Charles Young was born into slavery in a two-room log cabin in Mays Lick, Kentucky, on March 12, 1864. His father Gabriel later fled to freedom and in 1865 enlisted as a private in the 5th Regiment, U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery. His father’s enhanced status as a “Grand Army man” impressed Charles as he grew up in Ripley, Ohio. The son was sent to an all-black elementary school, but he was able to attend Ripley’s integrated high school and graduated at the top of his class in 1881. Two years later, at the urging of his father, he took the West Point entrance examination. Twenty-year-old Young scored well, received the required nomination from Ohio’s 12th District Congressman Alphonso Hart and reported to the U.S. Military Academy in June 1884. He was the ninth black American admitted to West Point; he would be the third to graduate with a commission as a second lieutenant.

Young had a miserable time at West Point. Charles Rhodes, a white cadet in Young’s class, remembered him as “a rather awkward, overgrown lad, large-boned and robust in physique, and of a nervous, impulsive temperament.” Rhodes recalled that Young’s “life was lonesome” at West Point–hardly a surprise, as most white cadets refused to associate with blacks and subjected them to racial slurs, cruel slights and hostile treatment beyond the normal hazing.

Young considered quitting West Point after his first year, but his father convinced him to stay—though it took Young five years to complete the curriculum. He had difficulty with engineering but excelled in languages, gaining a working knowledge of Latin, Greek, French, Spanish and German. His decision to persevere was a source of pride for him, and he accepted that “duty, honor, country” must be the foundation of his life as an officer. But Young later advised a young black man interested in attending West Point that he could expect “a dog’s life there.”

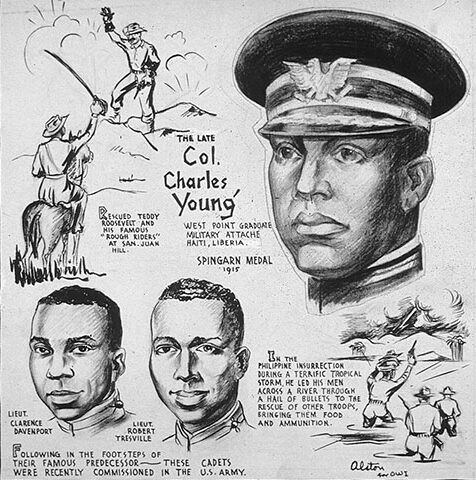

Young graduated last in his 49-member class in 1889, and from 1894 until 1936 he was the lone black West Point graduate in the Army.

Assigned to the predominantly black 9th U.S. Cavalry (aka “buffalo soldiers”), Young served in Nebraska and Utah in the early 1890s before reporting to Wilberforce University, near Dayton, Ohio, as professor of military science and tactics. While at Wilberforce, Young befriended W.E.B. Du Bois, a classics professor who would become one of the leading black American intellectuals of the early 20th century. After leaving Wilberforce, Du Bois and Young continued to correspond, and Du Bois considered Young one of the “talented tenth”—those individuals whom Du Bois and other prominent black intellectuals believed would lead the struggle for racial justice in America.

Young’s patience, discipline and hard work paid off when the United States declared war on Spain in April 1898. On May 13 of that year Ohio Governor Asa S. Bushnell appointed 1st Lt. Young a brevet major in command of the 9th Battalion Ohio Volunteers, an all-black unit. While the major and his men remained stateside, Young gained valuable command experience.

At war’s end Young returned briefly to Wilberforce University before rejoining the 9th Cavalry at Fort Duchesne, Utah. While in command of I Troop, 1st Lt. Young (he had reverted to his permanent rank) learned that one of his men, Sgt. Maj. Benjamin O. Davis, wanted to apply for a commission. Young tutored Davis for the competitive examination and wrote a glowing letter of recommendation. In early 1901 Davis passed the test and was commissioned a second lieutenant. He never forgot Young’s help, particularly after becoming the first black American to reach the rank of general.

In February 1901 Young was promoted to captain in the Regular Army—another first for a black man. Two months later Young and I Troop sailed for the Philippines with the rest of the 9th Cavalry. Stationed on Samar, Young and his men fought the Filipino insurrectos in the jungles of the island’s rugged interior. During one operation Young was leading a scouting party when it came under attack. “Captain Young had fired his revolver so fast,” a corporal later recalled, “that the sight was blown off.” Young then took another officer’s pistol and kept firing at the enemy until reinforcements arrived. Such instances of combat leadership earned Young the moniker “Follow Me” from his men, who vowed they would give their lives for him. The 9th Cavalry returned stateside in late 1902.

In May 1903, 39-year-old Captain Young, three other officers and 93 enlisted soldiers left the Presidio of San Francisco for Sequoia and General Grant national parks in north-central California. In the years before the 1916 creation of the National Park Service, the Army ran America’s national parks. The War Department detailed junior officers to the Department of the Interior to serve as acting superintendents during the summer. These assignments were always short-lived; the officers never served for more than two consecutive seasons. Consequently, little was expected.

But Young threw himself into his new job. He took charge of the payroll accounts and directed the activities of the park rangers. He stopped the illegal grazing of sheep in the park’s meadows. Young had his men dig firebreaks and place fences around the giant sequoias to protect them from root damage. The men also began work on a major project: completing a road to the Giant Forest, the park’s major attraction. Civilian crews had completed two-thirds of the road during the past few seasons. Young and his troopers finished it in two months and added another two miles to the road, going on to complete an unfinished road to the town of Visalia, seven miles farther west.

Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock was enormously impressed with Young’s work. Visalia town leaders also heralded Young’s “energy and enthusiasm” and gave him a unanimous vote of thanks. The National Park Service remains proud of Young, devoting a number of website pages to him and his achievements as the first black superintendent of a national park. At the completion of his assignment in the park, Young returned to San Francisco. There he married Ada Mills, the daughter of a prosperous mulatto family from Oakland. His new bride accompanied Young on his next tour of duty, as military attaché to Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Young and his wife arrived in Port-au-Prince in late May 1904. He threw himself into his new assignment and over the next two years made exploratory horseback trips throughout Hispaniola. He wrote topographical reports and drew maps, compiled a French-English-Creole dictionary and wrote a 273-page monograph on Haiti’s government, law and culture. He analyzed the military preparedness of both island nations and reported on their fortifications. When Young left Port-au-Prince in April 1907, William P. Powell, the American minister in Haiti, wrote to Secretary of State Elihu Root that Young should be commended for his “careful and painstaking work.” In 1907 and 1908 Young served in Washington, D.C., in the War Department’s military intelligence section, where he spent much of the year relating his experiences in Haiti to both senior Army leaders and State Department officials.

Young then redeployed to the Philippines on a one-year assignment as commander of 3rd Squadron, 9th Cavalry. His wife, Ada, and their 2-year old son came along. Their presence was a source of joy to Young, as he was the lone black American officer in the Philippines and still faced prejudice in a white man’s Army. Unlike his first tour in the Philippines, during which he had seen considerable combat, his second tour was routine and uneventful, aside from the birth of a daughter.

Returning to the United States in May 1909, Young reported to Fort D.A. Russell, Wyoming, then the largest cavalry post in the United States, where he took command of 2nd Squadron, 9th Cavalry. Two years later, he again made history when the War Department selected him to be the first military attaché to the Republic of Liberia.

Arriving in Monrovia with Ada in May 1912, Young began reorganizing the nascent Liberian Frontier Force and constabulary. Soon promoted to major, he saw combat in December 1912 when hostile tribesmen ambushed the Liberian troops he was accompanying. Over the next few days Young and the Liberian unit fought from town to town, and Young suffered a gunshot wound to his arm––the only time in his career he was wounded in action.

In early 1913 Young contracted malarial blackwater fever and became so debilitated he could scarcely walk. Returning to the United States for treatment, he nearly died on the voyage home. He spent months recovering at home in Ohio, then returned to Liberia to complete his assignment, which he did in November 1915.

Back on U.S. soil Young discovered he had achieved renown in the black community. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People awarded him the Spingarn Medal in 1916, an annual award for outstanding achievement by a black American. (General Colin Powell is the only other career soldier to have earned the medal, in 1991.) In March 1916, Major Young took command of 2nd Squadron, 10th Cavalry, at Fort Huachuca, Arizona—just in time to participate in the Army’s Punitive Expedition into Mexico. Mexican guerrilla leader Pancho Villa and his men had raided the Army’s garrison at Columbus, New Mexico, killing or wounding more than two-dozen soldiers and civilians, and Young and his troopers joined Brig. Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing’s campaign in search of Villa.

Young and his men ran into a large contingent of Villa’s troops at a ranch in Mexico on March 31, 1916. Determined to rout the guerrillas from their defensive position behind stone walls, Young led his mounted troopers in a whooping, shouting charge that so unnerved the defenders that they broke and ran. Two weeks later Young and the 10th Cavalry rescued embattled troopers from the 13th Cavalry who had been cornered by Mexican government troops and were fighting for their lives. The Mexicans had already killed or wounded a number of Americans, and their commander, Major Frank Tompkins, was reportedly so thrilled to see the reinforcements, he cried out, “By God, Young, I could kiss every one of you!” Quipped Young, who was riding at the head of the troops, “Hello, Tompkins! You can start in on me right now.”

In early 1917 it was clear to many observers that America’s entry into World War I was imminent, and Young believed he was ready for war in France. So did Pershing; he sent a list to the War Department of those officers whose performance in the Punitive Expedition made them deserving of brigade command. Lt. Col. Young (he had been promoted in June 1916) was on that list. When the United States declared war on the Central Powers in April 1917, many in the black community expected that the 53-year-old Young would play an important role, reach flag rank and make history as America’s first black general.

It was not to be. While stationed at Fort Huachuca in May 1917, Young had passed the examination for promotion to colonel, but his medical examination found high blood pressure and albuminuria, suggesting kidney damage. Two medical boards recommended that his physical condition be waived and that he be promoted and kept on active duty, but the chief medical officer disagreed. Despite many letters written on his behalf, an intensive lobbying effort by the NAACP and his own pleas to the War Department, Young was forced to retire as a colonel in July 1917.

While Young was the first black American to reach that rank, the promotion was meaningless to him, as his military career seemed over. The medical examination was correct—Young’s kidneys were severely damaged—but the color of his skin may have also factored into his forced retirement: A white officer who had served under Young in Mexico had complained to his senator in Mississippi about being forced to serve under a “colored commander,” terming it both “distasteful” and “practically impossible.” The senator wrote to President Woodrow Wilson—a staunch Southerner—who asked Secretary of War Newton Baker to look into the problem. Baker, learning of Young’s questionable health, reportedly suggested a medical retirement. Had Young been a white officer, there is every reason to believe he would have been declared fit for duty. But the Wilson administration, which strongly favored a segregated Army, apparently found it expedient to let Young’s condition solve a complaint by white racists.

Young’s old friend Du Bois, joined by the NAACP, continued to lobby for Young’s return to active duty, as did his former commanding officer in the 10th Cavalry, to no avail. While thousands of black Americans eventually served in the Army in Europe in World War I—mostly in the ranks–Young was not one of them. It must have come as a great surprise to the colonel when, just five days before the end of the war, he was recalled to active duty and placed in command of all-black stevedore regiments at Camp Grant, Ill. But his late recall and war’s end precluded any promotion. Young soon again returned to civilian life, but in 1919 he was recalled to duty, again as military attaché to Liberia. He sailed for England in January 1920, accompanied by his wife and two children. Young continued on to Liberia, while his wife, son and daughter went to France to live during his assignment.

Young’s duties in Liberia—advising that nation’s military and supporting U.S. State Department efforts—mirrored those of his earlier tenure. But the War Department also tasked him with intelligence gathering in other parts of Africa, and in November 1921 he traveled to Nigeria, where kidney disease finally caught up with him. He died in Lagos of acute nephritis on Jan. 8, 1922, and was buried in Liberia. After appeals from his widow, the Army returned Young’s body to the United States, where on June 1, 1923, he was buried with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

For further reading Fred Borch recommends Black Officer in a Buffalo Soldier Regiment, by Brian G. Shellum, and For Race and Country, by David P. Kilroy.