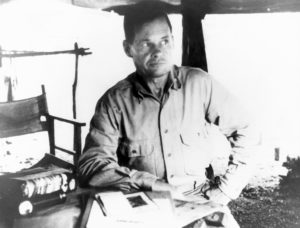

The fortunes of war had already swung back and forth several times between American and Japanese forces on Guadalcanal by late October 1942. The greatest danger point for the United States up to that time had come during the Battle of Edson’s Ridge on September 11-13, when a depleted battalion of Marine Raiders reinforced by a handful of parachutists had stemmed a fierce assault by the Kawaguchi Brigade. The last major Japanese effort, and the only other counterattack that had a real chance of recapturing Henderson Field from the 1st Marine Division, began on October 24. On the first night of that battle, only a single battalion stood between the Japanese Sendai Division and the vital airstrip. Luckily for the Americans, the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines (1/7), was commanded by one of the toughest and most determined leaders in the Corps–Lieutenant Colonel Lewis B. Puller. Nicknamed ‘Chesty’ for his barrel torso, bulldog demeanor and readiness to speak his mind, he would more than earn his third of five Navy Crosses for his steadfast leadership during the fighting that would soon be christened the Battle for Henderson Field.

Puller and his battalion had arrived on Guadalcanal with the rest of the 7th Marine Regiment on September 18. Although Chesty had trained his men well, the green unit did not get off to an auspicious start. The first night ashore, Japanese ships inflicted several casualties when they bombarded the coconut grove in which the regiment had bivouacked. During a battalion-size patrol over the next two days, Puller lost a few more men and was incensed when his battalion joined in unprovoked nighttime shooting with other men of the regiment. At the Second Battle of the Matanikau later that month, the Japanese thwarted 1st Marine Division commander Maj. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift’s effort to gain control of the Matanikau River. In the process, a good portion of the 1/7 (under the command of Puller’s executive officer) was trapped for a time behind enemy lines. Only Chesty’s daring efforts in commandeering a destroyer and supervising an amphibious withdrawal under fire saved the force from annihilation. Having suffered more than 10 percent casualties (including the battalion executive officer and all three company commanders) at the end of 10 days on the island, the morale of the 1/7 was at a low ebb.

Division gave Puller’s battalion no time to contemplate the results of the battle. On September 28, Vandegrift issued orders for the 1/7 to move up and replace Lt. Col. Herman Hanneken’s 2/7 on the perimeter. The assigned zone was south of Henderson Field in jungle flatlands. On the right flank was the 3/7, occupying Edson’s Ridge. On the left was the 1st Marines sector, which looked out over a field of kunai grass and then curved north till it reached the coast. The new home of the 1/7 had been largely unoccupied until the arrival of the 7th Marines, and Hanneken’s men had been building defensive works there for the past week. Chesty immediately directed his Marines to improve upon what they found.

The troops carved out the undergrowth to create wide, interlocking fire lanes for their machine guns and anti-tank guns, which they placed in bunkers covered by logs and sandbags. They strung double-apron barbed-wire fences and attached ration cans containing pebbles to prevent intruders from silently cutting through the barriers. The riflemen’s deep fighting holes stretched along the entire sector; many of them sported overhead cover as work progressed. Roughly 100 yards to the rear, the men hacked out a path paralleling the front line, so they could move from flank to flank without being observed by the enemy. In the west, this narrow lane tied in with the dirt road snaking down from Edson’s Ridge and leading back to the airstrip. In the opposite direction it connected with a similar communications trail in the 1st Marines’ zone. About 50 yards farther back from the trail, near the left end of the line, was a log- and sandbag-covered bunker housing Puller’s command post. Each day, while two-thirds of the battalion dug and cut and built, a company-size patrol penetrated the jungle in search of signs of the Japanese.

With the passage of time and the establishment of some semblance of routine, the officers and men of the 7th Marines began to adjust to their surroundings. According to one member of the regiment, they found Guadalcanal ‘hotter, more mountainous, more rugged, wilder’ than Samoa, but they were growing used to the’strange jungle noises’ that permeated the night. Mosquitoes and midnight nuisance raids by enemy aircraft, however, continued to rob everyone of precious sleep. Food remained in short supply despite the stores brought in by the regiment. Even with the supplement of captured Japanese rations, there were just two meals a day. One officer noted in his diary: ‘Everybody more than hungry. The men can’t seem to get enough to eat.’ Water also was hard to obtain, since it had to be lugged in 5-gallon cans hundreds of yards from the nearest river. The 7th Marines soon began to look like the other veterans of the campaign, gradually acquiring the rail-thin appearance of the undernourished and the hollow-eyed visage of the exhausted.

During this lull, Puller tried to maintain the mental and physical well-being of his force. He had the companies dig wells and then ordered the men to start shaving. Doctor Edward L. Smith, the 1/7’s surgeon, also noted his commander’s emphasis on the spiritual: ‘Not an outwardly religious man himself, he encouraged divine services to be held frequently up on the front lines for the men who wanted them. Puller would much sooner have given services himself than not to have any. On several occasions he was dissatisfied with a chaplain’s talk, and he grumbled to me that maybe it was time he tried his hand.’ Smith noticed, as well, that ‘it was the colonel’s wish always to keep the men well informed with whatever news there was.’ Every day Puller moved among the growing defensive works and stopped to chat with the troops. An officer noticed that ‘the boys are beginning to feel better.’

While the division strengthened its defenses in early October, patrols from the 5th Marines revealed a continuing buildup of Japanese forces west of the Matanikau River. Vandegrift launched the 1/7 and several other battalions in a much larger version of the late-September operation that had gone awry. Puller’s outfit played a significant role in the renewed action, this time handily defeating an enemy battalion and nearly wiping it out. The tables had turned decidedly in favor of Chesty and the rest of the division.

The Third Battle of the Matanikau was only the prelude to a rapid-fire series of major actions in the seesaw campaign for Guadalcanal. Off Cape Esperance on the night of October 11-12, an American fleet defeated an enemy naval force escorting a reinforcement convoy to the island. The victory was not complete, however; the Japanese landed four large-caliber artillery pieces to shell Henderson Field. In addition to manning the main defensive lines, the division would occupy a position astride the Matanikau to keep Japanese guns out of range. The key to this scheme was the arrival of a U.S. convoy on the morning of October 13. It disgorged the Army’s 164th Infantry Regiment, a North Dakota National Guard outfit with a proud heritage from previous wars. With that added manpower, Vandegrift could afford to establish a two-battalion, horseshoe-shaped outpost along the Matanikau.

As part of the reshuffling of forces, the 3/7 would head out to the new position in the west, the 1/7 would go into reserve near the main airstrip and the 2/7 would take over responsibility for the entire 7th Marines sector. Chesty’s Marines knew their new location would put them into the Henderson ‘V ring’–the center of the bull’s-eye for Japanese air and naval bombardments. What no one foresaw was the vast increase in the scale of enemy attacks. Puller’s battalion luckily avoided the worst of it. During his men’s last night in the front lines on October 13-14, Japanese battleships Kongo and Haruna pounded the main field and the recently opened auxiliary fighter strip with nearly a thousand 14-inch shells. For the balance of the night Japanese planes harassed the perimeter. The deluge of steel put much of the so-called Cactus Air Force out of commission, destroyed nearly the entire stockpile of aviation gas and killed 41 men.

Large-scale air raids and the first shells from the enemy’s 150mm guns added to the devastation the next day, though measures had been taken to disable the guns. Puller’s outfit threaded its way down to the airfield between attacks and went into reserve. That night two cruisers fired more than 750 8-inch shells into the perimeter, one of which killed a 1/7 Marine. The following evening another task force hit American positions with nearly 1,300 5- and 8-inch rounds. An intelligence man in Chesty’s command post recalled the battleship bombardment as ‘the most terrifying night of [his] life.’ Captain Charles Kelly, the battalion executive officer, spent the night in the dugout with Puller and afterward said ‘there is nothing more demoralizing than naval gunfire–you can hear each round leave the ship and come in like a freight train.’ A sergeant in the 1/7 recorded in his diary: ‘I shook and trembled all through the first night, more afraid [for] my life than I’ve ever been before.’

Through herculean efforts, the Cactus Air Force managed to get some planes aloft to attack a six-ship convoy unloading troops and supplies on October 15. American fliers were able to destroy three of the transports, but not until most of their contents were deposited on the beaches west of the perimeter. The reinforcements included about 4,500 men and more 150mm howitzers. The routine runs of the nightly ‘Tokyo Express’ during October added another 9,000 troops and additional supplies to those totals. With this fresh manpower and materiel, Japanese leaders planned a new offensive that would dwarf their previous efforts to retake the airfield. Their scheme called for a two-pronged diversionary attack along the Matanikau. A tank company and two infantry battalions would strike across the river mouth, while three infantry battalions moved to turn the inland flank of the 3/7. Those twin assaults would be coordinated with the main thrust by Lt. Gen. Masao Maruyama’s Sendai Division, which would hit the southern side of the Marine perimeter. Despite the experience of the Kawaguchi Brigade at Edson’s Ridge, the Japanese were certain that the southern sector was undefended. They conducted no reconnaissance to verify that assumption. The scheduled date for the three attacks was October 22.

Before the Sendai set out toward Edson’s Ridge, Maruyama apprised his officers and men of the stakes: ‘This is the decisive battle between Japan and the United States in which the rise or fall of the Japanese Empire will be decided. If we do not succeed in the occupation of these islands, no one should expect to return alive to Japan. [We] must overcome the hardship caused by the lack of material and push on unendingly by displaying invincible teamwork. Hit the proud enemy with an iron fist so he will not be able to rise again.’

The lead elements of the division began their approach march over a hilly, narrow jungle trail on the 16th. In addition to normal loads, each soldier carried extra food plus an artillery shell for the mountain guns being manhandled in pieces over the rough terrain. Despite their general’s exhortation, the mood of the Sendai was downcast. The troops were limited to a half ration or less per day; often they could not even cook their rice. The hungry men only grew weaker as they fought up and down steep ravines and endured sleepless nights amid the tropical rains. One lieutenant recorded in his diary, ‘Many soldiers fear the enemy gunfire, and the morale of the soldiers is very poor.’

On October 20, the 1/7 moved back into the lines, reassuming responsibility for the left half of the 7th Marines sector, while the 2/7 contracted into the right half. The men went to work again improving their defenses, which Puller considered only 30 percent complete. Despite his low estimate, it was a formidable position. In addition to the fire lanes, barbed wire, bunkers and fighting holes, both battalions were generously equipped with heavy weapons. Each had its normal complement of mortars (six 60mms and four 81mms) and .30-caliber machine guns (24 heavy and six light). Infantry battalions also rated a pair of .50-caliber machine guns. The regiment had three anti-air, anti-tank platoons, each with five .30-caliber and two .50-caliber machine guns and four 37mm anti-tank guns. The 7th Marines had emplaced all of those platoons in the front lines of its sector in September and kept them there throughout the movements of the battalions. Enterprising members of the regiment may also have scrounged some extra machine guns from wrecked aircraft or other sources. As a result, the defenses bristled with automatic weapons and direct-fire cannons. In terms of manpower, the 1/7 was in good shape by Guadalcanal standards, with 80 percent of its authorized strength on hand and reasonably fit for duty. (Malaria, the worst threat to health on the island, had a relatively slow gestation period, so few men in the 7th were affected at this time.) One officer in the battalion believed that ‘not since WWI had there been such a picture-perfect example of a fixed military defensive position.’ Vandegrift described it as ‘a machine gunner’s paradise.’ The division commander asserted, ‘I feel confident that if we can have fifty to one hundred yards of cleared space in front of us, well wired, mined, and booby-trapped, that our fire and grenades will stop any assault they can make.’

On the 21st, Colonel Amor L. Sims, commanding officer of the 7th, told Puller to place a platoon-size observation post (OP) on a knoll 1,500 yards south of the left flank of his lines. Chesty and his operations officer, Captain Charles J. Beasley, were not happy with the order. In the event of a major attack, they assumed the small OP would be overwhelmed. Nevertheless, Puller sent a platoon to the site and thereafter replaced it with a fresh group each day. The outpost held terrain that dominated a large, flat grassy area. The open field was a few hundred yards wide and stretched south for about 2,000 yards from the very left front of the 1/7’s position. The 164th Infantry, which now held the sector to Chesty’s left, aptly nicknamed this narrow plain the ‘Bowling Alley.’

The regiment continued to run daily patrols, but now it was using several squad-size elements rather than a single company. They uncovered a few small signs of the enemy. Those bits of information notwithstanding, Vandegrift and his staff were convinced even on October 23 that ‘all signs point to a strong and concerted attack from the west.’ Division decided to reorganize its forces and place troops from a single regiment in the Matanikau OP. Marine leaders were finally learning from earlier difficulties along that river–they wanted to fight the next battle with a cohesive unit operating under its normal commander. The 7th Marines drew the assignment, but the reshuffling of forces required a juggling act to keep every mission covered. The 164th Infantry would continue to hold the eastern flank of the perimeter, with its right tying in to the 7th Marines sector in the south. The 1st and 5th Marines remained responsible for the areas southwest and west of the Lunga River. Both the 164th and the 5th had a battalion in regimental reserve, while the 3/2 served as the division reserve. Vandegrift elected to send Sims and the 2/7 west on October 24, where they would join the 3/7 in the Matanikau OP and relieve the 3/1 for reassignment to Hanneken’s former position. While that swap was underway, the 1/7 would defend the entire southern sector by itself, supported only by a rump regimental command post under Lt. Col. Julian Frisbie, the 7th’s executive officer. It was a calculated risk, but Division was confident there was no immediate threat to that zone. The chief of staff, Colonel Gerald C. Thomas, actually thought it would be an opportunity for Chesty’s battalion to avoid another battle and rest up after ‘two pretty rough shows.’

Upon receipt of the change in plans, Puller and his executive officer conferred and decided it would be too complicated to shift the entire battalion to spread it over the 2,500 yards of frontage. They also figured that the high ground of Edson’s Ridge presented a more defensible position. So Kelly would take one platoon from each rifle company, plus a slice of the weapons company and the battalion command post, and occupy the 2/7’s old position (where half of the regiment’s heavy weapons remained in place). Puller also sent the majority of his headquarters personnel up to bolster the line. The battalion settled into the new arrangement on the afternoon of the 24th. From left to right, it was Able, Charlie and Baker companies and Kelly’s provisional outfit. That tactical layout had one grave weakness–there was no reserve–but Puller could do nothing else, given the small number of troops at his disposal.

Captain Regan Fuller was especially uneasy about his part in the setup. His Company A had only one rifle platoon in its’sadly undermanned’ zone, since one was with the battalion executive officer and the other was at the OP for the night. Adding to the captain’s concern, a jeep trail led out from his position to the grassy field. But Battalion had this likely avenue of approach into the Marine lines covered with at least four heavy machine guns, two 37mm cannons and preregistered mortar targets. It was, remembered one Marine, ‘an awesome concentration of coordinated fire.’

The Japanese were also making their final deployments. The diversionary force continued its successful efforts to deceive the Americans, with artillery fire on October 18 and a probe by tanks on the 20th. The main force, however, was falling behind schedule as it struggled over the forbidding terrain south of Henderson Field. On the 21st, Maruyama received permission to delay the attack of his Sendai Division until the night of October 23. But things only grew worse as time passed. The plan called for an assault by two regiments, with the 29th Infantry striking at Edson’s Ridge and the 230th Infantry punching through just to the east. The 16th Infantry would follow up in reserve. During the day on October 23, the commander of the right wing argued for a shift farther to the east and moved his force in that direction. Maruyama promptly relieved his unruly subordinate. The general also discovered he was not as close to the Marine lines as he had thought, and his units were becoming disorganized as they spread out into attack formation and pushed through the dense vegetation. Again he sought and was granted a one-day delay. That word did not reach the diversionary force, which launched a tank assault across the mouth of the Matanikau on the evening of the 23rd. Marine anti-tank guns destroyed the armor; artillery killed hundreds of infantrymen in assembly areas on the west bank. The cost to the Americans was 13 dead and wounded. The other wing of the diversionary force did not attack–it also had failed to reach its jump-off point on time.

The next day, the Sendai Division prepared for its assault, now scheduled for 1900 hours. Late that afternoon, as the two lead regiments moved toward Marine lines, torrential rain began to fall. A Japanese admiral out at sea considered it ‘a heaven-sent phenomenon’ that would mask the final approach of his army colleagues. Maruyama and his men were not so ecstatic. The combination of slippery footing and thick foliage, plus the onset of absolute darkness, slowed and confused the deployment of forces. In a repeat of earlier mistakes by the Kawaguchi Brigade, the Sendai had also failed to reconnoiter and mark approach lanes leading to the American perimeter. As a result, the right wing veered off to the northeast over the course of the evening. It would end up largely missing the Marine defenses. The left wing drifted eastward as well; instead of making contact at Edson’s Ridge, it headed toward the center and left of the 1/7’s position.

As the Japanese floundered forward, their presence finally came to the full attention of the defenders. Around 1600, native scouts entered the right flank of the 164th Infantry sector and reported that they had observed about 2,000 enemy soldiers not far from the lines. A Marine scout-sniper also arrived at Division with news that he had earlier observed what appeared to be ‘the smoke of many rice fires’ to the south. The final confirmation came around 2100, when Platoon Sergeant Ralph M. Briggs, commander of the 1/7 OP, telephoned the command post that he could hear large numbers of enemy soldiers moving past the knoll. The platoon was ordered to stay put until the Japanese were clear of the area; after that, Briggs could attempt to move his men across the Bowling Alley and out of the line of fire. Puller passed the word to hold fire until the last possible moment. That would give the men in the OP time to escape and would maximize the effect of Marine heavy weapons.

This was not the only threat that evening. During the morning, Marines in the 3/7 had briefly observed the second wing of the diversionary force moving toward the left, or southern, flank of their position along the Matanikau. The battalion immediately began working over the likely routes of approach with airstrikes and artillery. Division command also changed the mission of the 2/7. Instead of replacing the 3/1 on the seaward side of the Matanikau outpost, Thomas directed Hanneken to form a south-facing line to cover the left flank of the 3/7. The battalion was in position by dusk.

Around 2130, Briggs and his OP unit reached the jeep road bordering the Bowling Alley. There they observed an enemy battalion silently moving down the track toward the 1/7. Briggs ordered the platoon members to break into smaller groups and make their own way back to friendly lines. By that time the rainstorm had passed and bright moonlight filtered down through openings in the jungle canopy. Occasional cloudbursts continued, however, throughout the night.

The first of the Japanese units reached the American perimeter around 2200. This outfit (probably the one that had passed Briggs) attacked from the vicinity of the jeep road toward the junction of the 7th Marines and 164th Infantry sectors. The Japanese poured forth from the shadows at the edge of the jungle, running headlong toward the double-apron barbed wire and the muzzles of American guns. The defenders opened up with everything they had and called down mortar and artillery barrages. The division devoted two battalions of howitzers (a normal supporting complement for two infantry regiments) to answer the repeated calls from forward observers working with the 1/7. The adjoining units of the 164th added the weight of their mortars and machine guns against the enemy flank. The bullets and shells did their usual deadly work, but the 37mm guns added an extra dimension. Their crews employed canister rounds–essentially huge shotgun shells spraying small steel balls, designed specifically to deal with massed infantry in the open. More than one Marine was awed by the devastation wrought by these cannons. One recalled, ‘It really blows the living hell out of everything around.’ The courageous but foolhardy Japanese charge simply dissolved in the face of this overwhelming firepower.

The sudden, unanticipated threat to the southern perimeter worried Marine leaders. Puller’s men had fended off one thrust, but there were almost certain to be more before the night was over. The lines of the 1/7 were spread thin, and the battalion had no reserve, so there was a real chance the Japanese might punch a hole in the defenses. Any sizable enemy force breaking into the rear areas could quickly shut down the artillery and air power that were the linchpins of American strength. The division command post was still distracted by the ongoing battle at the Matanikau, but it nevertheless took immediate action to deal with the situation. As a first step, Thomas ordered the 164th’s 2nd Battalion to provide its local reserves to the 1/7. Soon after, three platoons of E and G companies were moving along the communication trail that led to Puller’s zone. When the Army units reached Captain Fuller’s rear area, he promptly brought them into his lines, where they occupied empty fighting positions or replaced casualties in Marine-manned bunkers.

Puller was glad to have the extra firepower of these soldiers, but he knew he needed many more men to hold the battalion’s long line. Around 2300, Chesty got on the phone to Frisbie and requested additional reinforcements. A little before midnight, Thomas agreed to up the ante and Lt. Col. Merrill Twining (the division operations officer) directed the 164th to dispatch its reserve battalion to reinforce the 1/7. Lieutenant Colonel Robert K. Hall left for the front immediately. His 3rd Battalion formed up in its bivouac site near Henderson Field and was headed south by 0200. The recent arrivals on the island did not know exactly where to go, but Frisbie, Puller and their staffs already had worked out that problem. The regiment’s Catholic chaplain, Father Matthew Keough, had been to the perimeter on numerous occasions. He guided the soldiers up to Edson’s Ridge and then onto the communications trail. As the long column moved along that path, Marines came back from the front lines–and each led an Army platoon through the last hundred yards of jungle. In the same fashion as the first wave of reinforcements from the 2/164, the men of the 3rd Battalion filled the empty bunkers and fighting holes. The process was largely complete by 0330. The additional men made an audible difference; all along the line, one participant recalled, the sound and tempo of firing picked up tremendously.

The Japanese had been busy with their own maneuvering. The second significant assault of the night came about a half hour after midnight, when lead elements of a battalion of the 29th Infantry reached the edge of the cleared zone directly in front of Able Company. The first company crawled across the open space and began to cut through the barbed wire. This stealthy attempt failed when a few soldiers recklessly revealed themselves before the breach was complete. The combined Marine-Army force blazed away again with all available weapons and slaughtered the exposed unit in less than half an hour. Subsequent assaults were made with equal bravery but much less skill or tactical thought. There was little or no attempt by Japanese commanders to coordinate efforts; most units attacked as soon as they came to the cleared zone that marked the Marine lines. The Japanese also failed to bring much supporting firepower to bear. Very few rounds were fired from Sendai mountain guns and mortars, and machine guns were seldom employed to duel with their American counterparts. One 29th Infantry company launched a typical charge against the 1/7’s Charlie Company at 0115. The Japanese infantrymen rushed forward, aided only by their own shouts of ‘Banzai!’ and ‘Blood for the Emperor!’ Within the space of a few minutes, all were dead or dying in front of the double-apron fence. Kelly later remarked, ‘It could not have been a more ideal situation from the defense standpoint.’

Puller and his staff counted six major assaults on their lines by 0330. So far the Marines and soldiers had held, but the continuous attacks were taking their toll. Ammunition was running low, and weapons were wearing out. Sergeant John Basilone, leader of two sections of heavy machine guns in the Charlie Company zone, performed magnificently in keeping his weapons operating. When a pair of guns was knocked out of action, he brought up a replacement for the surviving crew members, repaired the other one and then operated it himself until additional men arrived on the scene. In the midst of enemy attacks, he moved along the line doling out fresh belts of ammunition. The high rates of fire boiled away the water in the cooling jackets of the guns, and Basilone told his men to urinate in them to keep them going. Not far to the rear, mortarmen were using brief lulls in the action to dig out and resite tubes pounded down into the rain-soaked soil by the recoil of nearly continuous firing.

Through it all, Puller remained calm. For most of the night, he and a very small group of staff officers and enlisted men worked by flashlight in the command bunker while Japanese rounds pierced the jungle above. They supervised the flow of reinforcements and ammunition up to the front and kept Frisbie and Division abreast of the action. When the 3rd Battalion arrived on the scene, Chesty went out to the communications trail to greet Hall and bring him into the command post. The two lieutenant colonels conferred briefly and agreed that Puller should continue running the show, since he already had a handle on the situation. More than once the Marine commander’s bulldog attitude steadied his hard-pressed men. At one point Regan Fuller called back to the command post with the news that he was running low on ammunition. Chesty replied in his typically brusque, devil-may-care manner, ‘You’ve got bayonets, haven’t you?’ Puller knew ‘there was no such thing as falling back.’ His troops were in the best possible defensive positions, and there was not much ground to give in any case before the enemy reached the vital airfield. A Marine on Frisbie’s staff voiced the opinion of many in the perimeter that night: ‘Christ, I’m glad Colonel Puller is there!’ Twining later would say, ‘Puller’s presence alone represented the equivalent of two battalions.’

The final Japanese assaults of the night came just around dawn. Colonel Masajiro Furimiya, commander of the 29th Infantry, led one attack, accompanied by the regimental colors and the company charged with guarding them. In the last minutes of darkness, he led his small force across the open ground and through the battered wire. The defenders were tired, short of ammunition and distracted by a large simultaneous thrust just to the west. Casualties also had thinned the line. The Americans exacted a toll, but Furimiya and about 60 of his men made it past the bunkers and into the jungle behind the line. It was the only significant penetration of the night. It also proved futile, since the Japanese had not stopped to destroy the defenders’ fighting positions and thus create a hole for follow-on forces to exploit. Instead, the colonel’s force constituted a small pocket in the American rear. Another attack just after sunrise failed miserably. In addition to Furimiya’s enclave, a few dozen other Japanese soldiers had infiltrated in ones and twos. Maruyama wisely called off further attempts and pulled back his forces. The Sendai would try again that night.

Daylight on October 25 brought clear skies above and revealed a scene of utter carnage on the ground. Hundreds of bodies carpeted the narrow cleared strip fronting the eastern half of Puller’s sector. In a few spots the corpses were stacked two and three deep. Near Company A’s left flank, the dead lay in windrows, scythed down by 37mm canister rounds as their formations had moved along the jeep road and emerged from the Bowling Alley. The debris of war was everywhere: broken weapons, ripped-open ammunition containers, lost equipment, dirty bandages, bits of uniforms and lengths of broken barbed wire. In the midst of that charnel house, American officers and NCOs automatically began the process of reorganizing their men, resupplying ammunition and responding to occasional small-arms fire from Japanese stragglers in front of and behind the lines. Marines and soldiers moved in on Furimiya’s small force and squeezed it out of existence, killing 52 enemy troops in the process. American infantrymen accounted for an additional 43 enemy scattered about the perimeter.

Chesty walked his lines and conservatively estimated there were more than 300 dead in the fire lanes, plus hundreds more inside the jungle beyond the cleared ground. The Americans had decisively won the first round, but Puller dispatched a hastily scrawled report that gave no cause for immediate celebration. He was certain the enemy had a strong reserve and was ready to use it: ‘Believe Japanese will assault with large forces tonight.’ Chesty was still trying to determine the extent of his losses, but knew he had more than the one dead and 12 wounded already counted. There was one bit of positive news. Early in the afternoon, men in Company A’s zone observed the Japanese shooting at someone in the kunai grass of the Bowling Alley. Seeing that the targets were survivors of the OP, Regan Fuller ordered his men to provide covering fire while he drove a jeep out to get them. A mad dash left the vehicle riddled with bullet holes, but he brought in a few of the Marines. Soldiers from the 164th duplicated that feat with a weapons carrier and rescued the remainder of the group. Much of the platoon was still missing, but it seemed a miracle that anyone had made it through the Japanese encirclement.

Briggs was one of those who had run the gantlet. Chesty called for him and asked for details about the enemy. The platoon sergeant recounted as much as he could and noted that the battalion commander ‘digested [it] calmly, as though he was sitting in his tent in New River, instead of in the mud and blood.’ Puller already was focused on preparations for the coming night. With most of the Japanese infiltrators liquidated, he and Hall were beginning to sort out their forces. They decided that the Army battalion would take over the left half of the sector, while the 1/7 consolidated astride Edson’s Ridge.

It was a trying time for everyone on Guadalcanal. The Cactus Air Force struggled all day to get planes off the ground from shell-pocked Henderson and the muddy fighter strip. Enemy air attacks were heavier and more frequent than usual, and Imperial Japanese Navy destroyers put in a rare daylight appearance off Lunga Point. American and Japanese artillery also traded fire. Both sides drew blood in the air, at sea and on land during the course of what would come to be called ‘Dugout Sunday.’ The Japanese directed most of their effort against the airfields, but a few planes bombed and strafed the perimeter defenses, and the 150mm guns lobbed shells in that direction.

While the fighting raged elsewhere, the Sendai Division regrouped in the jungle and prepared for its second attempt. The much-depleted 29th Infantry again would serve as the spearhead, despite having its 3rd Battalion practically annihilated the previous night. In recognition of that regiment’s losses, the 16th Infantry would reinforce the effort. The 230th was destined to miss the fight a second night in a row. The regimental commander feared a flanking counterattack by the Americans, so he deployed his force in a defensive posture facing toward the east. The Japanese were attempting to rectify some of their errors. This time Lt. Col. Watanabe, commander of Furimiya’s 2nd Battalion, reconnoitered the front himself prior to leading the renewed assault. And the Sendai mustered its few mountain guns and mortars for a preparatory bombardment of the American lines.

The American reorganization of the southern sector was complete by evening, and the defenders girded themselves for another rough night. They did not have long to wait. The Sendai Division fired its limited supply of shells in a weak barrage beginning at 2000. Then Japanese infantrymen surged out of the jungle in an attempt to cross the few dozen yards of deadly open ground in front of the American lines. Their focus seemed to be the point where the jeep road from the Bowling Alley entered the perimeter. The assaults lasted all night long, but none came against the 1/7’s positions. Puller’s battalion was on the receiving end of only a handful of shells and some minor sniper activity. The 164th Infantry, with the assistance of elements of the 7th Marines Weapons Company, repulsed every attack and inflicted hundreds of fresh casualties on the Japanese. The inland wing of the diversionary force finally launched its attack against the line occupied by Hanneken’s outfit. That enemy effort fared no better than the others.

Maruyama admitted defeat the next day, October 26, but some survivors of the Sendai continued the action that night. The 164th repulsed several nighttime assaults, and a brief evening mortar barrage hit the left flank of the 1/7, killing five men. A few of these probes were attempts to reclaim the colors of the 29th Infantry, though given the state of Japanese communications, several units may not have received the order to withdraw. It would take time for the exhausted Japanese to disengage fully and begin the arduous return march to the sea, but the battle was over.

The Sendai Division’s losses were heavy. On October 27, the 164th began the gruesome job of supervising the burial of enemy corpses, many of them already decomposing after two days of tropical heat. The task was so large that bulldozers and dynamite were employed to assist the Japanese prisoners assigned to the job. Among the dead were a general and two regimental commanders. By the time the burials were finished, the 164th had counted more than 1,075 bodies in and around the lines and estimated there were another 1,500 scattered through the jungle beyond. The Japanese 29th and 16th Infantry regiments were no longer effective fighting organizations. Casualties for the second diversionary force likely exceeded 1,000.

American losses were significant, but they paled in comparison to those of the enemy. The 164th Infantry counted 29 dead and 70 wounded. The units on the Matanikau had suffered 16 killed and 43 wounded, most of them in the 2/7. Puller initially informed division command that his battalion lost 19 dead, 30 wounded and 12 missing. Deaths from wounds and the eventual return of others from the platoon outpost brought the final totals to 24 dead, 28 wounded and two missing. Chesty closed his official report on the battle with the observation that his outfit’s casualties on Guadalcanal now totaled 24 percent.

Several factors accounted for the lopsided victory. The strong perimeter fortifications proved critical, since they significantly reduced friendly losses and helped the 1/7’s thin lines hold on during the night of October 24. A sergeant in the 164th felt that the barbed wire ‘must be given a great deal of credit for slowing and confusing the Japanese.’ The nature of casualties in the 1/7 also attested to the abundance of overhead cover in the American fighting positions–and the paucity of Japanese indirect fire. In a remarkable deviation from the norm, shrapnel accounted for only two of the 28 wounded; the rest were all gunfire casualties. A Japanese company commander in the 29th Infantry credited the ‘intense machine gun and mortar fire’ and noted that the Marines ‘had excellent detectors set up which discovered our movements.’ Another captured enemy document stressed the ‘cooperative firing’ of the Americans, who ‘never fight without artillery.’ Puller himself implied in an October 28 note that mortars and howitzers had inflicted most of the casualties. Years later, he would state, ‘We held them because we were well dug in, a whole regiment of artillery was backing us up, and there was plenty of barbed wire.’ A staff officer from the Japanese theater headquarters laid the greatest blame on ‘poor command and leadership.’ He also emphasized the middling quality of his own forces: ‘The [Sendai] Division had little hard combat experience, as it had engaged only in the easy Java campaign. Though high-spirited, they were not expert fighters. The [29th Infantry] knew nothing but bayonet charges.’ Surprisingly, one Japanese officer thought the Americans lacked initiative, but admitted ‘they do more duty than they are told.’ Advantages in firepower and field fortifications notwithstanding, the Marines and soldiers had done much more than their duty. And they had been well trained and well led by men like Puller, Basilone and Hall.

Although the 164th had borne the brunt of the fighting during the last two days of the battle, the 1/7 had stood alone during much of the crucial first night and barred the way when American defenses were thinnest. Puller was proud of his battalion’s performance, but he gladly credited the Army’s assistance. Considering that the inexperienced reinforcements had been thrown into a confusing situation in the middle of the night, he thought the conduct of the soldiers had been ‘exemplary.’ He also believed they had arrived just in time, and he told reporters a few days later, ‘I was damned glad to see them.’ Marines and Army men fighting side by side had deflected the enemy’s strongest blow. There were months of hard fighting ahead, but never again would there be serious doubt about the outcome on Guadalcanal.

This article was written by Jon T. Hoffman and originally appeared in the November 2002 issue of World War II. For more great articles subscribe to World War II magazine today!