Facts, information and articles about The Black Hawk War, an event of Westward Expansion from the Wild West

The Black Hawk War Facts

Dates

May-August 1832

Location

Michigan and Illinois Territory

Commanders

Black Hawk: Neapope, Wabokieshiek,

Settlers: Henry Atkinson, Henry Dodge, Isaiah Stillman

Soldiers Engaged

6,000 militiamen, 630 Army regulars, 700+Native Americans VS. 500 warriors and 600 non-combatants.

Casualties

77 killed on the settler’s side and 450-600 killed on the Native American side

Result

Unites States Victory

Black Hawk War Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about The Black Hawk War

» See all Black Hawk War Articles

The Black Hawk War summary: The brief conflict that was fought in 1832 was given the name the Black Hawk War and was between the United States and Native Americans. It was led on the Native American side by the Sauk leader Black Hawk. The trigger point for the war was when Black Hawk and warriors from the Kickapoos, Meskwakis and Sauks crossed the Mississippi River into the territory of Illinois. Though Black Hawk’s motives were mysterious his intent was to recapture the land that the US had claimed in the 1804 treaty without bloodshed.

Black Hawk’s group was known as the British Band and American officials believed them to be hostile therefore gathered their frontier army. The frontier army was comprised of militiamen that were poorly trained, part-time American troops, and a few U.S. Army soldiers. They open fired on British Band on May 14, 1832 and the group responded by attacking back. The Battle of Stillman’s Run was where the attack was staged and Black Hawk’s band gave the US Army a sound beating.

It spread over land and several battles. They army commanded by General Henry Atkinson caught up with the British Band in July and beat them at the Battle of Wisconsin Heights. Members of Black Hawk’s group retreated back toward Mississippi. The Battle of Bad Axe was where the American soldiers caught back up with them on August 2nd and killed or captured most of them. Black Hawk along with a few other leaders escaped to later surrender and suffer imprisonment for a year.

Featured Article About The Black Hawk War From History Net Magazines

Black Hawk War

The militia surgeon was terrified. All around him the night flickered and danced with muzzle flashes, and the darkness rang with terrifying war whoops and screams of terror. Desperately he kneed his rearing horse, but could not pull away from the grim, dark form holding tightly to his mount. He leaned forward into the gloom and held out his sword.

‘Please, Mr. Indian,’ he pleaded, ‘I surrender. Please accept my sword.’

Only after his captor failed to take the sword, or move at all, did the petrified doctor realize that he was talking to a stump, one to which he had tied his horse. Slashing the tether, the surgeon fled madly into the night.

For 25 miles, he and hundreds of his militia comrades galloped through brush and trees, crazy with fear, more than a little drunk, and certain that every bush and log was a Sauk warrior with a tomahawk thirsting for white man’s blood. Few of them ever actually saw an Indian or fired at anything other than shadows.

These Illinois militiamen had been spooked by a couple of dozen Sauk warriors, who were as surprised as anybody at the panicked rout. The militia officers, with few exceptions, were in the van of the retreat, led by a colonel named Strode, notable, until then, chiefly for a large mouth and a bellicose air.

Thus the Battle of Old Man’s Creek, ever after to bear the unfelicitous name of Stillman’s Run, was appropriately christened for the overall commander of the frightened rabble, Cavalry Major Isaiah Stillman. The defeat was more humiliating than serious: only 12 militiamen had been killed, although a good many more had deserted for good. The Sauk had lost three braves, one a prisoner murdered as the fight began.

Later, there would be a good deal of pious bragging and invention about a gallant defense against hundreds of Indians. But the militia knew it had been whipped, whipped badly and nearly frightened to death. In later days, most of the men didn’t talk a lot about being at Stillman’s Run. One officer spoke for most of them in a letter to his wife: ‘I will make you one promise, I will stay with you in future, for this thing of being a soldier is not so comfortable as it might be.’

Indeed it wasn’t. What had started as a wonderful, drunken Indian-killing party was getting serious and, what was worse, downright dangerous. But the war would go on. It was mid May of 1832, and a fundamental question still had to be decided that spring. Was the Sauk and Fox nation to be allowed to return to its ancestral lands near Rock Island, east of the Mississippi, or was it to be forever confined to its new home west of that river, to which it had been exiled by a scandalous treaty signed in 1804?

The Indian signatories to the treaty had had no authority to speak for the entire tribe. Only one was a legitimate chief, and even he was a noted alcoholic. The Indians’ compensation was pitiful; one historian called it a collection of ‘wet groceries and gewgaws.’ As young West Pointer George McCall put it, the fact that the white men had simply stolen the Sauks’ land ‘was apparent to the most obtuse.’

Even this farcical treaty had given the Sauk and Fox the right to hunt and plant on their old ground until the land was surveyed and opened for settlement. But hordes of settlers had promptly squatted on the land, making the treaty unenforceable. It was too much for proud men to bear.

And so, in the spring of 1831, a band of Sauk crossed the Mississippi and moved into the ancient tribal territories around Rock Island. Their hearts were there, and so was their chief village, a well-laid-out town called Saukenuk. The Indian invasion produced a small amount of bloodshed–and unmitigated panic on the part of the squatters, who promptly appealed to the government for help.

Major General Edmund Gaines, Western Department commander, sent the 6th United States Infantry and part of the 3rd, and asked the Illinois governor for added militia assistance. War was averted when still another treaty was thrashed out with the Sauk, who promised never again to cross to the east bank of the Mississippi without the consent of both the U.S. president and the governor of Illinois.

Within four months, however, a Sauk band was back across the river, and was said to have killed a couple of dozen Menominee Indians, their hereditary enemies. The panic stricken squatters again appealed for government aid. It was, after all, less than 20 years since the frontier horrors of the War of 1812, when most of the northwestern Indians had joined the British. Many Indians still fondly remembered those days, the times of victory over the Americans. One of them spoke for all: ‘I had not discovered one good trait in the character of the Americans. They made fair promises, but never fulfilled them! Whilst the British made but few–but we could always rely upon their word!’

The man who spoke those words was 67 now, but still a power among the Sauk. He was not a great chief, but a war leader, a general who had killed his first man when he was 15. He was also a consummate tactician. His name was Black Hawk.

On April 8, 1832, some 300 regulars of the 6th Infantry left Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis, by boat. They moved smoothly upriver in the burgeoning spring, under the command of bumbling Brig. Gen. Henry Atkinson, and arrived at Rock Island on the 8th. There they found that Black Hawk’s band–called ‘the British Band’ for their undying allegiance to their old friends–with some local Sauk and some Kickapoo had moved up the Rock River. There were said to be 600 to 800 well-armed braves, more than half of them mounted. And, because they intended to reoccupy their old lands, many of them had brought their families with them.

Atkinson sensibly decided he needed cavalry to catch a mounted enemy. The regular army had no mounted troops because a cheese-paring Congress would not appropriate money for them. Infantrymen were cheaper, and dollars were far more important on Capitol Hill than military preparedness. Any mounted men would have to come from the local militia, and Atkinson asked Illinois Governor John Reynolds for help.

Reynolds, a pompous bumpkin, jumped at the chance. ‘Generally speaking,’ as one historian neatly put it, ‘history has been kind to the governor by not mentioning him at all.’ Reynolds, an intellectual pygmy, was nevertheless alert to the political advantage to be gained from taking the offensive against the Indians–any Indians. Based on some early and undistinguished service in the War of 1812, Reynolds had conferred upon himself the sobriquet of ‘the Old Ranger.’ Now he would add to his self-developed luster by personally leading the militia to chastise the heathen.

Militia had long been the bane of the regular army. Although they had fought well at times. they had also done a shameful amount of running away. ‘Mad Anthony’ Wayne, who knew something about soldiering, thought he would do well to get two volleys out of the militia before they fled the battlefield. It was not so long since the Bladensburg Races, that dismal day outside Washington when a whole army of militia had skedaddled before a thin line of British bayonets and the whooshing of wildly inaccurate Congreve rockets.

The ensuing war would bring nobody glory, except maybe the Indians. A rawboned captain of militia named Abraham Lincoln would seldom mention his participation except to comment drolly on the size of the mosquitoes that preyed on him and his men. Other participants–especially officers of the regular army–bluntly called the campaign what it was.

‘A tissue of blunders, miserably managed,’ said Zachary Taylor, destined for well-deserved fame in the Mexican War and, ultimately, the White House. One of his junior officers, Albert Sidney Johnston, agreed. ‘An affair of fatigue, filth,’ he wrote, ‘petty jealousy, bickering [and] boredom.’

The militia showed up at Rock Island in droves, a couple of thousand of them by early May. These uncouth Illinois men rejoiced in the local nickname of ‘Suckers,’ in memory of one of their chief foods, the unlovely bottom-feeding fish of the same name. The men were furnished food, equipment and arms by the government, and produced prodigious quantities of both hot air and whiskey, without which no movement apparently could be attempted.

The Suckers poked fun at the regular troops they saw, in part because the regulars had to walk. The militia could ride in some comfort, and pursue its Indian quarry with much greater dispatch. As it turned out, it could also run away from a fight, a thing it was to do often. Militiamen would kill many horses during the campaign, galloping madly away from danger, real or imagined. Most of them would kill nothing else.

Still, the militiamen were loud and boastful, singularly dedicated to their constant companion John Barleycorn and wholly without discipline. The only response to Lincoln’s first command was the loud advice to ‘go to hell!’ Apparently, the future president’s experience was not unusual. Part of this chronic indiscipline was frontier orneriness; part of it, maybe most, was whiskey. One soldier wrote of hearing officers shouting at their men: ‘Fall in, men–fall in! Gentlemen, will you please come away from that damned whiskey barrel!’

The regulars, in turn, were not pleased with their new allies. They rightly considered them buffoons, ill- disciplined, noisy, and all too likely to run away. For their part, the militia made fun of the regulars, calling them ‘hot-house lettuces,’ given to taking tea with the ladies and ‘eating yellow-legged chickens,’ an apparently pejorative frontier term that loses something in modern translation.

Reynolds, militia had its chance almost immediately, and the result was the absurd debacle at Stillman’s Run on May 14. The evening before, the Suckers had decided to abandon their supply wagons, and each man took what he needed–especially whiskey. ‘Everybody offered everybody a drink,’ said one participant, and the column straggled on toward Old Man’s Creek. By sundown the Sucker horde was ‘corned pretty heavily.’

As evening began to come down, a handful of foraging Indians was spotted ahead, and a mob of militia galloped off in pursuit. Taking three prisoners along the way, they killed two more fleeing Sauk. Their dashing pursuit ended abruptly, however, when they ran head-on into Black Hawk and 40 braves, all he could collect of the scattered tribe. These 40 were angry and aggressive, not at all what the Suckers were used to, and the militia galloped back toward their camp as fast as they had come.

Bedlam followed. The militia had enlisted only for 30 days, and as the fourth week approached they could think of all kinds of reasons why they had to go home. Some simply deserted. There was no end to the accusations about who was responsible for the shame of Stillman’s Run, and the governor seemed to have lost what little control he had. The regulars were so contemptuous of the militia that Atkinson put the Rock River between his men and the Suckers to avoid collision.

Atkinson did what he could to get the expedition going again. He got a scouting party out, led by a scruffy, hard drinking son of Alexander Hamilton called Uncle Billy. Before anything more could be done, word came of the massacre of 15 white settlers on Indian Creek and the kidnapping of two teen-age girls by the raiders.

Frightful news of other killings and burnings caused mass flight along the frontier, with fugitives pouring into havens as far away as Chicago. Not all the raiders were Sauk; there were Winnebago, too, but winged rumor made no distinction. At one settlement two shots fired at a flock of wild turkeys were enough to stampede everybody in the entire area into a wild flight for shelter in the local fort.

Meanwhile, orators and newspapers all along the frontier screamed for bloody revenge. By the end of May, much of the Sucker militia had disbanded, only 250 men heeding frantic appeals from the Old Ranger to re-enlist. There was a new levy coming, but nobody knew just how large it would be. Men were unenthusiastic about the war. The Detroit Free Press sneered, ‘There is no danger–no more probability of an invasion by Black Hawk’s party than there is from the Emperor of Rusia [sic].’

A new swarm of militia soon gathered, however, thirsting for Indian blood and stealing anything that was not nailed down. They were organized into three brigades of about 1,000 men each, still as loud, brawling, hard- drinking and undisciplined as ever.

Black Hawk, camped around Lake Koshkonong, learned of the new army and knew he could not wait for it to come looking for him. In mid-June, he went over to the attack. First he sent small parties on forays westward, a feint to convince his enemies that he was beginning to move into Iowa. Meanwhile, his main force remained around Koshkonong, hunting to support the families.

The raiders stole stock and struck at isolated parties of whites, leaving a trail of scalped, mutilated bodies and unmitigated terror. The white pursuers did win one small success at a place called Pecatonica Creek. It wasn’t much of a fight: 20-odd militia took on 11 Kickapoo and managed to exterminate them while losing three of their own.

The frontier went crazy with delight. An ocean of hyperbole elevated the little skirmish into something approaching the Battle of Waterloo, and the leader of the militia was proposed as a candidate for governor. ‘The annals of border warfare,’ crowed one writer, ‘furnish no parallel to this battle.’ That much was true: never in the field of frontier conflict had so much been said about so little.

In fact, the Battle of the Pecatonica did nothing to stop the ceaseless strikes of Black Hawk’s war parties, and most of the settlers remained terrified, disorganized and feckless. The besieged fort at Apple River was saved only by the exertions of a tough, tobacco-chewing woman, appropriately named Armstrong. This profane Fury tongue-whipped the terrified refugees inside the fort and bullied the male defenders into action, dragging one man from his hiding place inside a barrel and shoving him to a loophole.

But now there were too many regulars and militia, and Black Hawk’s time was running out. Gradually the white juggernaut moved ahead, pushing up the Rock River past Lake Koshonong. Black Hawk’s band, with its women and children, fell back. It was not easy for either pursuers or pursued. On went the chase, slogging through a dreadful region called the ‘trembling lands,’ a maze of swamp and bog and hummock, waist-deep in stinking water.

By mid-July, the whites were desperately short of supplies, and the ponderous pursuit halted, still without visible success. A number of militiamen were sent home, doubtless to Atkinson’s relief, and the governor seized the chance to go home with them, loudly assuring everybody that Black Hawk was finished. Among those mustered out was Abraham Lincoln, on his way home to infinitely greater things.

If Atkinson was to have the glory of winning this war, he would have to move fast. President Andrew Jackson, never a patient man, had already tired of the glacial pace of the campaign, and had sent out someone he knew would do something about it. General Winfield Scott, a smart, driving regular officer destined for glory in the coming war against Mexico, was sent west to take command.

Atkinson pulled his diminished force together and slogged on after Black Hawk, who was plainly heading back toward the Mississippi. It was a miserable march, dragging its way through more of the ‘trembling lands,’ plagued by torrents of rain, blown-down tents, and a stampede that left many militiamen on foot. On July 20, the column’s leading elements cut Black Hawk’s trail. The effect on Atkinson’s tired army was electric. Morale rose and the men pushed on hard, living on raw bacon and wet cornmeal, snatching sleep on the ground under the pouring rain.

It was the beginning of the end. Black Hawk’s band was already in dreadful straits, reduced to eating roots and treebark to stay alive, and leaving behind the bodies of old people dead of starvation. The militia was closing faster now as they broke out of the swamps into open country, near Madison, Wis.

Just when it seemed the war was over, Black Hawk turned on his pursuers at a place called Wisconsin Heights. Vastly outnumbered, he would not close, but volleyed again and again with musket fire, keeping the whites off-balance and on the defensive as militia casualties mounted. At last, as night began to fall, the Suckers managed a bayonet charge toward the high ground and the ravine from which the Indians’ galling fire had come. The attack struck empty air–Black Hawk was gone.

The whites, nevertheless, congratulated themselves. ‘Our men stood firmly,’ one wrote proudly, unaware that’standing firmly’ was precisely what Black Hawk wanted the army to do. While they stood firmly, he had gotten his whole band across the Wisconsin by canoe, losing only six braves. He had commanded about 50 Sauk ‘barely able to stand up due to hunger.’

Now it was a race. Some of Black Hawk’s exhausted band kept on down the Wisconsin. Others headed for the confluence of the Bad Axe River and the Mississippi, north of Prairie du Chien. There, the Mississippi broke into shoals and islands, and it might be possible to cross to the west. Black Hawk could not know that a thoughtful regular officer had already anchored in the mouth of the Wisconsin with a flatboat, manned by 25 regulars and a six-pound cannon.

The pursuers pushed ever closer to the Sauk band, slogging through trackless swamp, matted undergrowth and difficult hills. Now, the leading Sucker units knew they were close: the air was filled with circling buzzards and the way was littered with Indian corpses. A few were marked with wounds, but most of them had simply died of exhaustion and starvation.

It was all over now but for the killing. At the Wisconsin’s mouth, one band of Sauk was stopped cold by the flatboat’s murderous short-range grapeshot. The survivors scattered to the river’s banks. They would perish miserably over the next few days, hunted down and killed by bands of Menominee led by Alexander Hamilton’s shabby son.

Across the broad Mississippi waited bands of Sioux, alerted that the hated Sauk would try to cross. And upstream, as Black Hawk’s miserable survivors reached the mouth of the Bad Axe, blasts of canister from the steamboat Warrior slashed through them and drove them back from the shore. The remaining Sauk were hemmed in between the great river and Atkinson’s force, outnumbered 4-to-1.

The whole ugly affair ended on August 2, as Black Hawk knew it must. Atkinson’s men dropped their packs, fixed bayonets, and pushed toward the banks of the Mississippi, regulars in the center, militia on either flank. There were perhaps 1,100 of them, plodding in line, holding muskets and equipment over their heads as they waded through pools of stagnant water. They pushed cautiously into the thick morning mist along the river.

Black Hawk’s warriors got off a single volley, and then the white army closed. They took a mere 27 casualties–only five of these dead–and Black Hawk’s band was simply destroyed. At least 150 bodies were found, including many women and children. Many fell or jumped into the river, and the Mississippi took them forever. Those few who escaped were hunted down by vengeful Sioux and Winnebago, and even some quisling Sauk.

A few fugitives took to the water and the islands in a vain attempt to escape across the river. Fire from the Warrior killed many of these with grapeshot and musketry, and even crushed some of the survivors with her paddle wheel as they tried to hide in shallow water. Fortified by whiskey, some militiamen pushed on to the islands, and more miserable fugitives were killed there.

A few of Black Hawk’s people escaped, against all odds. Many squaws tried to swim, some carrying small children on their backs. A few made it. Most sank under a hail of musketry, or were taken by the river as their strength ebbed. One mother swam the great river holding her tiny baby by clutching the child’s neck in her teeth. She would survive and so would the child, who rose to be a chief, ever after called ‘Scar Neck.’

Perhaps 115 of Black Hawk’s band remained as prisoners, nearly all of them women and children. It was over, and there was much celebration and whiskey drinking and boasting over the pitiful scalps and booty that were all that remained of the British Band.

If the fighting was over, the dying was not. Cholera stalked down the river with the remains of Scott’s force and struck mercilessly at Sucker and regular alike. Fifty-six men were dead within a week, and many others deserted in terror, further spreading the epidemic. Its hideous rictus and vomiting would claim victims for the rest of that year and into the next, spreading all the way down the river to New Orleans, where it would kill 500 a day at its height.

But at least there would be peace, however shameful. A new treaty was dictated by the victors. By its terms, the Sauk would leave the east bank of the Mississippi forever and give up a 50-mile strip on the west bank as well. There would be a trumpery payment to the tribe, which worked out at about $4 per Sauk per year, before, of course, ‘deductions’ for various sums owed merchants and agents.

Black Hawk was not among the prisoners, nor was his body found among the dead. He had left before the battle, old and tired and sick at heart. Whether he had simply given up on the war or was trying to lead part of Atkinson’s troops away from the Indian families is not clear. In any case, his people did not blame him for his absence. He had led them well. The long march was over. Black Hawk had lost.

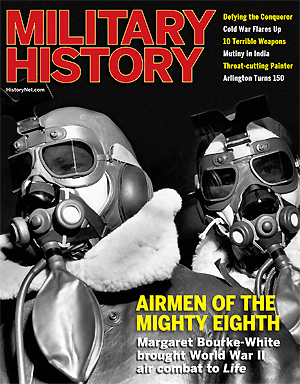

This article was written by Robert B. Smith and originally published in the February 1998 issue of Military History magazine.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Military History magazine today!