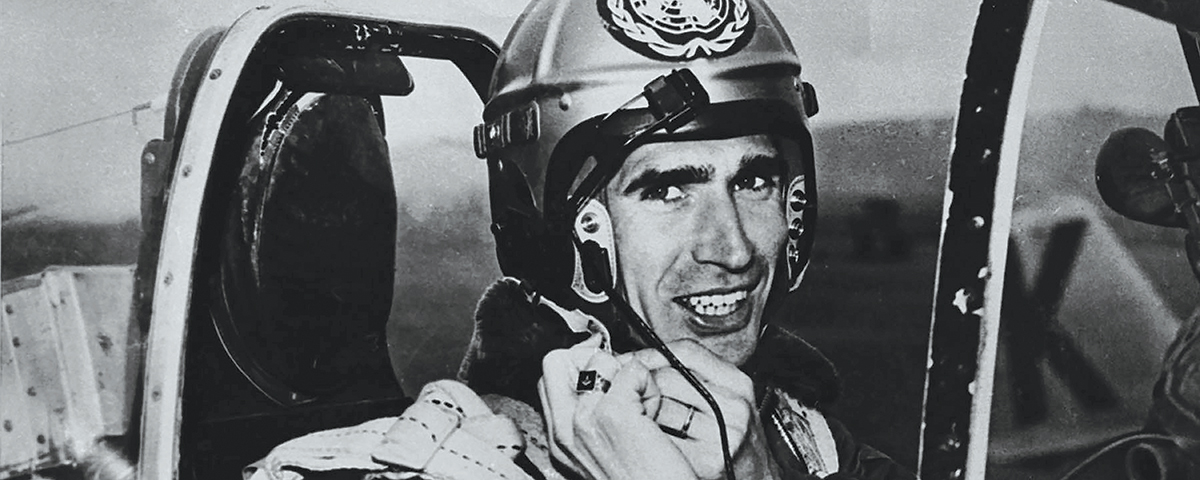

Ordained minister Dean Hess dealt death from the sky as a fighter-bomber pilot, but never lost his humanity.

Captain Dean Hess, a man of God piloting a lethal killing machine, scanned the German city beneath his Republic P-47D Thunderbolt. Born and raised in Marietta, Ohio, Hess had been trying to save souls since he began preaching at the age of 16. Yet in December 1944 his mission was to destroy Nazi forces in support of Allied troops advancing into the Reich.

Kaiserslautern, an important industrial city, had already been worked over by Allied bombers, making it difficult to find inviting targets. Hess and flight leader Bill Myers had ventured away from their squadron to check out the city’s railroad marshaling yards. Amid bursts of flak, they were rewarded by the sight of two trains in the yards.

After a strafing run with their .50-caliber machine guns, Hess followed his leader down to deliver the 1,000-pound bombs they carried under each wing. His first bomb launched cleanly and speared toward a locomotive below. The second was slow to release. Pulling out of his dive, Hess glanced back through his bubble canopy in time to see the bomb plunge into a neighboring seven-story building, followed by an explosion. “I wondered whether I had killed anyone,” he recalled in his autobiography, Battle Hymn, “but I was more concerned whether I had fulfilled my mission.”

Weeks later, touring the occupied city in a jeep, he was stunned to learn that the building he struck had served as a school for orphans, and that a number of them had been killed during his attack. He looked up at the gutted structure, “trying to keep my eyes away from the black hole where my bomb had hit,” he wrote. “But it seemed to stare at me like some malevolent eye.”

Images of that bomb damage, burned into his memory, would trouble him for the rest of his life. But in another war six years later, it would also help motivate him to play a key role in saving hundreds of war-orphaned children half a world away in Korea.

Like so many youngsters of his era, 9-year-old Dean Hess was inspired by Charles Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927. Hess mowed lawns and delivered newspapers to earn the $2 required to take a brief flight from a nearby airfield. Surprised by the exhilaration he felt as the Piper Cub soared through the sky, he landed convinced that aviation would play a role in his life.

Young Dean embraced another commitment: to Marietta’s Disciples of Christ Church, where a minister challenged the devout 16-year-old to preach at a service. Hess stumbled through the sermon, vowing to do better the next time. He felt a calling to preach, and wanted to attend college to help advance himself into the ministry. But he struggled to raise money, often working seven days a week pumping gas. A coworker introduced Dean to his sister, Mary Lorentz, and the two fell in love.

The youth finally scraped together $86 to begin classes at Marietta College. The college offered a surprising bonus: a federally subsidized pilot training program. So, with an instructor in the front seat, Hess was soon soaring again from the airfield. Years later he would tell a writer for Life magazine that “the sensation of flight brought me many times closer to God.”

After graduation in June 1941 and his ordination as a minister, Hess found that flying could transport him more quickly to the widely scattered churches whose congregations began hiring him to preach. He became an airborne “circuit rider,” visiting Ohio churches not on horseback but at the controls of a rented lightplane.

Hess took a factory job in Cleveland to pay off his debts and lay a financial foundation for his future with Mary. Their marriage, and his life’s mission as a man of the cloth, seemed within reach.

Yet at an evening service at the Hanover church on Sunday, December 7, 1941, he told astonished parishioners that he wouldn’t be preaching to them again for a long time. At a time when so many young men would be enlisting to defend their country, he couldn’t accept deferment as a chaplain. He was joining the war effort as a fighter pilot.

Hess completed advanced training at Napier Field in Dothan, Ala., where he and Mary wed immediately after the ceremony commissioning him as an officer. A ring from the post exchange cost him $60 but, as he told her later, “It was the greatest bargain I ever made.”

His natural flying skills helped keep him at Napier as a flight instructor for two years. When officers learned he was also an ordained minister, he was designated acting chaplain. In that role he learned that, thousands of miles from the battlefront, he was still close to the tragedy of war. Twice he had to tell young wives that their husbands had died in training crashes.

Having signed on for hazardous duty, Hess was eventually assigned to the Ninth Air Force in France, supporting U.S. Army divisions pushing the Wehrmacht back into Germany after D-Day. To his dismay, he found the squadron’s flight line at St. Nazier monopolized by P-47Ds, which he had never flown. Hurriedly quizzing more-experienced airmen and reading everything he could find about the rugged, heavily armed Thunderbolts, he fended off efforts to return him to England for further training.

Soon Hess joined the seasoned pilots attacking German ground units. As a minister he had told parishioners that killing was a grave sin, so he was surprised to discover that he was very good at it. German soldiers, he explained, “bobbed up before my guns with unaccountable persistence.”

In the absence of a regular chaplain, Hess agreed to conduct services for the enlisted men and, later, for his fellow officers. Inevitably some dubbed him the “Flying Parson.”

With Allied troops closing in on Berlin in the spring of 1945, Hess returned to Ohio with a Distinguished Flying Cross to await redeployment to the Pacific. But the Japanese surrender freed him to resume civilian life. His determination to further his education took the family to Athens’ Ohio University, where he received a master’s degree in June 1947. He then moved on to Ohio State to begin work on his doctorate.

In the spring of 1950, he was invited back into service, offered a major’s rank and eventually rotation to Japan. It was a difficult decision because this time he was leaving not only Mary but also sons Larry and Edward (a third son, Ronald, would join the family in 1956). Still, with trouble brewing in Asia, he was soon saying goodbye to his family at New York’s LaGuardia Airport as he departed for Japan and threats of a new war.

On June 25, 1950, Communist North Korea Premier Kim Il Sung unleashed nine divisions, supported by Soviet-supplied heavy armor, into the Republic of Korea (ROK) in a surprise effort to subjugate the U.S. ally. South Korea’s military, armed with largely obsolete weaponry and virtually no air support, melted southward. The outgunned ROK forces and equally unprepared U.S. Army troops who were rushed in from Japan to help were pushed relentlessly down the peninsula.

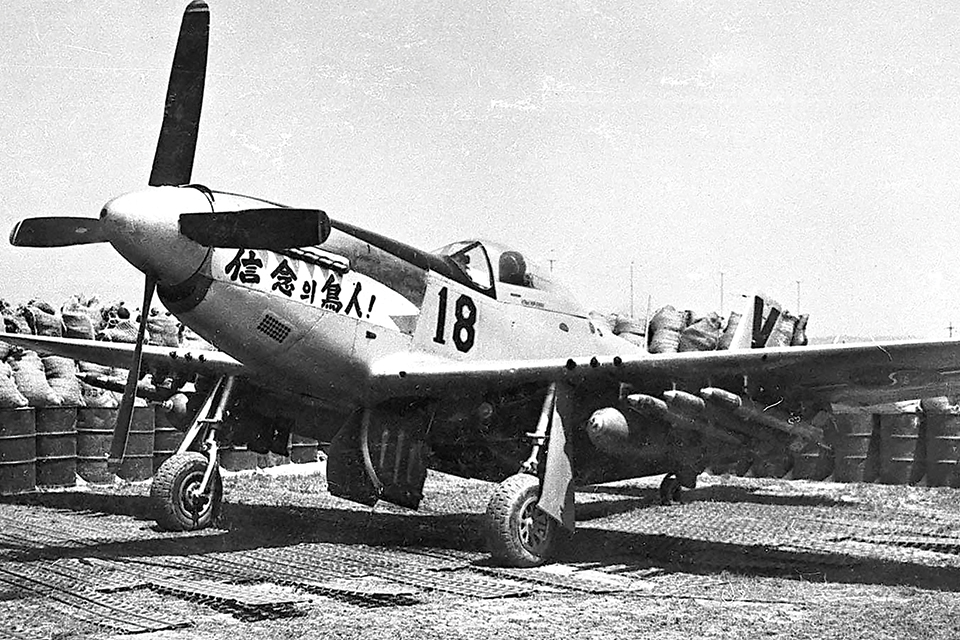

Major Hess accepted an unexpected offer to command and upgrade the nascent ROK air force, a base support unit equipped primarily with aging trainers. His challenge was to transform the unit’s pilots and maintenance personnel into a lethal air wing. Hess was ordered to Taegu, south of the ROK capital of Seoul, in advance of American volunteers who would help train the South Korean pilots to attack ground targets in 10 World War II–vintage North American F-51D Mustangs.

Hess and his volunteers flew a C-47 from a Japanese base to Taegu on July 4, carrying any equipment and supplies they could beg, borrow or “midnight requisition” to support the mission. The Taegu base would be the first of seven they improvised and occupied during the next six months as the war ebbed and flowed along the peninsula.

When the major’s personal Mustang arrived from Japan, he asked an artistic crewman to paint “By Faith I Fly” on the engine cowling in Korean characters. In Europe he had labeled his P-47D with a similar message in Latin (Per Fidem Volo) to show clearly that, amid all the killing, the Flying Parson retained his faith.

Hess’ American volunteers took pride in their assignment, but they would pay a heavy price for their efforts. Of the 10 American pilot officers who volunteered to serve with the training unit, seven were killed during the first year of war.

The unit would also lose several ROK pilots, including a veteran who had flown Zeros for Japan against U.S. aviators in WWII. The pilot, who had been checked out in the F-51 only once, didn’t realize it couldn’t maneuver as nimbly as the Zero. Unable to pull out during a low-level attack maneuver, he plowed into the ground near his target.

Although the American instructors were under orders to serve solely as advisers, Hess quickly determined that the only way they could train the pilots, who spoke little English, was to accompany them on raids. He won official approval, and excited support from the pilots, for what he called “on the job training.”

Just seven days after Hess flew into Taegu, a lookout reported that a massive North Korean convoy was moving southward toward a mountain pass held by Army troops. Air support was urgently required, and U.S. Air Force units in Japan couldn’t get through the severe weather in time to help.

With heavy rains drenching a wide area, Hess and one volunteer, a Lieutenant Timberlake, took off in F-51s loaded with bombs, rockets and machine gun rounds. They soon came upon a North Korean armored division snaking its way down a narrow mountain road, intent on destroying the U.S. 25th Infantry Division.

Hess signaled Timberlake to attack the rear end of the convoy while he bombed the lead vehicles, halting traffic. “We buttoned them up with bomb craters and knocked-out vehicles at either end,” Hess said. As the weather cleared, the pilots circled, awaiting reinforcements. Only after their ROK colleagues began arriving from Taegu, followed by Air Force F-80s, F-82s and B-26s from Japan, did the pair head back to Taegu to refuel and reload for two more attacks on the convoy.

By the time Hess headed home for the day, the convoy was a smoking ruin. An Air Force assessment tallied 117 trucks, 38 T-34 tanks and seven half-tracks destroyed and “countless enemy dead.” Earle E. Partridge, commanding general of the Fifth Air Force, described the action as “a turning point of the war.”

As enemy forces continued to advance down the peninsula, Hess’ unit relocated to Chinhae in the shrinking Pusan Perimeter. Hess and a handful of volunteers flew mission after mission to slow the North Koreans, with the major flying as many as six different F-51s in a single day, strafing and bombing the invaders and then returning to base for a freshly armed fighter. “The man walks on water,” observed Lieutenant Ernest Craigwell, a Tuskegee Airman veteran who joined Hess’ command in June 1950.

In one solo action, Hess helped an isolated 18-man American patrol claw its way back to friendly lines. Diving time and again with guns blazing, he cleared a path for the soldiers to fight their way to safety. For that day’s work, he was awarded a Silver Star. Even Communist radio propagandist “Seoul City Sue” gave him unintended praise when she denounced him as the “Barbarian of Chinhae.”

While Hess was targeting Communist troops moving south toward the war zone, a liaison pilot called his attention to a group moving down the main highway. Because of the hazy conditions, Hess requested and received assurance that they were enemy troops. Diving at more than 300 mph, he fired one short burst before he saw women and children diving for cover in a roadside ditch. “Those were refugees!” he shouted at the liaison pilot. Memories of Kaiserslautern flooded back, but it was too late to recall his bullets.

Abruptly, the tide of war turned in Korea. In September 1950 U.N. forces regained the initiative, recapturing Seoul and pursuing the North Koreans across the 38th Parallel toward their border with China. But although General Douglas MacArthur assured President Harry Truman that there was “very little” chance of Chinese intervention, and memorably promised his soldiers they would be home for Christmas, swarms of Chinese troops attacked across the border in a devastating November blitz.

With his squadron operating near the border, Hess promptly directed a raid that destroyed 40 invading vehicles in half an hour. Yet it was a hollow victory in the face of the Chinese surge, which wiped out some U.N. units and forced the 1st Marine Division into a desperate fighting retreat from the Chosin Reservoir. The U.N. forces eventually fell back to a line near the 38th Parallel, where they were able to halt the Chinese advance.

The rapidly changing front gave Korean civilians little opportunity to flee cities left vulnerable when U.N. troops were forced to retreat. Parentless children foraged amid the ruins. Allied units, including Hess’, began sharing food and other essentials with the ragged tots. When U.N. troops initially recaptured Seoul in 1950, they had transported displaced children to a local orphanage. But with Communist troops besieging the capital again, Fifth Air Force chaplain Russell L. Blaisdell warned Hess against sending more children to that orphanage. The chaplain sought a new sanctuary for the homeless boys and girls, and Hess suggested Cheju (now Jeju) Island off the southern Korean peninsula, where ROK air force pilots’ families were already being sheltered. Hess thought a nearly deserted agricultural school on the island might temporarily house the orphans.

The two hurriedly collaborated on a plan to transport orphans to the island. Blaisdell commandeered enough military trucks to deliver almost a thousand orphans and 80 orphanage staff to the seaport at Inchon. But a promised Korean navy LST never arrived to ferry the group to Cheju, leaving the children shivering on the docks in bitter cold. “Everything was in readiness at Cheju Island,” Hess recounted, “but now the gate to safety was banging shut.”

The following day, December 20, orphans and adults who had been trucked back to Seoul’s Kimpo Airport were waiting, near despair, when a distant rumble grew into a roar that filled the winter sky. Responding to Hess’ urgent appeals, General Partridge had dispatched 15 C-54 Skymasters from Japan to Kimpo carrying doctors and nurses with blankets and medicine. The children were hurriedly treated and the fleet thundered off to Cheju in an airlift that war correspondents promptly labeled “Operation Kiddy Car.” Volunteers were mobilized on Cheju to help the children when they arrived. “I never thought I’d feel a greater thrill of gratitude or relief,” Hess observed, “than when I saw the last ragged little figure disappear inside the last plane.”

With the Korean War in a standoff and newly elected President Dwight Eisenhower eager to end the carnage, an uneasy armistice finally halted the killing in July 1953 and reestablished the border roughly along the 38th Parallel. Lieutenant Colonel Hess and his surviving U.S. volunteers had relinquished their responsibilities to officers of the upgraded ROK air force, which had become autonomous from the USAF in January 1952.

Hess had reluctantly left his ROK command in June 1951 for reassignment after 250 missions, miraculously spared injury. President Syngman Rhee presented him with Korea’s highest military award. From his ROK pilots Hess accepted a sword once owned by one of their countrymen who had died in combat. Then he visited the Cheju orphanage for tearful goodbyes from the children and staff before he returned to the States.

After a leave in Ohio, Hess reported for duty as the Fifth Air Force’s information officer in Texas, one of numerous assignments that would take him, Mary and their sons to posts across the country. Besides continuing his support for the Cheju Island facility, Hess led fundraising efforts for a new Orphans Home of Korea in Seoul. He and Mary contributed thousands of dollars in royalties from his 1956 memoir Battle Hymn and the movie of the same name, starring Rock Hudson as Hess. Hess flew an F-51 in the film and served as technical adviser.

Hess returned to Seoul in 1960 on a very special mission: to pick up an orphan, about five years old, that he and Mary were adopting. The Hess family embraced the girl, whom they named Marilyn. Though proud of her Korean heritage, she would quickly master English and grow up as a typical American teen.

Returning home to Ohio, Hess served at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base until his retirement as a full colonel in 1969. His flight helmet and Korean military medal remain on display at the adjacent National Museum of the U.S. Air Force. After military retirement he taught for five years at a local high school. Mary died in 1996.

Two years after Hess died at 97 on March 2, 2015, South Koreans dedicated a towering memorial on Jeju Island to the colonel who had risked so much to protect their independence and save their children. The ceremony at the Jeju Aerospace Museum drew some 200 government and military officials, war veterans and former orphans. An understated inscription on the monument sums up in just three lines Hess’ contribution to the people of the Republic of Korea:

Hero of the Korean War

Godfather of the ROK Air Force

Father of War Orphans.

Veteran journalist and aviation writer Don Bedwell is the author of Silverbird: The American Airlines Story. Further reading: Hess’ Battle Hymn.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!