Many leading fighter pilots of World War II, such as Germany’s Erich Hartmann, Russia’s Ivan Kozhedub and America’s Richard Bong, looked as if they had been born for the honor. Japan’s ace of aces, Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, was a striking exception. One of his comrades in arms, Saburo Sakai, wrote that ‘one felt the man should be in a hospital bed. He was tall and lanky for a Japanese, nearly five feet eight inches in height. He had a gaunt look about him; he weighed only 140 pounds, and his ribs protruded sharply through his skin.’ Although Nishizawa was accomplished in both judo and sumo, Sakai noted that his comrade suffered almost constantly from malaria and tropical skin disease. He was pale most of the time.’

Sakai, who was one of Nishizawa’s few friends, described him as usually being coldly reserved and taciturn, ‘almost like a pensive outcast instead of a man who was in reality the object of veneration.’ To the select few who earned his trust, however, Nishizawa was intensely loyal.

Nishizawa underwent a remarkable metamorphosis in the cockpit of his Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter. “To all who flew with him,” wrote Sakai, “he became ‘the Devil’….Never have I seen a man with a fighter plane do what Nishizawa would do with his Zero. His aerobatics were all at once breathtaking, brilliant, totally unpredictable, impossible, and heart-stirring to witness.” He also had the hunter’s eye, capable of spotting enemy aircraft before his comrades knew there was anything else in the sky.

Even when a new generation of American aircraft was wresting the Pacific sky from the Japanese, many were convinced that as long as he was at the controls of his Zero, Nishizawa was invincible. And that proved to be the case.

Hiroyoshi Nishizawa was born on January 27, 1920, in a mountain village in the Nagano prefecture, the fifth son of Shuzoji and Miyoshi Nishizawa. Shuzoji was the manager of a sake brewery. After graduating from higher elementary school, Hiroyoshi worked for a time in a textile factory. Then, in June 1936, a poster caught his eye: an appeal for volunteers to join the Yokaren (flight reserve enlistee training program). He applied and qualified as a student pilot in Class Otsu No. 7 of the Japanese Navy Air Force (JNAF). He completed his flight training course in March 1939, graduating 16th out of a class of 71.

After service with the Oita, Omura and Sakura kokutais (air groups) in October 1941, Nishizawa was assigned to the Chitose Kokutai (Ku.). After the December 7, 1941, raid on Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of war with the United States, a chutai (squadron) from the Chitose group, including Petty Officer 1st Class (PO1C) Nishizawa, was detached to Vunakanau airfield on the newly taken island of New Britain, arriving in the last week of January 1942. They were equipped with 13 obsolescent Mitsubishi A5M fighters bequeathed to them by the Tainan and 3rd kokutais (which had re-equipped with the new A6M2 Zeros). The detachment got its first three Zeros on January 25.

Nishizawa was flying an A5M over Rabaul on February 3 when he and eight comrades encountered two Consolidated Catalina I flying boats of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) that were operating from the Allied sea and air base at Port Moresby, New Guinea. One of the Catalinas evaded the Japanese, but Nishizawa attacked the other and disabled one of its engines. The Australian pilot, Flight Lt. G.E. Hemsworth, managed to nurse his crippled plane back to Port Moresby on the remaining engine, while his gunner, Sergeant Douglas Dick, claimed an enemy fighter that was later counted as a probable. Nishizawa, on the other hand, was credited with the Catalina as his first victory.

Rabaul was attacked by small groups of Allied bombers throughout February. The Japanese took Sarumi and Gasmata in western New Britain on February 9 and promptly established staging bases there. On the following day, several detachments, including Nishizawa’s unit from the Chitose Ku., were amalgamated into a new air group, the 4th. As new Zeros became available, Nishizawa was assigned an A6M2 bearing the tail code F-108.

Twelve Zeros of the 4th Ku. were escorting eight bombers in a raid on Horn Island on March 14 when they encountered seven Curtiss P-40E Warhawks of the 7th Squadron, 49th Pursuit Group, U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF), led by Captain Robert L. Morissey. In the fight that ensued, three pilots of the 4th Ku., including Nishizawa, claimed six P-40s, along with two probables, while their opponents claimed five Zeros. In actuality, the Japanese lost two fighters and their pilots (Lt. j.g. Nobuhiro Iwasaki and PO1C Genkichi Oishi), while the Americans lost one P-40 whose pilot, 2nd Lt. Clarence Sandford, bailed out over Bremer Island.

The Japanese did not encourage the tallying of individual scores, being more inclined toward honoring a team effort by units. As with the French and Italians, Japanese victories were officially counted for the air group, not for individuals. Generally, attempts to verify personal claims by Japanese airmen can only be conducted from postwar examinations of their letters and diaries, or those of their comrades.

Nishizawa’s next claim was a Supermarine Spitfire over Port Moresby on March 24. He was also one of five Japanese pilots who participated in shooting down three alleged Spitfires claimed over the same location on March 28. It may safely be said, however, that the Japanese had misidentified their opponents, since there were no Spitfires in Australia at that time.

Meanwhile, on March 8, Japanese forces had landed in northeastern New Guinea and captured Lae and Salamaua. Then, on April 1, the JNAF underwent a reorganization, during which the 4th Ku. became exclusively a bombing unit, and its fighter chutai–including Nishizawa–was incorporated into the Tainan Ku., under the command of Captain Masahisa Saito. The unit operated from the jungle airstrip at Lae, where the living conditions were miserable. ‘The worst airfield I had ever seen, not excluding Rabaul or even the advanced fields in China,’ said Tainan Ku. member PO1C Saburo Sakai. But his wingman, PO3C Toshiaki Honda, gleefully described Lae as ‘the best hunting grounds on the earth.’ Honda was referring to Port Moresby, an Allied hornet’s nest lying just 180 miles away. There, RAAF P-40s were being bolstered by the Bell P-39 Airacobras of the 8th Pursuit Group, USAAF.

A flight of Tainan Ku. Zeros, led by Lt. j.g. Junichi Sasai, patrolled the Coral Sea and was making its return pass over Port Moresby on April 11 when the Japanese sighted a quartet of Airacobras. Sakai, covered by his two wingmen, PO3C Honda and Seaman 1st Class Keisaku Yonekawa, dove on the two rearmost P-39s and promptly shot down both.

‘I brought the Zero out of its skid and swung up in a tight turn,’ Sakai wrote, ‘prepared to come out directly behind the two head fighters. The battle was already over! Both P-39s were plunging crazily toward the earth, trailing bright flames and thick smoke….I recognized one of the Zeros still pulling out of its diving pass, Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, a rookie pilot at the controls. The second Zero, which had made a kill with a single firing pass, piloted by Toshio Ota, hauled around in a steep pullout to rejoin the formation.’

From that time on, Nishizawa and the 22-year-old PO1C Ota stood out among the veteran airmen of the Tainan Ku., later ranking alongside Sakai as the leading aces of the group. ‘Often we flew together,’ wrote Sakai, ‘and were known to the other pilots as the ‘cleanup trio.” Ota shared Nishizawa’s mastery of the Zero’s controls, but his personality could not have been more different; he was outgoing, jocular and amiable. Sakai thought Ota would have been ‘more at home, I am sure, in a nightclub than in the forsaken loneliness of Lae.’

For the next several weeks, the Tainan Ku. had its share of successes, but opportunities seemed to elude Nishizawa. On April 23, he, Sakai and Ota shot up Kairuku airfield north of Port Moresby, and on April 29, Nishizawa was one of six Zero pilots who celebrated Emperor Hirohito’s birthday by strafing Port Moresby Field itself. On neither occasion, however, did the Japanese encounter aerial opposition. Then, on May 1, eight Zeros were heading for Port Moresby when they encountered 13 P-39s and P-40s flying along slowly at 18,000 feet. Nishizawa, as usual, spotted them first and swung around in a wide turn to attack the enemy planes from the left and rear. His seven comrades were not far behind, and they took the Americans completely by surprise, shooting down eight before the survivors dove away.

Sakai, who claimed two victories in the fight, described what happened when they returned to Lae: ‘Nishizawa leaped from his cockpit as the Zero came to a stop. We were startled; usually he climbed down slowly. Today, however, he stretched luxuriously, raised both arms above his head, and shrieked, ‘Yeeeeooow!’ We stared in stupefaction; this was completely out of character. Then, Nishizawa grinned and walked away. His smiling mechanic told us why. He stood before the fighter and held up three fingers. Nishizawa was back in form!’

Nishizawa remained in form, downing two P-40s over Port Moresby the next day and another P-40 on May 3. On May 7, Sakai, Nishizawa, Ota and PO1C Toraichi Takatsuka jumped 10 P-40s over Port Moresby, each pilot accounting for a Curtiss on his first pass. Four more P-40s turned on them, but the Japanese outmaneuvered them with tight, arcing loops. They came around behind their attackers and shot down another three. Nishizawa shared in the destruction of two P-39s on May 12, and got two more Airacobras on May 13.

Torrential rains grounded the Tainan Ku. on May 15, and on the following dawn a flight of North American B-25 Mitchell bombers of the 3rd Bomb Group swooped over Lae and cratered the runway with bomb hits. The day was spent repairing the damage. That night, Nishizawa, Ota and Sakai were lounging in the radio room, listening to the music hour on an Australian station when Nishizawa recognized Camille Saint-Saëns’ eerie ‘Danse Macabre.’ ‘That gives me an idea,’ he said excitedly. ‘You know the mission tomorrow, strafing at Moresby? Why don’t we throw a little dance of death of our own?’

Ota dismissed Nishizawa’s proposal as the ravings of a madman, but he persisted. ‘After we start home, let’s slip back to Moresby, the three of us, and do a few demonstration loops right over the field,’ Nishizawa suggested. ‘It should drive them crazy on the ground!’

‘It might be fun,’ replied Ota. ‘But what about the commander? He’d never let us go through with it.’

‘So?’ replied Nishizawa with a broad grin. ‘Who says he must know about it?’

On May 17, Lt. Cmdr. Tadashi Nakajima led the Tainan Ku. in a maximum effort to neutralize Port Moresby, with Sakai and Nishizawa as his wingmen. The strafing run accomplished nothing, however, and three formations of Allied fighters took on the Zeros in a swirling dogfight. Five P-39s were claimed by the Japanese, including a double for Sakai and some possible shared victories for Nishizawa. However, two Zeros were shot up over the field and later crashed in the Owen Stanley Mountains, killing Lt. j.g. Kaoru Yamaguchi and PO2C Tsutomu Ito.

The Japanese formation realigned for the return flight. Sakai signaled Nakajima that he was going after an enemy plane he had seen and peeled off. Minutes later, he was over Port Moresby again, to keep his rendezvous with Nishizawa and Ota. After establishing their routine by means of hand gestures and checking one more time for Allied fighters, the trio performed three tight loops in close formation. After that, a jubilant Nishizawa indicated that he wanted to repeat the performance. Diving to 6,000 feet, the Zeros did three more loops, still without coming under any fire from the ground. The Japanese then headed back to Lae, arriving 20 minutes after the rest of the unit had landed.

At about 9 p.m., an orderly told Sakai, Ota and Nishizawa that Lieutenant Sasai wanted them in his office immediately. When they arrived, he held up a letter. ‘Do you know where I got this thing?’ he shouted. ‘No? I’ll tell you, you fools; it was dropped on this base a few minutes ago, by an enemy intruder!’

The letter, written in English, said: ‘To the Lae Commander: We were much impressed with those three pilots who visited us today, and we all liked the loops they flew over our field. It was quite an exhibition. We would appreciate it if the same pilots returned here once again, each wearing a green muffler around his neck. We’re sorry we could not give them better attention on their last trip, but we will see to it that the next time they will receive an all-out welcome from us.’

Nishizawa, Sakai and Ota stood at stiff attention and made a herculean effort to conceal their mirth while Sasai dressed them down over their ‘idiotic behavior’ and prohibited them from staging any more aerobatic shows over enemy airfields. Still, the Tainan Ku.‘s three leading aces secretly agreed that Nishizawa’s aerial choreography of the ‘Danse Macabre’ had been worth it.

Nishizawa added another P-39 to his score on May 20. A strike on Lae by six B-25Cs of the 13th Squadron, 3rd Bomb Group, on May 24 brought a vicious reaction by 11 Zeros. Nishizawa reached the Mitchells first, and in moments his cannon shells sent the lead plane, flown by Captain Herman F. Lowery, crashing in flames just beyond the Japanese airstrip. In the running fight that ensued between Lae and Salamaua, Ota got the second B-25 in the formation, Sakai got two and Sasai another, leaving only one riddled survivor to return to Port Moresby.

The Japanese were flying low over the jungle on May 27 when they encountered four Boeing B-17Es of the 19th Bomb Group flying in column, escorted by 20 Bell P-400s (export models of the P-39 with a 20mm cannon in place of the P-39’s 37mm weapon) of the 35th Pursuit Group, which had arrived at Port Moresby to relieve the battered 8th Group in late May. The Zeros attacked from below and a low-level dogfight ensued, during which Sakai shot down one Airacobra and drove another down to crash in a mountain pass. Coincidentally, Nishizawa and Ota also claimed Airacobras under identical circumstances, each one driving his victim down to crash and then pulling up at the last possible second.

Nishizawa added another P-39 to his personal tally on June 1, followed by two more on June 16. On June 25, he personally downed a P-39 and shared in the destruction of a second with two other pilots. Another P-39 fell to his guns on July 4.

Despite such dazzling successes, the Japanese did not have things entirely their way. Twenty-three Zeros intercepted a flight of B-26s over Lae on June 9. They had claimed four of them over Cape Ward Hunt when they were jumped by 11 P-400s of the 39th Squadron, 35th Fighter Group. Warrant Officer Satoshi Yoshino, a 15-victory ace, was shot down and killed by Captain Curran L. Jones, who later brought his score up to five while flying a Lockheed P-38F Lightning. Even the redoubtable Nishizawa met his match on July 11; his Zero was shot up in an unsuccessful attempt to bring down a B-17, but he did down a P-39 on the same day. Similarly, a Lockheed A-28 Hudson proved too fast and tough for him to bring down on July 22. On July 25, however, he downed another P-39 over Port Moresby and joined eight other Zeros in shooting down a B-17 over Buna.

When five more B-17s came to bomb Lae on August 2, the Japanese tried out a new tactic–attacking head-on. The result was spectacular–Nishizawa’s cannon shells tore into the first and it exploded in flames. Ota, Sasai and Sakai, also accounted for B-17s. Three P-39s tried to intervene, only to be outmaneuvered and shot down by Nishizawa, Ota and Sakai. After a running fight, the fifth Fortress was also shot down, but not before its gunners had damaged Sakai’s Zero and shot down Seaman 1st Class Yoshio Motoyoshi—Nishizawa’s wingman. Upon landing, Nishizawa ignored the cheers of his ground crewmen. ‘Refuel my plane and load my guns,’ he ordered, and he set out on a lone search for his lost wingman. ‘Two hours later he returned,’ Sakai wrote, ‘misery written on his face.’

The Tainan Ku. moved to Lakunai airfield on Rabaul the next day. On August 7, word arrived that U.S. Marines had landed on the island of Guadalcanal, more than 500 miles away at the lower end of the Solomon Islands chain, at 5:20 that morning. Without delay, Lt. Cmdr. Nakajima led 17 Zeros to escort 27 Mitsubishi G4M bombers of the 4th Ku. in an attack on the U.S. Navy task force supporting the invasion. The Japanese were met by 18 Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat fighters and 16 Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless dive bombers from the aircraft carriers Saratoga, Enterprise and Wasp.

Nishizawa was credited with six F4Fs in this first air battle between land-based Zeros and American carrier fighters. One of his victims was probably Lieutenant Herbert S. (‘Pete’) Brown of VF-5, who was attacked by a Zero that made a full-deflection shot from about 1,500 feet overhead, shattering his canopy and wounding him in the hip and leg. Pete Brown reported that his opponent came alongside him, and after the two adversaries had looked each other over, the Japanese pilot grinned and waved. The skill and wildness of Brown’s antagonist both suggest Nishizawa’s style, but for neither the first nor last time, his assumption of the F4F’s demise was premature. Brown managed to make it back to his carrier, Saratoga. Other likely VF-5 victims of Nishizawa included Ensign Joseph R. Daly, who was shot down in flames and badly burned but parachuted to safety just off Guadalcanal, and Lt. j.g. William M. Holt, who was killed.

After a difficult fight, Sakai destroyed an F4F of VF-5 flown by Lieutenant James J. Southerland II, who was wounded but bailed out and survived. Sakai then downed an SBD-3 of Wasp‘s scouting squadron VS-71, killing Aviation Radioman 3rd Class Harry E. Elliott and wounding the pilot, Lieutenant Dudley H. Adams, who was subsequently rescued by the destroyer Dewey. Next, Sakai pounced on what looked like eight Wildcats–only to discover too late that they were really SBDs of VB-6 and VS-5. One of the dive bombers’ .30-caliber rear guns struck Sakai in the head, temporarily blinding him.

The fight broke up and the Zeros re-formed for the return leg of their long mission. Nishizawa noticed that Sakai was missing and went into another of his mad rages. Peeling off on his own, he searched the area, both for signs of Sakai and for more Americans to fight, presumably even if he had to ram them. Eventually, he cooled off and returned to Lakunai. Later, to everyone’s amazement, the seriously wounded Sakai arrived, after an epic 560-mile flight. Nishizawa personally drove him, as quickly but as gently as possible, to the surgeon. Evacuated to Japan on August 12, Sakai lost an eye, but returned to combat in 1944 and brought his final score up to 64–the fourth-ranking Japanese ace.

Japanese claims in the August 7 air battle totaled 36 F4Fs (including seven unconfirmed) and seven SBDs. Actual American losses came to nine Wildcats and a Dauntless. Four F4F pilots (Holt, Lt. j.g. Charles A. Tabberer and Ensign Robert L. Price of VF-5, and Aviation Pilot 1st Class William J. Stephenson of VF-6) and SBD radioman Elliott were killed. American claims were more modest–seven bombers, plus five probables, and two Zeros. The Japanese actually suffered the loss of four G4Ms and another six returning to base so damaged as to be written off, along with the loss of two Tainan Ku. members, PO1C Mototsuna Yoshida (12 victories) and PO2C Kunimatsu Nishiura, both killed by Lt. j.g. Gordon E. Firebaugh of Enterprise‘s VF-6, just before Firebaugh himself was shot down and forced to bail out.

Sakai and Yoshida were just the first of many Japanese aces whose careers would be cut short in the course of a six-month struggle with the U.S. Army, Navy and Marine squadrons that were operating from Guadalcanal’s Henderson Field. Junichi Sasai, whose official score then stood at 27, was killed by Captain Marion E. Carl of Marine fighter squadron VMF-223 on August 26. On September 13, PO3C Kazushi Uto (19 victories), Warrant Officer Toraichi Takatsuka (16) and PO2C Susumu Matsuki (8) were killed in a wild dogfight with F4F-4s of VF-5 and VMF-223.

Nishizawa survived and adapted to the improving American aircraft and tactics. On October 5, he and eight other pilots downed a B-25 attacking Rabaul, and on the 8th he and eight comrades accounted for a torpedo bomber over Buka. During an encounter over Guadalcanal between 16 Tainan Ku. Zeros and eight F4F-4s of VMF-121 on October 11, Nishizawa scored the only success for either side when he forced 2nd Lt. Arthur N. Nehf to ditch his Wildcat in Lunga Channel. Nishizawa was credited with one of five F4Fs claimed by the Tainan Ku. during a fight with VMF-121 over Guadalcanal on October 13. The only actual Marine loss occurred when PO1C Kozaburo Yasui, PO3C Nobutaka Yanami and Seaman 1st Class Tadashi Yoneda shot up a Wildcat whose pilot, Captain Joseph J. Foss of VMF-121, succeeded in making a forced landing on Henderson Field. Nishizawa claimed another F4F on the 17th, along with a torpedo bomber shared with another pilot. He claimed an F4F in a melee with Major Leonard K. Davis’ VMF-121 on October 20, but in fact neither side suffered any losses.

Toshio Ota mortally wounded Marine gunner Henry B. Hamilton of VMF-212 on October 21, for his 34th victory, but was himself shot down and killed moments later by 1st Lt. Frank C. Drury. On October 25, the career of another Tainan Ku. ace ended when Seaman 1st Class Keisaku Yoshimura (9 victories) fell victim to Joe Foss of VMF-121.

The JNAF underwent another reorganization on November 1, in which all units bearing names were redesignated by number. The Tainan Ku. thus became the 251st Kokutai. In the middle of the month, the group was recalled to Toyohashi air base in Japan to replace its losses. Commander Yasuna Kozono became the new commanding officer, Lt. Cmdr. Nakajima became its air officer, and new personnel were trained by a cadre of 10 surviving veterans, including Nishizawa. By the time he was withdrawn to Toyohashi, Nishizawa’s total of personal and shared victories stood at about 55, but the tide of battle was turning in favor of the Americans. The last Japanese troops were evacuated from Guadalcanal on February 7, 1943. From that time on, the Allies would be permanently on the offensive in the Pacific.

While in Japan, Nishizawa visited Sakai, who was still recuperating in the Yokosuka hospital. Updating his friend on events, Nishizawa complained of his new duty as an instructor: ‘Saburo, can you picture me running around in a rickety old biplane, teaching some fool youngster how to bank and turn, and how to keep his pants dry?’ Nishizawa also described the loss of most of their comrades to the growing might of the American forces. ‘It’s not as you remember, Saburo,’ he said. ‘There was nothing I could do. There were just too many enemy planes, just too many.’ Even so, Nishizawa could not wait to return to combat. ‘I want a fighter under my hands again,’ he said. ‘I simply have to get back into action. Staying home in Japan is killing me.’

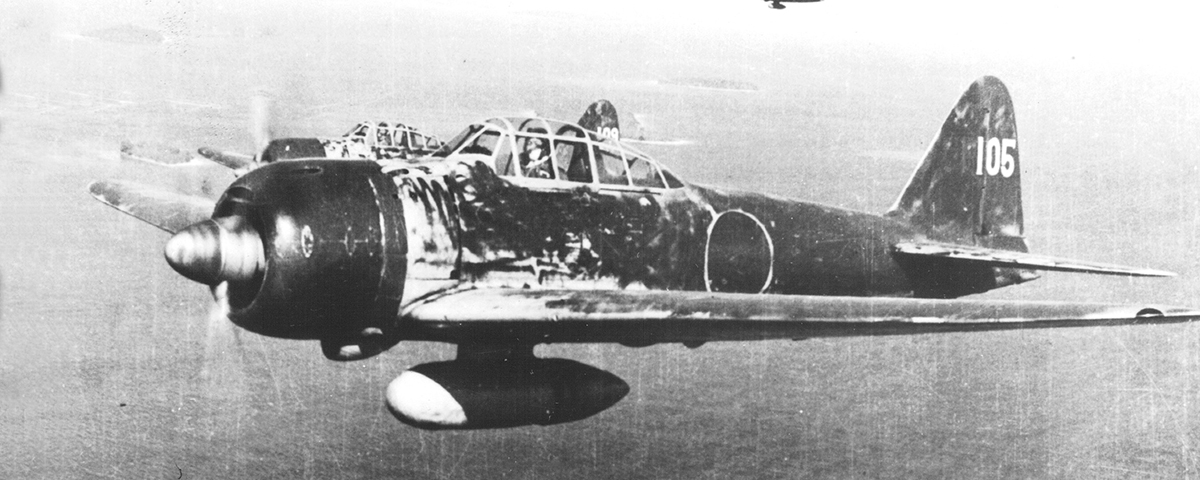

The 251st Ku. returned to Rabaul on May 7, 1943, and resumed operations over New Guinea and the Solomons. Among the Zeros known to have been flown by Nishizawa during that time was an A6M3 Type 22 with the tail code UI-105. On May 14, 32 Zeros of the 251st Ku. escorted 18 G4M bombers of the 751st Ku. on a large raid to Oro Bay, New Guinea. They were met by P-40s and new Lockheed P-38 Lightnings of the 49th Fighter Group. A confused dogfight took place, during which the Japanese claimed 13 Americans (five of them admitted to be probables), while the 49th Group claimed 11 G4M ‘Bettys’ (Allied code term for the bombers) and 10 of their ‘Zeke’ escorts. The actual result was that six G4Ms failed to return to their base at Kavieng, New Ireland, and four returned damaged, while the 251st Ku. lost no pilots at all.

The only American loss was 2nd Lt. Arthur Bauhoff, whose P-38 was downed by two A6M3s, one of which was flown by Nishizawa. Bauhoff was seen parachuting into the water, but the boat that was sent to rescue him found only a pack of frenzied sharks to hint at his fate. The 7th Squadron’s P-40Ks attacked the bombers, but 1st Lt. Sheldon Brinson was thwarted by a wildly maneuvering Zeke whose pilot was clearly an old veteran, and he escaped only by diving away. That may have been the P-40 claimed that day by Nishizawa, whose fighting style was certainly consistent with Brinson’s description. Another P-40K of the 7th was so shot up that its landing gear collapsed, and the plane was written off, although its pilot, 1st Lt. John Griffith, was unhurt.

The 251st and 204th kokutais took off on June 7 to sweep the Guadalcanal area, only to be intercepted over the Russell Islands by a mixed bag of Allied opposition–Marine F4F-4s and Chance Vought F4U-1 Corsairs of VMF-112; P-40Fs of the 44th Squadron, 18th Fighter Group; P-38Fs of the 339th Squadron, 347th Fighter Group; and P-40E Kittyhawks of No. 15 Squadron, Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF). As on May 14, both sides overclaimed–the 251st Ku. alone claiming 23 victories (five of which were probables), while the Allies claimed a total of 24 Zeros. Actual Allied losses were four F4Us and a P-40, along with several damaged (two of the four damaged RNZAF Kittyhawks had to crash-land on Russell Island), but miraculously, all their pilots survived. On the other hand, of the eight Zeros that were destroyed, seven of their pilots were killed, including four from the 251st Ku. Nishizawa’s claims included his first Corsair, which may have been that of VMF-112’s commander, Major Robert B. Fraser, who, after downing two Zeros for his fifth and sixth victories, was shot down himself but bailed out safely.

The main drama of the day, however, centered on PO1C Masuaki Endo, who shot up a P-38 before being driven off its tail by P-40 pilot 1st Lt. Jack A. Bade of the 44th Squadron, and was later credited with the Lightning by Japanese eyewitnesses. Endo then got into a head-on gun duel with 1st Lt. Henry E. Matson of the 44th, but his Zero was set on fire by the American’s six .50-caliber machine guns. In a final self-sacrificial act, Endo crashed his Zero into Matson’s P-40. Matson bailed out and survived the attention of three approaching Zeros by giving them a toothy grin and waving at them, to which the Japanese responded by waving back and flying away. He was subsequently recovered by a rescue boat. Matson’s P-40 was credited as the 14th victory for Endo, whose death deprived the JNAF of yet another invaluable, experienced fighter pilot.

By mid-June, Nishizawa had added six more Allied planes to his total. After that, Japanese naval air groups completely abandoned the practice of recording personal victories, and Nishizawa’s exact record became difficult to ascertain. During that time, however, his achievements were honored by a gift from the commander of the 11th Air Fleet, Vice Adm. Jinichi Kusaka–a military sword inscribed Buko Batsugun (‘For Conspicuous Military Valor’).

Nishizawa was transferred to the 253rd Ku. in September. He operated from Tobera, New Britain, until he was recalled to Japan a month later. At that time, Lt. Cmdr. Harutoshi Okamoto, commander of the 253rd Ku., reported that Nishizawa’s total score stood at 85.

Nishizawa was promoted to warrant officer in November and again served as a trainer in the Oita Ku., but his performance in that role was judged barely tolerable by his superiors. He was assigned to the 201st Ku. in February 1944, transferring from Atsugi to defend the northern Kurile Islands against bombing raids by the U.S. Eleventh Air Force. Few opportunities to engage the enemy arose, however, and Nishizawa did not add anything to his score.

The threat of an American invasion of the Philippines grew, and 29 aircraft of Hikotai (detachment) 304 of the 201st Ku. were dispatched to Bamban airfield on the island of Luzon on October 22, 1944. On October 24, Nishizawa was with a contingent from that detachment, which was sent to Mabalacat airfield on Cebu Island.

On the following day, Nishizawa led three A6M5s, flown by Misao Sugawa, Shingo Honda and Ryoji Baba, to provide escort for five others, carrying 550-pound bombs. The volunteers piloting the bomb-armed Zeros, led by Lieutenant Yukio Seki, were to deliberately crash their planes into the American warships they encountered, preferably aircraft carriers, in the first official mission of the suicidal kamikaze, or ‘divine wind.’ Brushing aside interference from 20 Grumman F6F Hellcats, Nishizawa and his escorts claimed two of the Americans, bringing his personal score up to 87. The suicide attack was also successful–four of the five kamikazes struck their targets and sank the escort carrier St. Lô.

Nishizawa reported the sortie’s success to Commander Nakajima after returning to base and then volunteered to take part in the next day’s kamikaze mission. ‘It was strange,’ Nakajima later told Saburo Sakai, ‘but Nishizawa insisted that he had a premonition. He felt he would live no longer than a few days. I wouldn’t let him go. A pilot of such brilliance was of more value to his country behind the controls of a fighter plane than diving into a carrier, as he begged to be permitted to do.’ Instead, Nishizawa’s plane was armed with a 550-pound bomb and flown by Naval Air Pilot 1st Class Tomisaku Katsumata, a less experienced pilot who nevertheless dove into the escort carrier Suwannee off Surigao. Although the ship was not sunk, she burned for several hours–85 of her crewmen were killed, 58 were missing and 102 wounded.

Meanwhile, Nishizawa and several other pilots left Mabalacat that morning aboard a bomber to pick up some replacement Zeros at Clark Field on Luzon. Over Calapan on Mindoro Island, the bomber transport was attacked by two Hellcats of VF-14 from the carrier Wasp and was shot down in flames. Nishizawa, who had believed that he could never be shot down in aerial combat, died a helpless passenger–probably the victim of Lt. j.g. Harold P. Newell, who was credited with a ‘Helen’ (Allied code name for the Nakajima Ki.49 Donryu army bomber) northeast of Mindoro that morning.

Upon learning of Nishizawa’s death, the commander of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, honored him with a mention in an all-units bulletin and posthumously promoted him to the rank of lieutenant junior grade. Because of the confusion toward the end of the war, the publication of the bulletin was delayed and funeral services for Japan’s greatest fighter pilot were not held until December 2, 1947. Nishizawa was also given the posthumous name Bukai-in Kohan Giko Kyoshi, a Zen Buddhist phrase that translates: ‘In the ocean of the military, reflective of all distinguished pilots, an honored Buddhist person.’

It was not a bad epitaph for a man once known as the Devil.

This article was written by Jon Guttman and originally published in the July 1998 issue of Aviation History. For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!