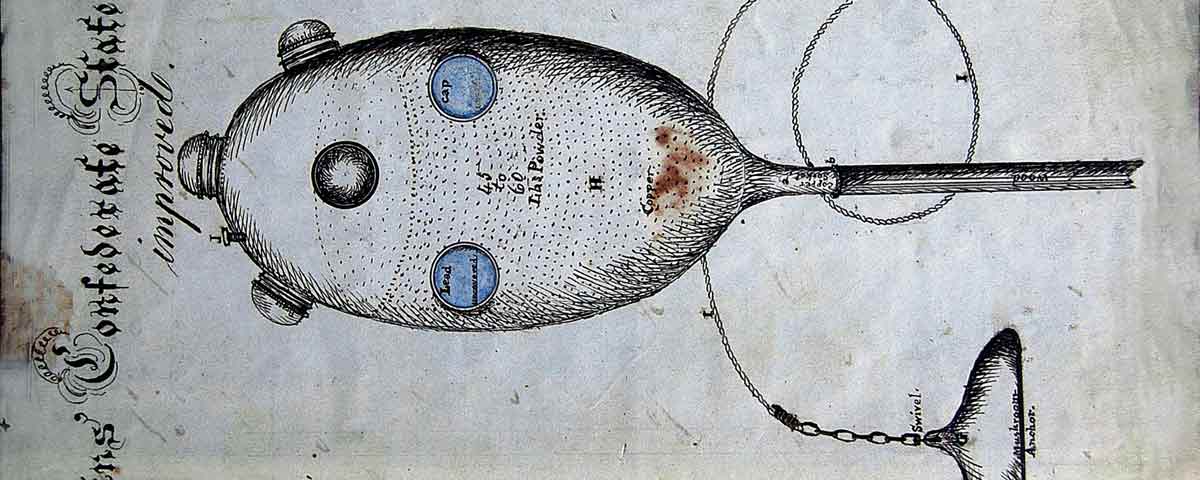

Sensitive Primer

The sensitive primer used a percussion device containing potassium chlorate, sulphuret of antimony, and pulverized glass. The primer was capped with a thin cover of copper that could be crushed with 7½ pound per square inch of force. Crushing the cover caused the primer to detonate, and the resulting concussion and fire caused the rest of the explosive trail, consisting of a match made of gunpowder dissolved in alcohol, to ignite and set off the main charge. The primer was used in:

➤ Subterra shells (land mines)

➤ Barrel torpedoes (floating and moored sea mines)

➤ Frame torpedoes (bottom sea mines)

➤ Spar torpedoes (torpedoes used by vessels)

➤ Dart grenades (dart-shaped hand grenades)

When the primer was used in water, the copper caps were used; for land applications, the lead cover was used. After the primer was manufactured, a safety cover was installed to prevent accidental crushing of the thin cover by striking or dropping. This safety cover was removed when the weapon was put into action. Another feature of the weapon was a hexagonal nut used to screw the primer into place. The hex was nonstandard and therefore required a special wrench. If the weapon fell into enemy hands it would be difficult to disassemble.

Subterra Shells

Perhaps Rains’ most unique invention was what he called the “subterra shell.” This, in effect, was the first land mine to be used in large-scale warfare. The first instance of its use occurred when Rains was serving in Florida during the Second Seminole War. To avoid the need to have a permanent lookout on duty at all times, Rains booby-trapped a dummy resembling a soldier’s body. The day it was planted, an explosion was heard in the army camp. When the soldiers returned to the place where the dummy had been, they found that the shell had been exploded by an animal found dead at the scene.

As Confederate forces conducted a tactical retreat from Yorktown during the Peninsula Campaign, Rains’ men used leftover powder to construct subterra shells and planted them in some redoubts, at the powder magazine, and near the telegraph office. A Union signal man working near a telegraph pole tripped a mine, causing a thunderous explosion that threw his body some 15 feet and stripped his clothes completely off. Four of these weapons were later planted on the Richmond Road, about five or six miles north of Williamsburg, Va. These weapons were triggered by Union cavalry with devastating results. The Union Army was delayed three days while deliberating whether to continue on a possibly mined road or use some other route. Union officers finally chose the other route.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Mines and booby traps were not the weapons with which ‘gentlemen’ fought wars[/quote]

After use of subterra shells at Yorktown, Brig. Gen. Moxley Sorrel admonished Rains that subterra shells and booby traps were not the way that “gentlemen” fought wars. Later, the Confederacy would deem these weapons acceptable. They were used to impede Ulysses Grant’s march from Vicksburg to Jackson, Miss.; at South Carolina’s James Island, which protected Fort Wagner; at Fort McAllister, Ga; and at Mobile’s Spanish Fort, which didn’t capitulate until the final days of the war.

In a report to the Confederate War Department dated November 18, 1864, Rains stated that as of that date 1,298 subterra shells had been planted near the ring of defenses around Richmond. These weapons created a field some 40 feet wide in front of the parapets and forts strung around the eastern side of the capital, from Fort Hoke to Fort Alexander, including Forts Harrison, Beauregard, and Johnston. The field was marked with red pennants attached to stakes driven into the ground beside the shell. Where there was a path for pickets to cross the field, there were stakes of a different color, and provisions for lanterns on the ground near the shells, shielded so that they only shone back toward the Confederate lines.

Barrel Torpedo

Barrel torpedoes were the most popular type of underwater weapons used by the Confederacy and were employed in all saltwater operations. The Rains primer, with its copper cover, provided a noncorrosive, waterproof triggering device for these weapons. The tower was fabricated from beer-, nail-, powder-, and other barrels or kegs, which were coated with pitch to improve their water tightness. The cone-shaped ends helped stabilize the weapon in the water and provided the added buoyancy for the 60-pound explosive charge, made up of chlorate of potash, prussiate of potash, white sugar, and red lead. They were used in the James River early in the war, at Charleston, and in the surrounding rivers, together with submarine mortar batteries. They were also used in Winyah Bay, S.C., in the Cape Fear and Roanoke Rivers in North Carolina, at Savannah, in Mobile Bay, and in New Orleans. Several variations were implemented in different locations, under different conditions. These varied in the number and placement of primers and the way in which others were attached to their anchors. Some were anchored and fixed in one spot, while others were anchored so that when linked together they would be drawn to a ship that passed between them.

Submarine Mortar Battery

Another invention by Rains, used extensively in Charleston, the Ogeechee River in Georgia, and as a single unit in Mobile Bay, was the submarine mortar battery. This was a structure 60 feet long and 35 feet wide, built of timber. Once assembled, it was towed into position and the 35-foot edge was moored to the bottom with mushroom anchors. The device angled up from the bottom, so that when four artillery shells were attached upright on the free end of the 60-foot logs, they would be at the right depth to touch the submerged part of the hull of a passing ship.

These were used in the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, in the Hog Island Channel, and in other areas of Charleston Harbor. They effectively closed the harbor to Union ships for a substantial period, preventing the taking of the city by sea. Rear Admiral John Dahlgren’s men found several of the submarine mortar batteries intact, and evidence of others that had deteriorated due to worm attacks on the unprotected wooden parts of the structure.

Spar Torpedo

Rains’ fuses were also used in spar torpedoes, aptly named because they were mounted on the end of a long spar or pole that was then thrust outward from the craft carrying the torpedo so that it touched the hull of the target vessel. The torpedo itself was a cylindrical-shaped device, with provisions for installing multiple fuses in one end, and having a socket attached to the other end to accept a pole called a spar. The spar was supposed to be of sufficient length to allow a safe “stand-off”—meaning the torpedo’s charge would explode at adequate distance to avoid damaging the craft delivering the torpedo. The actual charges in spar torpedoes ranged from 30 to 100 pounds of black powder. In cases where the spar torpedo used Rains’ fuse, the spars were 30 feet long and were carried on 37- to 50-foot long boats. Since the boats had to approach the target vessel to within the length of the spar, utmost stealth was required. Most attacks would be at night and against moving ships. On February 17, 1864, in history’s first submarine sinking of an enemy warship, H.L. Hunley sank USS Housatonic with a spar torpedo, though it too sank in the process.

Room & Military Museum)

Southern Accents

The South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum (crr.sc.gov) and the South Carolina Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans have embarked on a major project to conserve the museum’s collection of Confederate uniforms, including one that belonged to Gabriel Rains. In all, the museum hopes to conserve about 15 uniforms, with Rains’ the first, according to W. Allen Roberson, the museum’s executive director.

Among the other uniforms in line are one belonging to Colonel Elbert Bland, of the 7th South Carolina Infantry, who was killed at Chickamauga; and a coat that belonged to General James Chesnut, husband of famed diarist Mary Chesnut. Roberson says the coat in their possession is believed to be the one Chesnut wore to accept Fort Sumter’s surrender from Major Robert Anderson in April 1861.

The restoration of Rains’ coat by the Textile Conservation Workshop in South Salem, N.Y., is expected to take several months and will include fumigation, several cleaning processes, patching holes, encapsulating the piping to deter further fraying, and replacing six missing buttons. Upon the uniform’s return later in 2018, the museum will exhibit it for the first time in more than 20 years. The museum staff hopes to plan a larger exhibit when conservation work on the full collection is completed.

Previously, the South Carolina Sons of Confederate Veterans helped the museum raise over $111,000 to conserve 11 Civil War Confederate company flags displayed in an award-winning exhibit, “Bold Banners: Early Civil War Flags of South Carolina” in 2011. The first of five South Carolina Civil War Sesquicentennial exhibits, it won the South Carolina Federations of Museums’ 2012 Award of Achievement for that year. –Melissa A. Winn

Dart Grenade

Rains adapted his primer to a land device he called a dart grenade, a Confederate version of William Ketchum’s widely used “Improved Hand Grenade.” When the striker hit an object, the impact moved the striker against the musket primer cap, setting it off and igniting the main powder charge. Edward Porter Alexander, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s chief of artillery, wrote in his posthumously published book Fighting for the Confederacy:

“I also sent to Richmond to have a large lot of hand grenades made of a pattern which Gen. Rains had recently devised. They were thin, iron-shells, about the size of a goose egg with powder and a sensitive paper percussion fuze in the front and a two foot strap or strong cord to the rear end. A man could swing one of these and throw it 60 yards and they would burst wherever they struck. I sent for these, believing that the enemy were preparing to make a regular siege approach, upon Elliot’s Salient…”

The grenade shells were provided with the percussion cap, but powder was not poured into the shell until the grenade was ready for use. After the powder was instilled, the tail was assembled. The dart grenade had a lanyard, but its function was to pull a safety pin that held a cover in place over the Rains primer on the nose of the grenade. Dart grenades could be filled with powder at the manufacturing plant and transported as a complete unit, with the tails packed separately. The cover of the primer, in the nose, would keep the weapon safe during handling and shipment. The tail had fins made of feathers, looking like darts (thus the name). When thrown, the grenade would not explode until its nose made impact with its target. Since the impact pressure only had to be approximately 7½ pounds per square inch, the object hit did not have to be too solid.

This weapon also had the virtue of dual capabilities. With the tail removed, it could be buried and used as a land mine. Being much smaller than the subterra shell, it was effective against foot soldiers and horses, while the subterra was most effective against cavalry, wagons, and towed artillery. Officers sent by Rains from the Torpedo Bureau in Richmond, to Columbia, S.C., to slow Sherman’s advance recommended that these dart grenades be used as land mines in place of subterra shells. They were also used as grenades in the Confederate defensive lines around Petersburg.

Safety Valve

After the war, Rains became interested in steam propulsion and designed a boiler safety valve that received a U.S. patent and earned him recognition as a non-military inventor. The valve differed from those in operation at the time because it used a portion of the boiler’s steam pressure to complete the opening of the valve. It would not be a commercial success for him during his lifetime, however.

Gabriel Rains was primarily a scientist and not a military man. The inventions of his chemical fuse, with its safety cover, improved the safety in handling and transport for torpedoes and grenades. He was able to extend the useful life of torpedoes in saltwater and was the first to create fields of torpedoes as barriers to ship transit. His contribution to the ordnance community was as manifest as the invention of the ironclad to the Navy.

His position in the Confederacy gave him the freedom to develop his talents to the fullest. Although not a dashing commander in the field, he was an excellent engineer, capable of reinforcing earthworks and other defensive positions, and he was able to develop tactics for the weapons he designed. He operated mostly in obscurity, however, as the use of mines was still a secretive business.

Despite censure, Rains forecast and embraced vast changes in war technology with chilling accuracy. His devices, such as the land mine, the booby trap, the barrel torpedo, and the “submarine mortar,” were later refined and played decisive roles in future conflicts.

In 1961 Lt. Gen. James M. Gavin, a paratroop commander in World War II, wrote: “Rains was a genius at devising new and deadly ways to blow up Northerners,” noting that Rains’ naval weapons were “so effective…the Federal Navy was forced at last to invent minesweepers.”

Unquestionably, Gabriel J. Rains must be acknowledged as a man of military vision, whose work not only contributed heavily to the defense of the Confederacy, but continues to have a global impact on modern military tactics.

Adapted with permission from Gabriel Rains and the Confederate Torpedo Bureau, by W. Davis Waters and Joseph I. Brown (Savas Beatie, 2017).

Now retired, W. Davis Waters worked for 33 years at the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, and served as site manager at Historic Edenton and at Bennett Place. The late Joseph I. Brown worked for 31 years at the Naval Mine Engineering Facility in Yorktown, Va., and helped design the MK25, MK52 and MK55 mines. He also attended the Naval Mine School in Charleston, S.C.