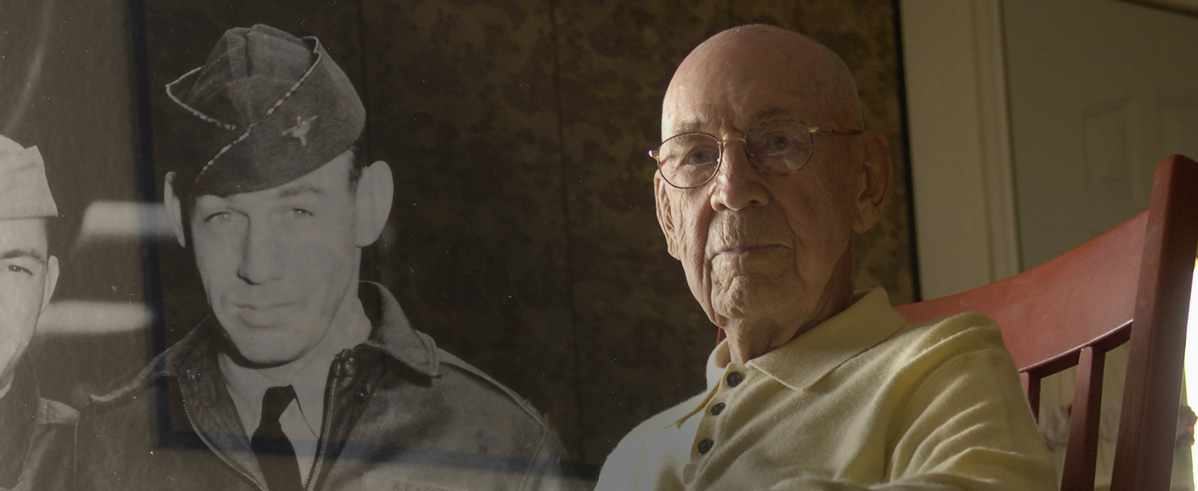

On April 18, 1942, little more than four months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, 80 airmen in 16 modified North American B-25B Mitchell bombers lifted off from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet in the northwest Pacific bound for targets in Japan. The operation marked the first Allied retaliatory strike on the Japanese Home Islands. To plan the daring mission U.S. Army Air Forces Lt. Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold had tapped Lt. Col. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, the famed air racer, test pilot and aeronautical engineer. Doolittle piloted the lead plane from Hornet. His co-pilot was 26-year-old Lieutenant Richard E. “Dick” Cole. Neither Doolittle nor any of his men had flown a single combat mission. On April 9, 2019, retired Air Force Lt. Col. Cole, 103, the last of the famed Doolittle Raiders, died at home in San Antonio. In 2014 Military History spoke with Cole about the bold raid and its surprising aftermath.

We were two days at sea, and the PA system alerted everybody: ‘This force is bound for Tokyo’

Recommended for you

What first intrigued you about flying?

I was born and raised in Dayton, Ohio. As a young kid I used to ride my bicycle from where we lived three or four miles to McCook Field, the Army Air Corps’ first test base. I got to watch all the old-timers. They were testing air refueling, dropping a hose out of one airplane that was higher than another. I also remember the first big bomber, the Barling [Wittemann-Lewis NBL-1]. They had an air race there in which a captain lost his life. I remember reading about [John] MacReady, [Carl] Spaatz and [Jimmy] Doolittle.

When was the first time you went up in a plane?

I went up in a plane at the airport in Vandalia, Ohio, for a dollar. It was a Ford Trimotor.

That must have been a kick.

[Laughs.] It was to me!

What prompted you to join the Army Air Corps?

Well, I graduated from high school in the middle of the Depression, and it was a good job. I had made up my mind earlier I was going to be a pilot or a forest ranger. I enlisted in the Army Air Corps in November 1940, went through training and was sent to the 17th Bombardment Group at Pendleton, Ore.

Did you and your fellow aviators think there would be another war?

It looked like things were going to get a bit tough. But I didn’t really think too much about there being a war in the offing. I enjoyed the job I had.

Where were you when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor?

We were on temporary duty in Augusta, Ga., having a mock war with the Army. Somebody heard it on the radio. We went back to Pendleton, did some modifications and went on sub patrol for a couple of months. We flew a grid system out of Everett, Wash., and Seattle and Portland. Each day we would travel out so far, down so far, then back in. In late December a pilot by the name of Everett Holstrom sank a Japanese submarine off the Strait of Juan de Fuca. In early February 1942 we were transferred to Columbia, S.C.

Conditions at Columbia were a bit rough, yes?

They weren’t too good. The airfield was under construction, and that caused a lot of problems. We lived in tents, and we could only use a certain part of the runways and didn’t have a good parking area for the airplanes. We lived through it.

When did you learn about the Doolittle mission?

The squadron had a bulletin board you had to read every day. I saw a notice they wanted volunteers for a mission, so I put my name there. Well, the whole group and the group commander volunteered.

Where did you train?

We trained at Eglin Field, Fla. It was the biggest Army Air Corps base at that time, with several satellite fields that wouldn’t attract attention. We flew out of those fields. We were confined to base, in isolated barracks, and told not to talk about our training.

Did you even know any specifics?

We knew it would be dangerous, but that’s all.

You’d already trained on B-25s. How did this training differ?

The normal takeoff with the B-25 loaded was somewhere around 3,000 feet. We had to be airborne in 500 feet. Navy Lieutenant (later Admiral) Henry Miller from Pensacola taught us the technique of taking off from a carrier.

Did that prompt any guesses?

We thought we were going to the South Pacific to land in some predesignated area and start fighting the war.

In early March, Doolittle arrived and gathered the crews. What did he tell you guys?

He offered anybody that had volunteered the opportunity to change his mind, without any repercussions. There were no takers.

Who was Jimmy Doolittle to you at the time? What did you know about him?

He was a very well-noted pilot—for his flying skills, number one. He had developed a blind flying technique at Mitchell Field [New York]. He was also the first pilot to perform the outside loop. Doolittle was interested in helping develop the aviation industry and was very education oriented. He was the first man to receive a doctorate of aviation and engineering from MIT.

How did you come to be his co-pilot?

The individual I trained with became ill and had to drop out. So I went to the operations officer, who said, “Well, the old man’s coming in this afternoon—I’ll crew you up with him, and if you do OK, you’ve got yourself a pilot.” Doolittle came in, said, “Fine,” and took the pilot’s seat.

The story goes that Hap Arnold hadn’t intended to let Doolittle fly on the mission, that he’d just wanted him to plan it. Did Doolittle ever tell you about that?

Yes. When he went to report to Arnold, Doolittle told him, “I want to lead the mission.” Arnold said, “I can’t spare you.” They had a few words. Jimmy badgered. Finally, Arnold said, “Well, go see General [Millard “Miff”] Harmon,” who was [chief of staff] of the Army Air Forces. So Doolittle went to his office, stuck his head in the door and said, “Hap says I can lead the mission if you say it’s OK.” Harmon said, “Well, if it’s OK with him, it’s OK with me.” At that point Doolittle closed the door and ran down the stairway. He said that on the way down he heard Harmon said, “But Hap, I just told him he could go!”

What was your opinion of the B-25 as a pilot?

When I reported to the 17th Bomb Group, it had B-18s and -23s. The B-18 was a slow, lumbering airplane, about like a C-47. The B-23 was a bit faster. I don’t know how many of those were built, but there were very few. Then we started to get the B-25, which was really a kick in the air as far as flying. It was like switching from a training plane to a single-engine plane. We all liked the B-25.

How were the B-25Bs modified for Doolittle’s mission?

All excess equipment was taken out, like the Norden bombsight, the lower turret. Mechanics installed a bladder tank in the bomb bay. In place of the lower turret they put another fuel tank. We also ended up with 10 five-gallon cans of fuel in the rear of the airplane. It just about doubled the capacity to 1,100-some gallons.

What about armament?

There were two .50-caliber machine guns in the after turret and a .30-caliber in the nose. The B-25 then didn’t have anything but a plastic tail cone. During training [fellow pilot] Ross Greening suggested we put in two broomsticks, painted black, to fool any fighter trying to jump us from the rear.

What did you use for a bombsight?

Greening came up with a kind of protractor deal with a moveable sight—the “20-cent bombsight.” It worked out OK.

And the bombload?

Four 500-pound bombs. Our airplane had incendiary bombs. Our mission was to light up Tokyo.

Where to from Eglin?

In late March we went to Sacramento Air Depot. Mechanics there started to mess around with the planes—tuned the carburetors, changed the props—which upset Colonel Doolittle. He had a few words with them. From there we flew to Alameda Naval Air Station, Calif.

How many of the group’s B-25Bs made it aboard Hornet?

Sixteen. We backed up alongside the carrier, and a gigantic crane swung around, hooked up to the loading points on the B-25 and hauled it up.

Yet all of the volunteer crews went aboard. Why?

Mainly for secrecy. [Mission commanders] didn’t want to turn those people loose and not know where they were until the mission was over.

Doolittle let you have one more night on the town?

Yes. An admiral’s gig came alongside the dock, and we went across to San Francisco to the Top of the Mark [on Nob Hill]. We wondered where the Japanese spies were, because you could look across the bay and see the carrier with all the B-25s on it.

You left port on April 2, 1942. Describe the scene.

When we began to steam away from Alameda, it was pretty foggy, but by the time we got around to the Golden Gate Bridge—which most of us had never seen—the sun broke through the clouds.

When did you finally receive mission specifics?

We were two days at sea, and the PA system alerted everybody: “This force is bound for Tokyo.” We were pretty excited—above all happy to know what we were going to do. Things quieted down as people began to realize what they were getting into.

Initially, the Navy people weren’t very happy with us, because we were upsetting their routine, had blocked off some passageways. But when they announced what our mission was, why, they couldn’t do enough for us.

We joined up with the task force en route, someplace abeam of Hawaii.

Cruisers, destroyers and the carrier Enterprise, yes?

Yes. The Navy airplanes on Hornet had to be put down on the second deck. There wasn’t space for any B-25s. One of the reasons Enterprise went along was that it had fighter airplanes, in case we had a meeting with the Japanese.

Who commanded the task force?

Halsey. Admiral [William F. “Bull”] Halsey.

How close to Japan was the Navy supposed to get you?

Maybe 400 or 500 nautical miles.

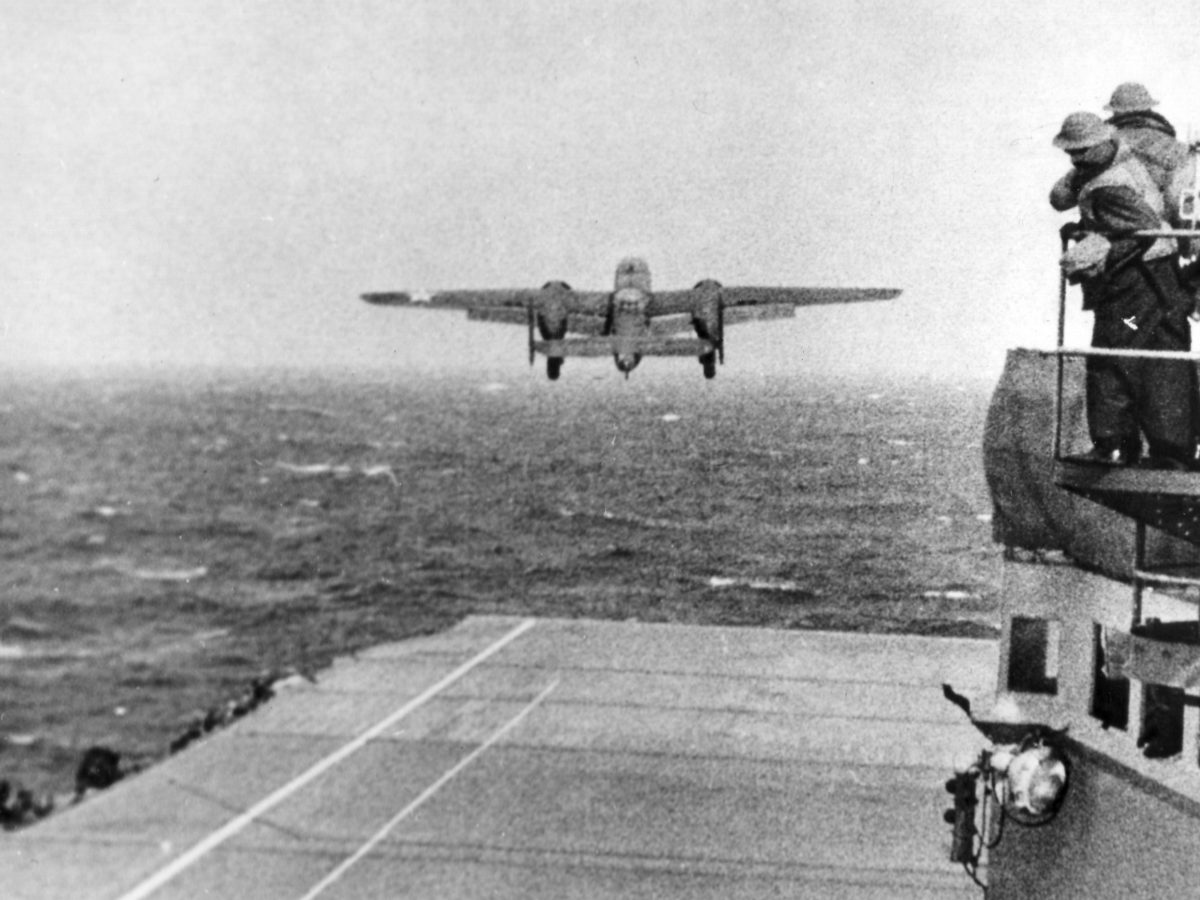

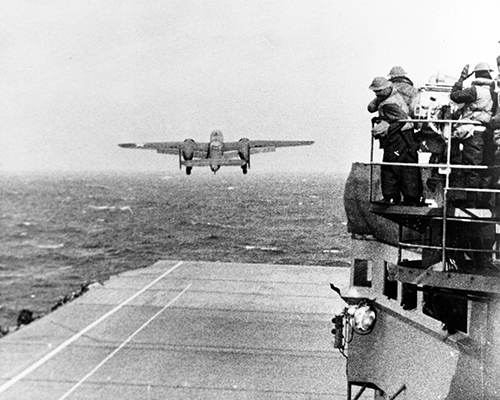

But you launched early, on April 18. Why?

The Navy ran across a Japanese picket ship, Nitto Maru, and Halsey made the decision we would launch. I was on my way to breakfast, when the PA announced, “Army pilots, man your planes!” Paul Leonard, the crew chief, was already there. We took the engine covers off the plane, pulled the props through and went over the checklist. We were all set when Doolittle came.

How far from Japan were you?

Around 650 nautical miles.

How were conditions?

Well, it was pretty rough. Water was coming up over the bow and causing problems, with the airplanes beginning to slip around on deck.

Were there any injuries or damage?

The only incident I know of came when [Doolittle and I] were already gone. A Navy lad [Robert W. Wall] slipped and went underneath a propeller, which cut off one of his arms.

But the wind worked to your advantage, yes?

Definitely. The carrier speed was between 20 and 35 knots forward, and the wind was pretty close to about the same amount. So you didn’t have to generate a lot of forward movement when taking off.

Describe the launch procedure.

We placed the B-25 in the middle of the deck, with about seven feet between the right wingtip and the ship’s island. The Navy had painted a white line down the deck for the left main gear and another for the nose gear. We taxied up and revved the engine. A launcher picked the appropriate time, the peak of an up movement with the water, and the carrier just dropped out from underneath the airplane. We got off a good 20 or 30 feet from the end of the deck.

Did the group fly in formation?

We couldn’t afford to because of the fuel. The only other plane we saw was the second, piloted by Travis Hoover.

What was your flight time to Japan?

A little over four hours. We tried to maintain 168 mph indicated. Our average altitude was 200 feet. We veered to avoid freighters, and a Japanese four-engine flying boat flew over us, but we weren’t discovered.

We shored in north of Tokyo. It was a bright, sunny day. People were out on the beach. Nobody seemed to care when they saw us. One reason was the Japanese had an airplane called the “Nell” [Mitsubishi G3M] that looked something like a B-25, with two tails. We think they thought we were one of their airplanes.

Turning south toward the city, Colonel Doolittle pulled up to 1,500 feet, Fred Braemer dropped the bombs, and we went back down on the deck. We got jostled around a bit by anti-aircraft, but I don’t think we received any hits.

That’s some first combat mission.

Yeah! [Laughs.] Well, of course, we didn’t know any better.

The raid was designed to do two things. One was to let the Japanese people know their leaders were not being truthful by saying Japan couldn’t be bombed by air. The other was to give the Allies, and particularly the United States, a morale shot in the arm

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Your destination was China?

Yes. We were supposed to land, gas up and go on to western China. The Army Air Corps would end up with a squadron of B-25s and a commander. It didn’t turn out that way.

All of the airplanes made it to China, except one that had excessive fuel loss and landed in Vladivostok, Russia.

What happened to its crew?

Well, [Soviet Premier Joseph] Stalin didn’t want to get involved in the war with Japan, so he played the political game and put those people under house arrest for 13 months.

And your plane?

Several hours past Tokyo navigator Hank Potter passed a note up to us that we were going to end up about 180 miles short of China. The weather was very bad—a lot of lightning, rain. But the warm front had developed a “kamikaze wind,” from east to west, and that gave us the tailwind to China.

We were all supposed to land in Chuchow, but there were complications. The airplane carrying a portable homing station crashed on the way there. And the Chinese, on hearing our engines, thought we were Japanese and turned off electricity [to the lights], which we couldn’t use anyway because of the weather.

What did you do?

The only thing we could do was fly until we ran out of gas and then bail out. It was dark, and we didn’t know anything about the terrain except that it was mountainous, but that was the only alternative, unless you wanted to commit suicide. We bailed out at around 9,000 feet. You’re supposed to count, “One thousand…two thousand…three thousand,” then pull the rip cord. I think I said, “One thousand,” and pulled. I pulled it so hard I gave myself a black eye.

Where did you land?

My parachute drifted over a pine tree, and I spent the night in the tree. Don’t think I slept. I know I dozed off.

How did your crewmates fare?

Everybody bailed out successfully. We all had compasses and knew we needed to walk west rather than try to go east. By chance we were all together the next night.

What was Doolittle’s mood?

Real worried. He thought the mission had been a failure, because he’d lost all the airplanes and some of his people. He was really down in the dumps.

Had the mission failed?

The raid was designed to do two things. One was to let the Japanese people know their leaders were not being truthful by saying Japan couldn’t be bombed by air. The other was to give the Allies, and particularly the United States, a morale shot in the arm.

The damage we did wasn’t much. But the raid caused the Japanese to bring back forces from down around Australia and India and concentrate their power in the Central Pacific. They also transferred two carriers to Alaska, and that evened the odds with the U.S. Navy at Midway. Japanese naval forces were at a disadvantage from then on. It was a turning point in the war.

What happened to the Chinese?

We couldn’t have done it without their help. They did everything they could to keep the Japanese from capturing our crews. But according to historians, the Japanese killed over 250,000 people.

Did you feel like heroes?

No, we were just doing our job, part of the big picture, and happy that what we did was helpful. We couldn’t have done it without the Navy. They risked two of their carriers and quite an armada.

How were you recognized?

We received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

And Doolittle the Medal of Honor?

Yes. He deserved a lot more.

What was your opinion of him as your commander?

The highest order of respect from one human being to another.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.