On April 19, 1914, striking coal miners in a tent camp at Ludlow, Colorado, many of whom were Greek immigrants, celebrated Orthodox Easter with their families, singing along to accordions and mandolins. The day was bright and the music infectious. Some dressed in traditional outfits. Fellow tent city residents—Italians, Slavs, Croats, Mexicans, and others—joined in. Children and chickens and dogs ran across the dusty ground between the tents. On the camp baseball diamond a game took place, men against women. That night there was a dance.

The United Mine Workers of America had built the camp at Ludlow the autumn before, after the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, owned by magnate John D. Rockefeller Jr., threw striking miners out of company town housing. The men, employed at a Rockefeller mine in Trinidad, about 20 miles south of Ludlow, had been pressing coal companies in the area owned by the Rockefellers and others for better pay and working conditions. On Sept. 23, 1913, Colorado Fuel formally refused to acknowledge any of the miners’ demands. More than 9,000 men walked out. Management immediately evicted strikers and their families, leading to the tent city’s construction. The strike was in its seventh month.

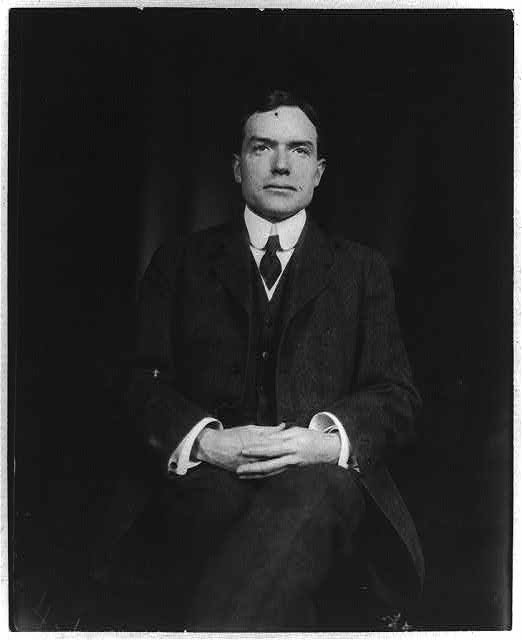

The Rockefeller family owned several coal mines in southern Colorado. Founder John D. Rockefeller had entrusted management of the Colorado Fuel mines to his son John when the younger man was in his late twenties. Rockefeller Jr., 31, was thought shy and a practitioner of his father’s strict Baptist theology and habitual penny-pinching. He displayed none of the extravagance associated with other wealthy scions. The Rockefellers had a reputation for lacking scruples and leaving management of their vast holdings to hardnosed local managers. That was the case in southern Colorado.

The strikers camped at Ludlow had neighbors. A set of Southern and Colorado Railway tracks separated the miners’ white tents on the east side from brown tents to the west occupied by state National Guard troops activated the preceding October by Gov. Elias Ammons. With tensions high, the strikers and the Guard had agreed to regard the depot beside the tracks as neutral territory. On Easter Monday morning, more than 20 uniformed Guardsmen were on duty. Ordered to serve as neutral observers, the Guard force had been infiltrated by hoodlums working for Colorado Fuel and Iron. These men, itching to fight, tended to generate violence.

Gunfire, its source unknown, began at 9:30 that morning, continuing all day and into the night, when mine guards torched the tent city, setting off 10 days of destruction, gunplay, and loss of life on the southern Colorado coalfields. Only when President Woodrow Wilson sent federal troops did the fighting stop and the mines reopen. The strike ground on until December 1914, exemplifying the bitter divide between wealth and workers in America. The Ludlow strike has been called the bloodiest labor conflict in American history.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Hard WOrk

Miners in southern Colorado were mostly immigrants, many from Europe, who arrived without skills, lured by coal company recruiters’ stories of jobs and wide-open spaces. The men of the workforce spoke more than 20 languages. Striving to keep them compliant and unorganized by complicating communication, management scrambled every shift’s ethnic and cultural makeup. The United Mine Workers of America, founded in 1890 and already established in the East, was trying to expand into the West, so far without success. In 1902 miners nationwide walked out. Trying to end the standoff, President Theodore Roosevelt formed a federal commission. The resolution did not favor the union. Subsequent strikes in West Virginia gained no significant advances. The UMW, whose chief organizer in southern Colorado was John Lawson, wanted immigrant miners there to recognize their shared injustices—and to join the union for a nickel a month in dues.

An ambitious migrant from Greece caught Lawson’s eye. Louis Tikas, born on Crete, was short and stocky, with a commanding manner. Said to be college educated, he spoke several southern European languages. Lawson hired him to help spread the union gospel. Tikas solicited fellow workers’ complaints, encouraging them to join. The polyglot workforce began to see him as a leader.

The United States ran on coal, which heated houses, powered locomotives, and, converted to coke, was integral to steel production. Electricity generated by coal-burning steam turbines lit cities. Much of that coal came from Colorado, which in 1913 had the nation’s highest fatality rate among miners. State law nominally limited shifts to eight hours. Owners ignored the law. Men often worked 12 hours or more a day. In September 1913 a miner made about $3.50 a day, or $690 a year, based on his output, measured by the ton as weighed by company inspectors who often cheated workers. And then there was “dead work” — repairing structural supports, clearing passageways, and setting tracks for mule carts that hauled fractured coal out of the earth. Any time a man was not digging with a pick at the coal face he was assigned these chores at no pay.

Mining companies often paid in scrip negotiable only at company stores, the sole local sources for blasting powder, lamps, and tools, which miners had to buy themselves. Company stores, which returned a 20 percent profit, charged $1.50 for overalls an independent retailer sold for fifty cents. In the same vein, company towns were closed systems designed to milk the work force. Some dwellings were shacks, others were four-room cinderblock structures rented for $2 a room per month. Schools, churches, saloons — all were company-controlled, down to how many drinks a barkeep could serve a customer. Barbed wire enclosed some towns.

Along with being shortchanged, miners complained about heavy-handed security. For guards Colorado Fuel and Iron contracted with the Baldwin Felts Detective Agency, whose employees were notorious for administering beatings, harassing miners’ wives, threatening to use their guns, and committing murders. The UMW wanted an end to the guard system, better pay and safety controls, and recognition of the union. Miners wanted to elect their own coal-weight men and to shop where they liked. When the union asked to meet with management regarding grievances, a Denver-based Colorado Fuel manager alerted Rockefeller in New York.

“We absolutely refuse to even meet with these agitators,” the manager wrote.

Rockefeller already had received a letter warning of a strike; he marked the message “Irrelevant” and set it aside.

The Walkout

On Wednesday, Sept. 23, 1913, under heavy rain that became sleet and snow, thousands of miners across the southern Colorado coalfields walked out. Evictions began immediately. Displaced families headed for tent cities set up by the union at Ludlow and other locations. A Denver reporter watched the trek.

“Little piles of rickety chairs … miserable looking straw bedding,” he wrote. “These were the contents of the homes of the miners whom the mine owners have called prosperous and contented.”

The Ludlow camp had 200 12-foot-by-14-foot canvas tents with wood floors to house 1,200 strikers and their families. To facilitate contact between organizer Louis Tikas and the UMW offices in Trinidad, his tent had a telephone. Each tent had a stove. Residents shared privies. Flags of the more than 20 nationalities represented flew above the site, which had a baseball diamond and a big tent for holidays, dances, and religious services, as well as a refectory and a communal oven. To the south of the tents lay the Ludlow train depot where a Greek bakery, two stores, a couple of saloons, and a post office served the strikers. The union provided weekly wage relief: $3 per man, $1 per woman, and 50 cents for each child. Many miners kept guns and, fearing attacks, dug pits beneath their tents’ floors as hiding places in case of violence.

Colorado Fuel guards harassed the strikers, patrolling in an armored car known as the “Death Special” on which was mounted one of the company’s four machine guns. At night searchlights disrupted residents’ sleep. The miners retaliated by destroying mine tipples, housing reserved for strike-breakers, and other property. Wives and children joined miners in shouting at guards and strike-breakers disembarking at the depot. After several incidents, some violent, Gov. Ammons deployed the Guard in late October. The unit, led by Gen. John Chase, did little to restore peace. Chase filled the ranks with mercenaries. Strikers collected firearms and ammunition.

In November, hoping to negotiate an agreement, Ammons summoned three union representatives and three company officials. The operators claimed the UMW was trying to force unionization onto a contented workforce. The miners told of having to toil in foul air, bribe superintendents to get shifts, perform dead work for no pay, and endure accidents caused by company negligence. The conference ended without a deal.

Ammons deferred to Gen. Chase on how to use the Guard, which Chase interpreted as authorizing him to impose martial law. He arrested strikers without legal basis and issued a directive allowing management to hire more strikebreakers. In March a man was murdered in the tent colony at Forbes, south of Ludlow. Chase, “to forestall further outlawry,” destroyed the Forbes community’s tents. One woman turned out of her home into the snow saw her newborn twins perish from the cold.

News of the conflict reached Washington, D.C. In March 1914 the U.S House Committee on Mines and Mining held hearings in Denver and Trinidad. On April 6 the committee called witnesses in Washington, including John D. Rockefeller Jr. Committee Chairman Martin Foster (D-Illinois) grilled the young tycoon on the lives of miners on his payroll. Rockefeller said he relied on his Colorado managers for information.

“These men have not expressed any dissatisfaction,” he told the committee. “The records show that the conditions have been admirable.”

Rockefeller admitted not having visited his southern Colorado holdings in 10 years and said he had not met with CFI’s officers since the strike began. Mary “Mother” Jones, a legendary union organizer who despite advanced age had been participating in the Colorado confrontations, also testified, decrying the miners’ plight.

A Shooting

In Ludlow on the morning of Monday, April 20, 1914, a National Guard officer asked to meet with Louis Tikas at the depot. Tikas, 28, got his fellow workers to promise that while he was with the Guard officer they would remain calm. The two met at 8:50 a.m. Armed National Guard reinforcements on horseback galloped into sight, spurring the miners to get their guns. Shooting began. Women and children hid, many in a well north of the camp. Others headed south to an arroyo. Some took shelter in the makeshift bunkers miners had dug beneath their tents.

Tikas was everywhere — checking on families, shouting instructions to miners in the arroyo, and from his tent phoning union headquarters in Trinidad seeking guidance. An Italian miner running toward the well was struck by four Guard bullets and fell, mortally wounded. When the Snyder family, with six children, fled their tent, son Frank, 11, was shot through the head. The family, the father with his dead son over his shoulder and carrying his toddler daughter, spent the night at the depot waiting for a train out of town.

As a 36-car train headed south on the tracks its bulk shielded some miners and their families from gunfire. A brakeman aboard the train later recalled seeing women and children racing for cover and a guard torching the minders’ camp. Gunfire continued into the evening. Tikas, lacking reinforcements, told the men in the arroyo to retreat east to the hills. As Tikas started toward the tent camp Guard officers grabbed him, smashed his head in with a rifle butt, and put three bullets into his back.

As Tikas’s funeral, in Trinidad, was drawing 2,500 mourners, the true horror of the Easter Monday violence was coming to light. At the torched camp on Tuesday, April 21, the Ludlow postmistress encountered a distraught woman raving about dead mothers and children buried in a pit. She found another woman similarly distressed. The postmistress put the two women on a train to Trinidad and looked around but found nothing. The next day, beneath the rubble and ashes of a burned tent and its flooring, searchers found the corpses of two women and 11 children, all asphyxiated.

Mary Petrucci, found wandering the camp on Tuesday, had taken refuge in her neighbors’ pit with her three children, including a six-month-old. Also in the improvised hideaway were Alacarita Pendregon with her two children; Patricia Valdez and her four children; and Cedilano Costa, several months pregnant, and her two children. When the tent above burned, smoke made Mary unconscious. Hours later she revived, saw her children lying dead, and crawled from the pit. Pendregon also survived, leaving behind her lifeless infant and son. In all more than 20 died that day

Anger Grows

Word of the deaths further mobilized miners. Stores in Trinidad and surrounding towns sold out of guns and in Trinidad the union openly distributed arms. Reinforced by thousands of miners from across the area, men of the Ludlow camp set fire to mine buildings and tunnels, destroyed railroad bridges, and broke into company stores to steal weapons. Gov. Ammons was in Washington, D.C., discussing water rights when his lieutenant governor summoned him home to manage the coalfield conflict. Ammons enlarged the Guard force. Gen. Chase now commanded 650 men spread along the 20-mile-plus strip of mining towns. The raging strikers, sometimes 300 at one location, made guerrilla-style attacks on six mines and company towns.

The siege was impoverishing the state and the union. Colorado had paid the National Guard more than $600 million by the time Ammons, who had come to be seen as weak and a tool of the mine operators, asked President Wilson for help. Wilson personally urged young Rockefeller to negotiate with the UMW and was appalled when he refused. The president, who was in the midst of a U.S. incursion at Vera Cruz, Mexico, had committed much of the nation’s military to that operation. Nonetheless Wilson sent 1,600 U.S. Army cavalrymen to southern Colorado with orders to quell the violence while remaining neutral. The soldiers disarmed both sides, closed coalfield saloons, and in December 1914 restored peace.

To end the strike and save face for the union Wilson proposed a federal commission on ways to prevent labor conflicts. The union, which had spent an estimated $870,000 during the strike, came away empty-handed: no raises, same terrible working conditions, no union recognition. Estimates of fatalities during the months of rampage ranged as high as 199. But the strike had shown the miners and the public the need for labor reform, and in time union membership and solidarity grew. One miner said afterward that the Colorado strike left those who endured it “real close…just like a big family.”

AFTERMATH

Created in the wake of a 1910 bombing by iron workers union members of the Los Angeles Times headquarters to analyze causes and effects of labor strife, the federal Commission on Industrial Relation investigated the Colorado Fuel and Iron walk-out and other strikes that occurred during 1914-15. In its testimony, the company flatly blamed the miners: “Without a doubt the women and children who lost their lives in the affray were smothered in a covered cave, through the foolish, if not criminal, act of their men who put them there and sealed the cave with dirt.”

Gen. Chase claimed his National Guardsmen had made “truly heroic” efforts to help women and children during fires at Ludlow. Facing hostile questioning by commission chair Frank Walsh, a prominent progressive lawyer, Rockefeller displayed a revised attitude toward labor. He said he had never directed activities at Ludlow, blaming subordinates for the events. He did not repent but alluded to a new sense of moral responsibility at Colorado Fuel.

Union organizer John Lawson excoriated Rockefeller: “Out of his mouth came a reason for every discontent that agitates the laboring classes in the United States today.” As for Rockefeller’s philanthropies, Lawson said, “Health for China, a refuge for birds, food for Belgians …. and never a thought of a dollar for the thousands who starved in Colorado.”.

Rockefeller saw that his name and reputation were driving much of the negative coverage. Members of the International Workers of the World had picketed the entry to his Westchester County, New York, estate. Muckraking novelist Upton Sinclair led a protest at Rockefeller’s Manhattan offices. The tycoon began working on his image. In September 1915, his staff arranged for him to visit southern Colorado where he called on miners at home and talked with them. Miners’ families wanted to meet him. At a company town school, students sang to him and when the band struck up a waltz Rockefeller danced with miners’ wives. Colorado Fuel and Iron disbanded its guard force, allowed miners to elect check-weight men, and established a company union for addressing grievances.

“I believe Mr. Rockefeller is sincere. I believe he is honestly trying to improve conditions among the men in the mines,” John Lawson said, tempering his remarks with criticism. “Rockefeller has missed the fundamental trouble in the coal camps,” Lawson said. “Democracy has never existed among the men who toil under the ground—the coal companies have stamped it out. Now Mr. Rockefeller is … is trying to substitute paternalism for it.”

Not until 1933 did Colorado Fuel and Iron sign a UMWA contract.

In 1918, the UMW memorialized the five miners, two mothers, and 11 children who died in what has come to be known as the Ludlow Massacre. The statue adjoins the pit in which the women’s and children’s bodies were found. In 2009 the National Park Service declared the site a National Historic Monument. In an ongoing University of Colorado project, anthropologists are unearthing and analyzing artifacts from the massacre site. Objects found at the barren site include teacups, canning jars, iron bed frames and ruined musical instruments.

Betsy Harvey Kraft (“Bloody Ludlow”) is the author of “Mother Jones, One Woman’s Fight for Labor; Sensational Trials of the Twentieth Century”; “Theodore Roosevelt: Champion of the American Spirit”; and other books for young adult readers. She was an editor at E.P Dutton and Macmillan in New York and lives in Washington, D.C.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.