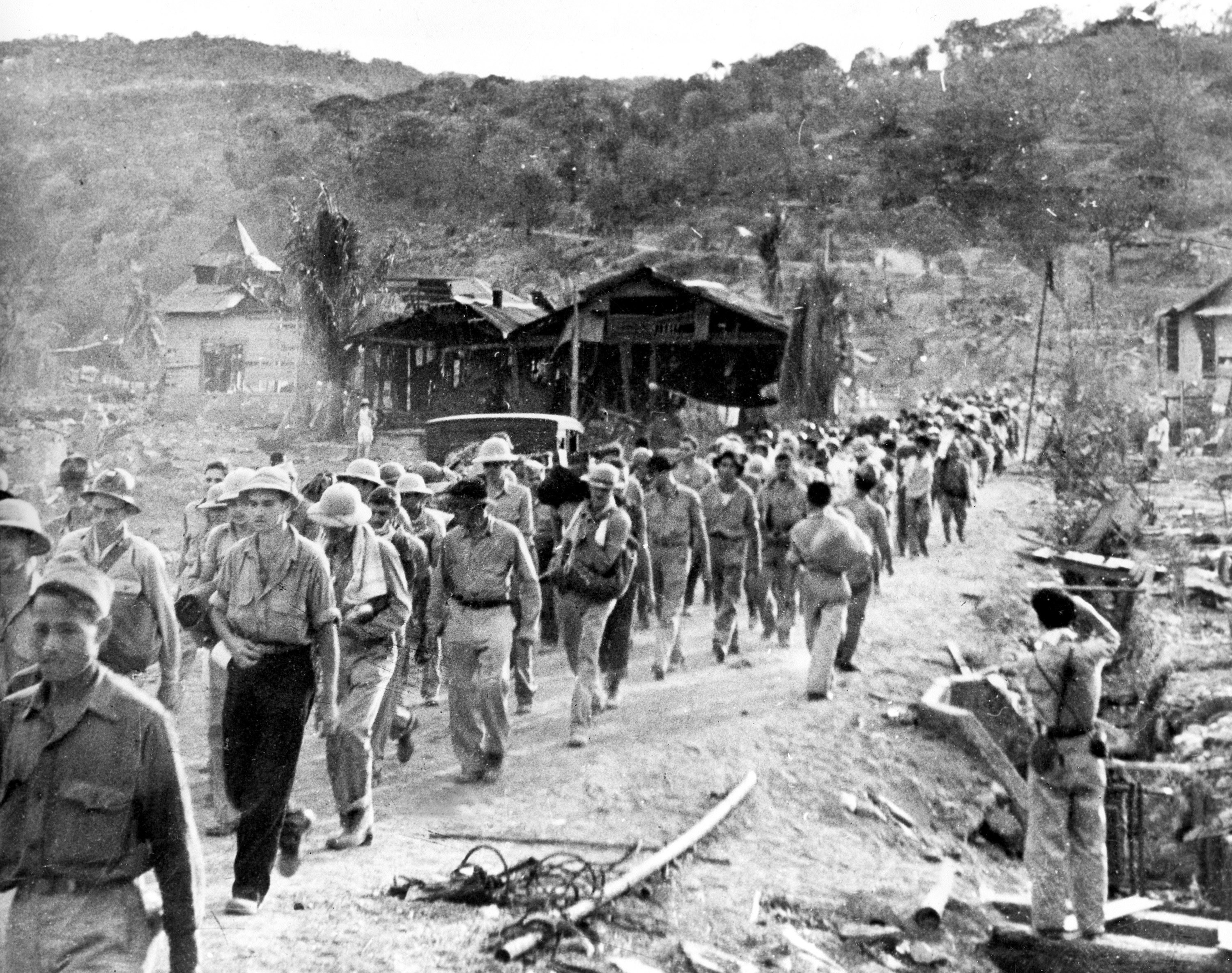

The American and Filipino forces that defended the Bataan Peninsula from January to April 1942 fought on desperately short rations. Within two months, Americans who had weighed 175 to 200 pounds had been reduced to walking skeletons of 135 to 145 pounds. Thousands contracted malaria and dysentery. Surrender on April 9, 1942, brought the exhausted American and Filipino troops no relief. Instead, the Japanese subjected their prisoners to the infamous Bataan Death March, forcing them to walk up to 140 miles without adequate food or water to a railroad station just off the peninsula. An estimated 10,650 POWs died on this hellish trek, many of them murdered when they could no longer stay on their feet or keep up with the others. Of the Death March victims, 650 were American.

On their arrival at Camp O’Donnell, most of the survivors plunged into despair. Reflecting on the horrors he witnessed at the POW enclosures in the Philippines, 1st Lt. Jack Hawkins of the 4th Marines wrote in his 1961 memoir Never Say Die, “There were many indeed who became so demoralized that they abandoned every tenet of personal integrity, honor, loyalty, and the accepted standards of human behavior. These sank to the level of animals or worse. There was a selfish, dog-eat-dog, every man for himself attitude among the prisoners and little group spirit. Discipline generally collapsed at the time of surrender. Many of the men would no longer obey the orders of their officers. Many of the officers, on the other hand, abandoned all responsibility to take care of the men. Military organizations fell apart, and were further broken up by the Japanese in a well-calculated effort to destroy group cohesion and convert the prisoners into an easily dominated, amorphous mass.”

Maj. Alva R. Fitch, an army artilleryman, described the dismal atmosphere that prevailed at Camp O’Donnell: “I have seen men try to go from barracks to the latrine who were too weak to walk and would fall down in the mud and rain, unable to rise—their friends, officers, or enlisted men, would sit in the barracks sheltered from the rain and look at them without moving to help them. I have seen men, not one but fifty or more at a time, lying in their own feces too weak to move and no one to move them.”

Col. J. V. Collier, a senior army staff officer at O’Donnell, also portrayed the camp as a place devoid of discipline and decency: “Food and water details were not supervised. Thirst crazed men were drinking the stream water. Food was not equally distributed to messes and it looked as tho the main officer’s mess was never the loser. Care of the sick was haphazard if at all. Men were found dead who had apparently died alone and unnoticed until the odor called attention to the decaying body.”

Some 17,600 Bataan survivors—1,600 of them American—perished at O’Donnell in the first seven weeks of captivity. But one group stood out through all of these hellish ordeals. Not one of the 650 Americans who died on the Death March was a member of the U.S. Marine Corps. Of the American POWs on the Philippines, U.S. Army POWs experienced a death rate of 42.6 percent for the entire war, while the marines had a death rate of 31.8 percent. For the Pacific theater as a whole, the marine POW death rate was half that of the army’s: 22.8 percent vs. 40.4 percent.

Some of these differences, to be sure, reflected lucky breaks. Marines taken prisoner in North China and Wake Island were mostly held in Shanghai, which had a healthy climate compared to the disease-ridden tropics.

Cosmopolitan Shanghai also had a large international settlement housing thousands of affluent Westerners who were willing to send the POWs cash, extra food, clothing, sports equipment, and a 3,000-volume library. Neutral Switzerland maintained a consulate general in the city, and its staff exerted tactful pressure on the Japanese to improve camp conditions. Shanghai was also one of only three urban centers behind Japanese lines where the International Committee of the Red Cross received permission to operate. Shanghai’s ICRC delegate, a Swiss national named Edouard Egle, sent the POWs extra food, clothing, and recreational gear. “If it had not been for the International Red Cross,” acknowledged Pfc. Floyd H. Comfort of the Wake Island marine garrison, “I guess we all would have starved to death.”

But even where soldiers and marines were held in identical conditions, the marines consistently fared better. As far as Lieutenant Hawkins could see, the only American contingent in the Philippine camps to resist sinking into this self-destructive anarchy was his own 4th Marines: “There was a way to inculcate in men the discipline, loyalty, spirit, mental stamina, and moral fortitude that were called for in the Japanese prison camps. It was the Marine Corps way. I was proud indeed to see that there was no collapse of discipline and group spirit among the marine prisoners. Standards of conduct among the marines were generally excellent, far superior to the norm.”

But even where soldiers and marines were held in identical conditions, the marines consistently fared better. As far as Lieutenant Hawkins could see, the only American contingent in the Philippine camps to resist sinking into this self-destructive anarchy was his own 4th Marines: “There was a way to inculcate in men the discipline, loyalty, spirit, mental stamina, and moral fortitude that were called for in the Japanese prison camps. It was the Marine Corps way. I was proud indeed to see that there was no collapse of discipline and group spirit among the marine prisoners. Standards of conduct among the marines were generally excellent, far superior to the norm.”

“The Marine Corps had a lot of discipline,” agreed Onnie Clem, a corporal in Hawkins’s regiment. “We followed orders and instructions from our officers. There wasn’t anybody who fussed with what the officers told them to do.”

It would be tempting to dismiss the claims of Hawkins and Clem as so much marine chest-thumping. But their testimony is borne out by many other anecdotal accounts—and the testimony of disinterested sources. Lt. Samuel C. Grashio, an army pursuit pilot who escaped with Hawkins from Davao Penal Colony in 1943, readily conceded, “As a group, the marines stood up better than most others under the burdens, humiliations, deprivations, and temptations of camp life.”

What happened at Cabanatuan, a large POW camp complex in the Philippines, was a striking illustration of marine determination. Cabanatuan was one of the most deplorable POW facilities in the Philippines, with an inmate population that had been decimated by more than two thousand deaths from June to October 1942. Deprived of leadership and inspiration, American soldiers turned on each other. The strong preyed on the weak, stealing the rations of those too sick to prevent it. Second Lt. Charles W. Burris, a fighter pilot with the U.S. Army Air Forces, witnessed unbelievable callousness at Cabanatuan: “That was one place where I learned that a human being is a marauder. You couldn’t keep food around because they’d steal it. They didn’t mind seeing a guy die. They just wanted his food. Everybody was concerned about themselves.”

In late October 1942, Lt. Col. Curtis Beecher of the 4th Marines was transferred to Cabanatuan No. 1. Beecher took one look at the overflowing latrines and the mud-choked paths linking the barracks and sprang into action. He organized clean-up, maintenance, and sanitary squads to install dry walkways, dig deeper drainage ditches, and increase the number of latrines.

It took a while, but Beecher’s efforts bore unmistakable fruit. Cabanatuan experienced its first day without a POW death on January 18, 1943. By February, the camp death rate had shrunk to ten men per month. On June 21, 1943, Capt. William H. Owen Jr. of the Army Coast Artillery pulled out his secret diary to praise Colonel Beecher and his marine staff for their “high sense of duty and long hours of work.”

Whenever the Japanese permitted them the slightest freedom of action, marine officers would assume control of the interior management of their camps, reestablishing order and directing their subordinates to work for group survival. At Shanghai War Prisoner Camp, the marines certainly benefited from the vastly superior treatment and climate enjoyed in that camp, but even there, the officers’ adamant insistence on maintaining discipline saved many lives within the ranks. Col. W. W. Ashurst of the North China marines ranked as the senior POW officer, but arthritis and a heart condition rendered the forty-eight-year-old Ashurst too sickly for active leadership. He had the good judgment to delegate much of his authority to his executive officer, Maj. Luther A. Brown.

Still fit and trim at forty-one, Brown possessed a dynamic personality and impeccable military bearing. “He always had on [a] polished Sam Brown belt, in full ‘Greens’ and shined shoes, neatly shaven and a well-trimmed ‘Ronald Coleman’ moustache,” marveled Pfc. Jack R. Williamson. Brown made it clear to both the North China and Wake marines that they still belonged to the Marine Corps, POWs or not. “We are a military organization,” he preached, “and I intend to see that we remain one. To do that, there must be discipline.” In the prewar Marine Corps, Brown was known as “Handbook” Brown for authoring The Marine’s Handbook, the enlisted man’s primary guide to service life. He was as tough as he was savvy. When one imprisoned leatherneck responded to a reprimand by snarling, “Goddamn the Marine Corps!” the major laid him out with a roundhouse punch to the face.

Brown demonstrated the same indomitableness in dealing with the Japanese. Among Brown’s most prized possessions was a U.S. Army training manual, The Rules for Land Warfare, which contained excerpts from the Geneva Convention on the proper treatment of POWs. Whenever his keepers violated the convention, Brown would march into the commandant’s office to file a forceful and authoritative protest. “He never quit trying to make life better for us,” remembered Cpl. Terence S. Kirk. “Every time I saw him heading for a conference with the Japs, he clutched his international law book like a preacher going to church with a bible.”

Brown never showed the Japanese the slightest hint of fear. When an enemy interpreter slapped him in the face in the presence of the camp commandant, the marine major promptly decked him. On another occasion, Brown disarmed a different interpreter who was drawing his samurai sword to behead Sir Mark Young, the British governor-general of Hong Kong. In another camp, such gestures would have earned Brown a summary execution, but authorities at Shanghai were either too impressed or intimidated by his courage to punish him.

Brown’s heroic exertions were supported by Maj. James Devereux, the commander of the Wake marines. “Hidden behind the routine, under the surface of life in prison camp was fought a war of wills for moral supremacy—an endless struggle, as bitter as it was unspoken, between the captors and the captives,” Devereux recounted. “The stake seemed to me simply this: the main objective of the whole Japanese prison program was to break our spirit, and on our side was a stubborn determination to keep our self-respect whatever else they took from us.”

A notorious martinet before the war, Devereux continued to insist on the strict observance of military courtesy within his captured detachment. “Our morale was good,” he declared, “so much different from some of these places I heard about, because I insisted on military courtesy. As a result of having the respect of the men, we could more properly represent them to the Japanese, and insist upon certain things we thought we were entitled to.” Devereux also did everything in his power to preserve his marines’ sense of group identity and loyalty. “This is a unit,” he would say. “This is the 1st Marine Defense Battalion, Wake Island Detachment. This is a group.” On another occasion, Devereux told his men, “I don’t need to threaten you. You’re still marines. Act like it.” Yearning for the day when Allied troops would liberate Shanghai and the Wake marines could reenter the war, Devereux had an enlisted clerk draw up a complete order of battle, assigning every officer and man to a specific battery and combat assignment.

Devereux did not hesitate to employ harsher means in his struggle to maintain order. When one of Devereux’s corporals started a fistfight with a sergeant, Devereux had the Japanese place the corporal in solitary confinement. He then assembled his marines and warned, “I will sacrifice a few of you to get the rest of you back.”

Another enlisted man remembered Devereux as saying that “he only wanted the good marines, the people that behaved like marines, and he was going to bring them back—even if he sacrificed the other half.” The major let it be known that he was keeping a list of insubordinate and disobedient men who would be court-martialed on their return home. Eventually, that list grew to a hundred names. The threat of court-martial turned out to be a bluff, but it gave Devereux an extra tool for preserving discipline and unit identity.

The two senior noncommissioned officers at Shanghai, Gunners Clarence B. McKinstry from Wake and William A. Lee from North China, judged and set punishments for POWs accused of minor offenses. McKinstry and Lee sentenced two inmates caught stealing to have their buttocks marked with the letter “T” in silver nitrate and paddled through camp. “The men were taken to each barracks,” related Pfc. Chester M. Biggs Jr., “where two swats were administered to each man’s buttocks with a large wooden paddle. This punishment was harsh but necessary, and it was effective. Theft nearly ceased.”

High recruiting standards, a luxury the Marine Corps could afford because of its relative smallness, provided marine drill instructors with young men who flourished under high training standards. In boot camp and afterwards, marine training stressed pride, aggressiveness, physical fitness, military bearing, personal hygiene, group sanitation, teamwork—and most important of all, the obligation to look out for one’s fellow marines. “Marines don’t surrender!” drill instructors would scream over and over. “Marines bring out their wounded! Marines don’t desert their buddies!”

During the Bataan Death March, long-service marines warned their juniors against drinking unsterilized water. Whenever the old hands came across water in the ruts and carabao wallows lining their route, they first purified it with iodine that they had secreted on their persons prior to the surrender. In prison camp, enlisted marines acted on their own initiative to establish “buddy systems,” which measurably improved their survival prospects. If a marine fell ill, sustained a serious injury, or pulled a stint in solitary confinement without food, his buddies often pooled small amounts of their own rations to sneak him double portions. These voluntary assessments kept up until the man in question was out of trouble. Several marines risked beatings and even death to steal food from the Japanese for ailing comrades.

Cpl. Henry L. Durrwachter, who was also captured on Wake Island, testified to the power of even the smallest supportive gesture in this entry from his secret diary: “Yesterday was my birthday and believe it or not I had a party. There wasn’t much to it as we only had bread and sugar to eat for cake. I thought it was swell of the fellows to remember. They gave me a couple of packs of cigarettes and a ring made out of a quarter. It made me feel fine to think I had friends like that.”

The Marine Corps has never been in the business of producing saints, and those of its sons captured in World War II knew moments of weakness and selfishness. Marine officers refused to dispense with certain nonessential privileges of rank, demanding exemption from heavy labor and orderlies to serve them. They had their food cooked separately, and many enlisted men were sure that their superiors received larger and more nutritious servings. The lower ranks argued among themselves over the distribution of their own food and other issues, many of them trivial. Sometimes these disagreements escalated from shouting matches to fistfights. When an NCO from Wake complained that he was losing control of some of the men in his barracks, Major Devereux barked, “You pick up a pick handle and use it, and don’t forget I said that, because you have to maintain discipline.”

These minor lapses prove that marines were human, but they do not diminish the moral triumph that the Marine Corps’ POWs won behind barbed wire. By sticking together and helping each other, they came home with their lives, their dignity, and an enduring sense of brotherhood. Cpl. Robert Brown spoke for more than just the Wake marines when he observed: “I don’t know of any other unit cohesion that works as well as this did. In the very bitterest days we had, this group got through by…one of the greatest cases of friendship the world has ever known.”