“There was no part of the bloody field of Sharpsburg which witnessed more gallant deeds of both attack and defense than did the Burnside Bridge,” wrote William Allan, historian of the Army of Northern Virginia. “The 500 Federal soldiers who lay bleeding or dead along the eastern approach to the bridge were witnesses to the courage of the assaults.”

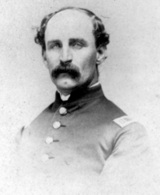

Four days later, the 33-year-old second lieutenant of Company K, 51st New York Volunteer Infantry, one of the two Union regiments that successfully stormed the Rohrbach Bridge across Antietam Creek on the afternoon of September 17, 1862, wrote home to reassure his mother that he had survived the carnage and continued to be “well and hearty.”

“As soon as we were ordered forward we started on a double quick and gained the position, although we lost quite a number of men doing it ” wrote George Washington Whitman, whose older brother, Walt, had already gained a reputation as the rather unconventional author of Leaves of Grass. “As soon as the rebels saw us start on a charge,” George Whitman recounted in a manner that reads almost like the after-action report of a seasoned officer, “they broke and run and the fight at the bridge was ended.”

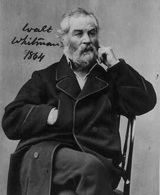

In less than three years, Walt Whitman would publish Drum Taps and Specimen Days, impressionistic volumes that would cement his reputation as the Civil War’s most literary memoirist. George Whitman all but disappeared from history, living in Camden, New Jersey, and working for many years as inspector of iron pipes for the Metropolitan Water Board of New York. He retired to a farm outside Burlington, where he died on December 20, 1901, nine years after his illustrious brother.

And yet, except for a couple of forays to Virginia battlefields after the fighting was over, Walt Whitman never got closer to the war than the military hospital wards in Washington, D.C. But George Whitman served with distinction with the 51st New York for nearly four years. He saw action with the Army of the Potomac’s IX Corps on many of the war’s bloodiest killing fields, including Roanoke Island, New Bern, Second Bull Run, Chantilly, South Mountain, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Vicksburg, Knoxville, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse, the North Anna campaign, Cold Harbor and the Siege of Petersburg.

Along with most of his regiment, Whitman was captured on September 30, 1864, at Poplar Grove Church, Virginia. He spent time in Richmond’s notorious Libby Prison and was later transferred to the military prison hospital at Danville. While a prisoner, Whitman’s personal effects were sent to his family, including a matter-of-fact diary he had kept during the first two years of the war. Walt Whitman read the diary and concluded, “It does not need calling in play the imagination to see that in such a record as this lies folded a perfect poem of the war … ”

Along with most of his regiment, Whitman was captured on September 30, 1864, at Poplar Grove Church, Virginia. He spent time in Richmond’s notorious Libby Prison and was later transferred to the military prison hospital at Danville. While a prisoner, Whitman’s personal effects were sent to his family, including a matter-of-fact diary he had kept during the first two years of the war. Walt Whitman read the diary and concluded, “It does not need calling in play the imagination to see that in such a record as this lies folded a perfect poem of the war … ”

Beyond the impact George’s war service had on his brother’s writing, the letters and diary are the clear, dispassionate observations of a mature, educated Union soldier. No less an authority than the late Bell Irwin Wiley has concluded that “his comments are not only insightful and interesting in themselves, but they provide good grist for accurate history.”

Like many recruits, Whitman went to war to save the Union, not necessarily to free the slaves. He also believed the war would be a short one, enlisting for 100 days with the 13th Regiment of the New York State Militia. His first “well and hearty” letter to his mother was sent from Camp Brooklyn near Baltimore, Maryland, on June 28, 1861. “This city is a regular secession place,” Whitman wrote, “as we walk through the streets in the city the Women and children make a regular practice of saying as we pass them hurah for Jeff Davis.”

More than half of Whitman’s militia regiment reenlisted for three years service when it became clear after the First Battle of Bull Run that the war might be a long one. He joined the 51st New York Infantry, known as the Shepard Rifles, on September 8, 1861—and, because of his age and previous service, was promoted to sergeant major by the regiment’s first colonel, Edward Ferrero, a New York City dancing instructor.

Whitman’s first letter from a war zone arrived home while he was as part of a Union expeditionary force under Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside. It recounts the misery of being cold and wet after two weeks on a crowded troop transport and then storming ashore on Roanoke Island. “We had to wade about 200 yards through mud and water up to our knees … we built fires and tried to dry ourselves as well as we could, took our suppers of hard crackers and then laid down for the night.”

Whitman’s first letter from a war zone arrived home while he was as part of a Union expeditionary force under Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside. It recounts the misery of being cold and wet after two weeks on a crowded troop transport and then storming ashore on Roanoke Island. “We had to wade about 200 yards through mud and water up to our knees … we built fires and tried to dry ourselves as well as we could, took our suppers of hard crackers and then laid down for the night.”

But Whitman’s war diary, probably never meant to be read by anyone but himself, provides details about his first combat experiences in the malarial swamps of that North Carolina barrier island that he didn’t want to share with his family, least they worry about him unnecessarily. “About 6 O clock on the morning of Feb 18th the whole force left in line and commenced to move forward … soon the wounded began to be brought by us, on their way to the rear, and things began to look a little like war.”

By the time the Burnside Expedition brought the war to New Bern, North Carolina, on March 14, 1862, Whitman was an experienced warrior with a veteran’s matter-of-fact way of informing loved ones about death and dying in battle. “Our regt went into the fight with about 650 men and as we lost about 100 in killed and wounded you may know that we had pretty hot work. One young fellow (Bob Smith Orderly Sergt of Co B.) that was killed lived in Portland Ave (in one of the brick houses below the vacant lots I think) … and was a good fellow and an intimate friend of mine.”

Despite regularly being in the thick of “pretty hot work,” Whitman managed to remain unscathed until a fragment of a percussion shell cut through his cheek at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, a Union disaster in which the 51st New York lost 69 officers and men killed and wounded. In a letter from camp near Falmouth, Virginia, on December 16, 1862, three days after the battle, his almost casual reference to his wound, the hallmark of a seasoned veteran, belies the ferocity of the fight he was in. “We have had another battle and I have come out safe and sound, although I had the side of my jaw slightly scraped with a piece of shell which burst at my feet.”

But in a later letter to his brother, Thomas, Whitman was much more candid about the fighting at Fredericksburg. “It was a mighty warm place we were into when I was hit, as the Rebs had a battery planted right in front of us and not more than 1000 yards distance, and they poured grape and cannister into us like the very devil,” Whitman confided, “the range was so short, that they threw percussion shels into our ranks, that would drop at our feet and explode killing and wounding Three or four every pop. It was a piece of one of that kind of varmints that struck me in the jaw.” He concluded by bitterly observing that “we have been most terribly outgeneraled … all we want is some one competent to lead, to finish up this work in short order.”

Whitman found the competent leadership he was looking for when the IX Corps went west to support Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s campaign to capture Vicksburg, the Confederate bastion on the Mississippi River. In a July 23, 1863, letter to his mother, Whitman admitted being in “about as hard a campaign of 19 days as I want to see.” He also recognized that a different type of hard war was being waged in the West. “The western armies burn and destroy every thing they come across,” he wrote, “and the same number of men marching through the country, will do three times the damage of the army of the Potomac.”

Like many men in the ranks, Whitman was contemptuous of the “wire pullers” back home who avoided military service and was furious about the New York City draft riots on July 13–15, 1863. “We have had full accounts of the proceedings of the mob in New York and its almost enough to make a fellow ashamed of being a Yorker,” Whitman confided to his brother Jeff, “what a pity it is that 4 or 5 of the old regts, had not been there to straightened (sic) things up a good bit … as for myself I would have went into that fight with just as good a heart as if they had belonged to the rebel army.”

The IX Corps returned to the Army of the Potomac after successfully defending Knoxville against General James Longstreet’s 12-day siege in November 1863. Whitman, now a captain, went home to Brooklyn on a 30-day reenlistment furlough. By April 1864, he had rejoined his regiment for some of the toughest fighting of the war. As the regiment passed-in-review through Washington on its way to the Virginia front, Walt walked beside his brother and, in an April 26 letter to their mother, recounted that George was so preoccupied talking to him that the soldier failed to salute the balcony holding President Abraham Lincoln and General Burnside.

For the next five months, Whitman and the 51st New York were where the action was hottest. “We had a pretty hard battle on the 6th,” Whitman concluded with almost casual understatement about the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5–6. “Our Regt suffered severely loseing (sic) 70 killed and wounded. I lost nearly half my Co. but we won the fight and the rebel loss was pretty heavy.” Whitman shrewdly observed that, in spite of the heavy casualties, “The Army is in first rate spirits,” In fact, amid the filth and the heat of the trenches before Petersburg, Whitman reassured his mother that “we all believe in Grant, and as far as I can hear the opinion is universal in the army.”

Whitman was front-and-center for one of the war’s most spectacular battlefield failures, the explosion of a gigantic mine beneath the Confederate trenches surrounding Petersburg on July 30 that became known as the Battle of the Crater. “I think it was the most exciting sight I ever saw,” he admitted to his mother. Whitman’s detailed description of the fighting in that horrid pit easily ranks with any historical account of that desperate battle. “I tried my best, to keep the men from falling back … The rebel charge was one of the boldest and most desperate things I ever saw, but if our men had staid there and fought as they ought, we could have inflicted a heavy loss on the enemy before they could have driven us away from there.”

In an August 1864 letter, Whitman included a copy of the report submitted by the regiment’s acting commander, Captain John C. Wright, after the Battle of the Crater. “The Command of the Regiment then devolved upon Captain George W. Whitman, the next Senior Officer,” Wright reported. “I am happy to say he distinguished the duties of the responsible position to my entire satisfaction, and it affords me great pleasure to speak of the gallant manner in which he has sustained himself during the entire campaign.”

George Washington Whitman was an exceptional soldier and a natural leader of men. Like so many other veterans, his wartime experiences proved to be the high point of his life. At the end of the war, he even sought, unsuccessfully, a commission in the Regular Army. Had it not been for the fame of his poet-brother, Whitman’s descriptive letters might have disappeared from history. As it is, they remain as eloquent testimony to a generation of men for whom uncommon valor was a common virtue.

About the Author:

A retired civil servant, Gordon Berg is past president of the Civil War Round Table of the District of Columbia. His articles and book reviews appear in America’s Civil War and Civil War Times.